According to a new study, grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem may someday bridge the gap separating them from Yellowstone grizzly bears.

In a forthcoming study in Ecosphere, the Ecological Society of America’s open access journal, grizzly scientists analyzed recent trends in grizzly movements and looked at ways these two “islands” of bears could someday reunite.

Indeed, according to Phys.org, that reunion may already be in works, however tentatively. This summer, biologists with the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks agency spotted a grizzly in the Big Belt Mountains outside Helena, Montana—a sign that some grizzlies may be leaving their enclaves. We previously reported that Yellowstone grizzly bears are also venturing out of the park more and more. From Phys.org:

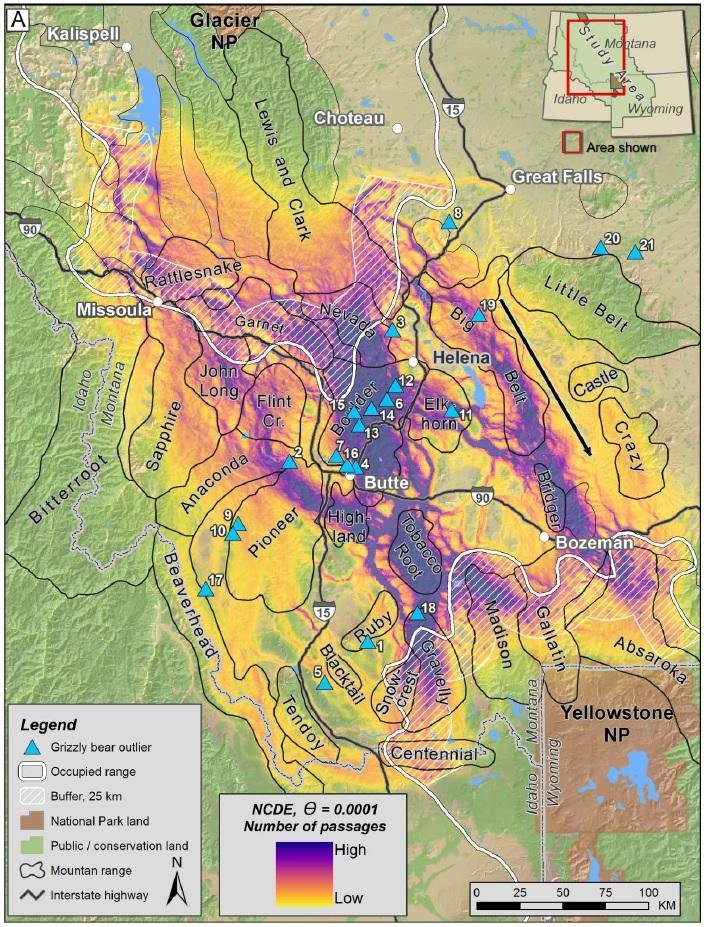

Drawing from rich data on the movements of male bears in both grizzly populations, the researchers projected the rambles that future bears might take to pass through (or bypass) human occupied territory around Helena, Butte, and Bozeman, hopping between islands of wildlands in developed farm and rangeland. The bears’ best options may be the longest routes, the researchers say, traversing state and federally owned wildlands in a westward arc around the more developed Interstate 90 corridor.

“We let the male bears tell us where they would be most likely to go, by looking at their movement characteristics. We had the luxury of huge datasets of location data from both populations. We could be very picky about our data selection,” said Frank van Manen, team leader for the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team. He coauthored the study with seven colleagues from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Wyoming Game and Fish, and his own home agency, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

Increasing public interest in a reunion of the Yellowstone and Northern Continental bear families motivated van Manen and colleagues to look at the possible paths the bears might take. An influx of genetic diversity through breeding with outsiders could give the Yellowstone grizzly population greater resiliency to changing environmental conditions.

“We’ve been asked for this information by many groups invested in grizzlies. Organizations involved in land conservation want to know where land purchases will be most useful. Government agencies need to know where to put in place education efforts,” said coauthor Cecily Costello, a research wildlife biologist at Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks in Kalispell.

Places like Yellowstone National Park and the Northern Continental Divide (which encompasses portions of Glacier National Park, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, the Flathead and Blackfeet Reservations and several other national forests and wilderness areas) are considered “islands” for grizzly bears and other species because they are effectively isolated from the surrounding landscape. Bears leaving Yellowstone National Park or the Divide effectively enter “human” space, where the rules for bear survival are wholly different from the rules in these biogeographical islands.

Consider, for instance, that Yellowstone grizzlies were taken off the Endangered Species List this summer. Although that change does not affect their status inside Yellowstone, it does affect their movement outside park boundaries. Indeed, the state wildlife agencies in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho have all mulled the possibility of conducting trophy hunts, which could deter grizzlies from reconnecting with their fellow bears to the north.

Further, even if the specter of trophy hunting didn’t loom over grizzlies, they would still face special challenges in leaving “their” territory. That’s why researchers place emphasis on establishing “connectivity” between these populations. Part of the forthcoming study looked at charting possible movement paths for grizzlies, seen in the map above. From Phys.org:

Establishing a natural genetic exchange between the populations, without resort to relocation of animals, is a top priority for many people invested in the recovery of grizzly bears, and a long-term management goal for the state of Montana.

But expansion will take the bears onto private land, and lead to encounters with dangerous highways. With more human dominated landscapes comes the potential for conflicts with people.

“The dispersing males, they are the ones that get in trouble, that get into the garbage, that roam into town, because they are more exploratory,” van Manen said.

Preparing people to coexist with bears may be as important as securing conservation easements, said van Manen and Costello. Bear-proof garbage storage systems and electric fences around beehives can minimize conflicts with people and go a long way towards securing a safe path for the bears. Costello would like to look at potential highway crossings, to investigate ways to mitigate collisions with vehicles. But she emphasizes that the models represent movement corridors. The projected paths, particularly where they cross more developed low country, do not necessarily indicate where bears would set up permanent residence.

In spite of these obstacles, van Manen believes we are “within the realm of immigration events happening naturally.”

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.