One of the largest thermal basins in Yellowstone National Park, Norris Geyser Basin is also one of the most volatile.

And not just in a geological sense, either, according to the 1898 Haynes Guide:

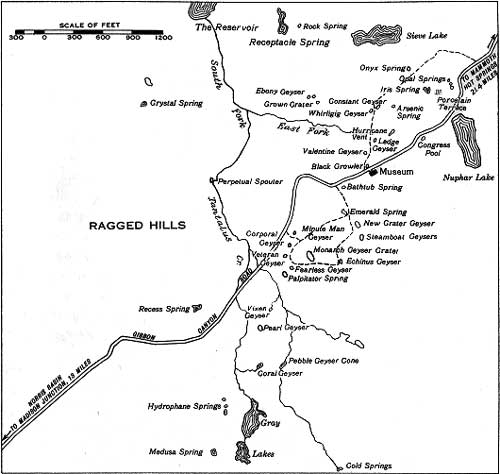

This region, called the Gibbon Geyser Basin in Dr. Hayden’s report, was discovered in 1875 by Col. [Philetus] W. Norris, then superintendent of the Park. Since 1881 it has been called Norris Geyser Basin, which name it is quite likely to retain. It covers an area of six square miles, and is one of the most interesting portions of the Park from a geological standpoint from the fact of its being one of the highest geyser basins in the Park, and many of its active geysers being of quite recent origin (29, 31).

That assessment of Norris holds true today, since many of its features have undergone marked changes. Indeed, the treatment of Norris over the last hundred-plus years has continually. As recently as 1953, the Park road ran through the basin, which is not the case today, due to new found understanding of the fragility of Yellowstone’s thermal features. Norris used to be a popular stopping place for visitors to walk the basin and grab lunch before heading down to Old Faithful or the old Firehole Hotel.

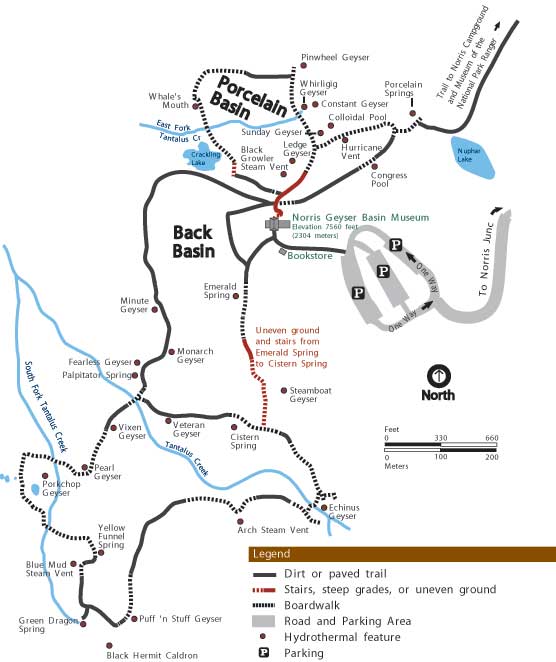

Today, navigating Norris is a little tricky since 1) the boardwalks and dirt paths slope with the landscape and 2) it’s split into two large basins: Porcelain and Back. Each offers their own attractions, surprises and curiosities. Of the two, Porcelain is the smaller, although it has some of the more difficult walking in Norris. If you’ve got small children that you wish to take down to Porcelain, leave the stroller behind.

Looking out from the museum, Porcelain spreads like patchwork quilt of natural hues: sulfur-yellow, iron oxide orange, calcified white, sky blue and algae-green. Most of the features are concentrated toward the bottom of the slope. None of the geysers in Porcelain are particularly regular. However, many of the other features (hot springs, fumaroles, vents) are impressive in their own right and colorfully named. Whale’s Mouth, for instance, lives up to its gargantuan namesake. And Black Growler Steam Vent imprints its name upon visitors’ minds: a plume of steam rising from a seemingly scorched hillside.

Whereas Porcelain Basin is relatively compact and open, Back Basin sprawls through forest and over creeks. Much like Porcelain, the Back Basin is largely inactive, eruption wise. It is, however, brimming with potential energy. For instance, Back Basin is home to Echinus Geyser, a former frequent erupting feature that has gone all but dormant since its decline in the late ’90s. Named after the biological genus (Echinus encompasses certain sea urchins) Echinus does indeed resemble sea urchins in appearance and human urchins in disposition. Curiously, Echinus is also the most acidic geyser in the Park, with a pH of roughly 3—the same pH as vinegar.

Back Basin is home to Steamboat Geyser, the tallest in the world. Its eruptions can exceed 300 feet. Alas, it is wholly unpredictable; Steamboat has been known to lay dormant for years before suddenly springing to life again. Of course, even when it isn’t erupting, Steamboat’s complex of vents and pools is impressive.

That line of thinking goes for Norris Basin as a whole, especially the Back portion. Besides geysers, Back is home to several gorgeous hot springs. Emerald Spring is that exact lovely clear shade of green and gives visitors a great first impression of the Back Basin. Green Dragon Spring, on the other hand, is a hidden attraction: a small pool partially covered by yellow rock, obscured (most of the time, except on warm sunny days) by steam furling from the earth.

One of Back’s other appeals for visitors is the large portion of features that are (as of yet) unnamed. Nameless milky white pools stretch across the landscape, waiting for an intrepid imagination to name them. It’s a testimony to Norris Basin’s volatility. In terms of geologic time, Norris changes often, sometimes violently; Porkchop Geyser (named for its shape) was a roaring spouter before its sudden explosion on September 5, 1989, which strew rocks and debris over 200 feet away from the vent.

Besides the thermal features, Norris Basin also offers wonderful views of the surrounding mountains and gets you up and close to swaths of lodgepole saplings born in the aftermath of the 1988 Yellowstone Fire. Just think: someday, parts of the Back Basin boardwalk will be ensconced in a thick stand of lodgepoles: a powerful attestation to Yellowstone’s dynamism.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.