June 27, 1938: novelist Thomas Wolfe stood with arms akimbo watching Old Faithful erupt. Three months later, he was dead.

The two incidents aren’t literally linked, but they stand in immense contrast to each other. Indeed, Wolfe stood before Old Faithful as a man in transition, a man looking to make a huge change in his life, and who found himself reenergized by not only Yellowstone National Park but the West as a whole.

A Wolfe Primer

By the time of his death September 15, 1938, Wolfe was one of most famous American authors, simultaneously hailed and derided for his voluminous novels. Often autobiographical, the books were nonetheless shot through with arresting, original phrasing and intense emotionality.

Born October 3, 1900 in Asheville, North Carolina, Wolfe spent most of his life in NC before venturing into the world, first to New York, then beyond.

Among his contemporaries, he was hailed as a talent, who had the potential for greatness, especially on the promise of his debut novel; Look Homeward, Angel. Although titans like William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway rescinded or tempered their early praise, a host of younger followers (Ray Bradbury, Betty Smith, Hunter S. Thompson, Pat Conroy) all professed their love and admitted Wolfe’s influence.

“Who’s Thomas Wolfe?”

According to the Virginia Quarterly Review (VQR), the spring of 1938 was a momentous time in Wolfe’s life. He had just broken with Charles Scribner’s Sons, the publishing house of Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and (in particular) his editor Maxwell Perkins. In several reviews, Perkins had been held up as the real architect of Wolfe’s work. Without Perkins, Wolfe’s books would have been unreadable, indigestible anima, one reviewer said.

After breaking with Scribner’s and Perkins, Wolfe decided to travel to Portland, Oregon to visit family. He also planned a speaking engagement at Purdue University. After that, he had no immediate plans. In leaving New York, he also left behind two immense manuscripts—what would eventually be published as The Web and the Rock (in 1939) and You Can’t Go Home Again (in 1940).

Before Wolfe entered the scene, Raymond Conway of the Oregon State Motor Association had contacted Edward Miller (Sunday editor of the Portland Oregonian newspaper) and pitched a story about traveling the West by automobile, which would demonstrate how cheaply a motorist could see “the Western national parks within the time limits of the average man’s vacation.” Miller and Conway had done similar trips, and agreed to it, when a senior Oregonian editor suggested they take Wolfe with on their trip. In response to the suggestion of his senior editor, Miller reportedly blurted “Who’s Thomas Wolfe?”

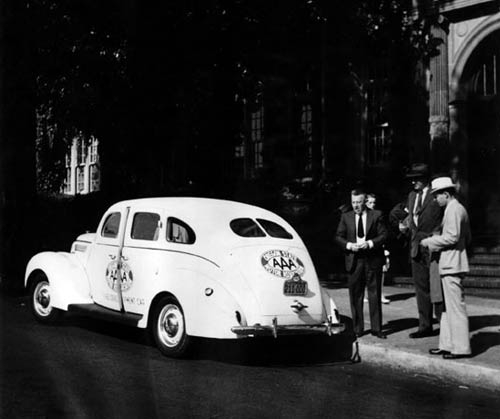

In short time, however, Miller and Conway came to know Wolfe, and subsequently invited him on the trip, which would be taken in a custom white “Travel Development Car,” pictured just below.

“I Shall Have Really Seen America (Except Texas)”

Throughout the trip, Wolfe wrote long, descriptive letters to his literary agent, Elizabeth Nowell (and who he refers, in his correspondance to, as “Miss Nowell”), keeping her abreast of his doings as they traversed the Western United States, betraying his excitement and anticipation about the trip as a whole. From a letter to Miss Nowell, by way of Thomas Wolfe: An Illustrated Biography, edited by Ted Mitchell:

The whole thing will take two weeks to the day—perhaps a day or two less for me, because I intend to leave [Miller] at Spokane, and head straight for N.Y.—I’ve seen wonderful things and met every kind of person—doctors, lawyers, lumberjacks, etc—and when I get through with this I’ll have a whole wad of glorious material—My conscience hurts me about this extra two weeks, but I believe I’d always regret it if I passed it up—when I get through I shall really have seen America (except Texas).

The trip itself was like something out of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road (incidentally, Kerouac was a huge fan of Wolfe)—methodically fast-paced, freely offering the writers involved innumerable glimpses into the lives of people spread across 11 states, as well a chance to get away from it all. From VQR:

In thirteen days, the trip passed through Crater Lake, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, Glacier, and a half-dozen other national parks. They covered more than 4,500 miles, Conway and Miller switching off at the wheel every hundred miles while Wolfe squeezed his six-foot-six-inch frame into the back seat. Despite the physical discomfort of being confined in the car, Wolfe was by all indications having the time of his life. Miller would later write

Tom told us that he had spent more time with the two of us—that is, steady-diet time—then with any any person or persons since he was in the teens. And when you keep company with any one for two weeks steady, you get to know them rather well. And between Conway and myself, Tom put in a good deal more time with me because we hit for the beer counters while Conway was sleeping or keeping his books.

Wolfe even left behind a proto-On The Road travelogue, which he called A Western Journal, which he worked at throughout the entire trip. In the Journal, during the Yellowstone trip, Wolfe notes how Conway’s apparent “unstinting watchfulness” during parts of the trip got on Wolfe’s nerves. Nonetheless, they seem to have parted on good terms.

First Day In Yellowstone (“Moving Through Hot Oatmeal”)

Wolfe and company arrived in Yellowstone by way of Idaho, driving up from Pocatello, which is just east of Craters, and just south of Idaho Falls. They drove into Jackson Hole (which Conway calls “almost a hole itself,” according to Wolfe; he meant it as a compliment) and admired the city of Jackson before heading north through Grand Teton National Park, everyone admiring “the vastness and the sweetness and the Tetons” all along the way.

The whole journal is shot through with Wolfe’s particular panache, of course, but once in Yellowstone, Wolfe’s literary sensibilities really kick into gear, driven in large part by the uniqueness of the geyser plains. Another sign that Wolfe precursed Kerouac : all of the Western Journal is arranged in dense paragraphs, every entry essentially one long run-on sentence broken up by dashes. Even when tamed by typeset and printer paper, Wolfe’s journal entries still profess a rushing, feverish mindset. From A Western Journal:

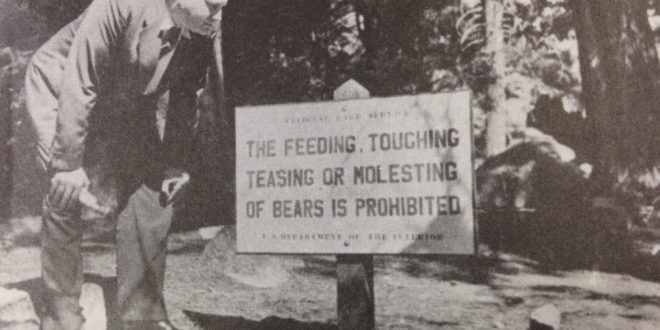

and the Park entrance, and the ride up through pine-hemlock etc trees and then the Snake River foaming in its canyon, then a lake with the thick forest round it then the “Thumb” of Yellowstone, the Paint Pots and the boiling waters, sinister, grotesque, curved like a rhinoceros imbedded moving through hot oatmeal—then by narrow road to Old Faithful and a bear by privy and the woods, and smoke boiling from the ground

From West Thumb the party made their way northwest to the Old Faithful Inn, where they had cabins through the Lodge. Most of June 27 was spent getting to Yellowstone and taking in the Old Faithful area. For instance, in the Journal, Wolfe is near-rapturous in describing an Old Faithful eruption, paying attention not only to the geyser but also the crowd. In the picture below, you can see Wolfe and a traveling companion (likely Conway, since Miller reportedly manned the box camera throughout the trip) watch Old Faithful perform:

and then the vast bouquet of Old Faithful, the enormous Inn, the tremendous lodges, the cabins—our run by the small fast flowing river—and the Crater lid, volcanic, the earth smoking from a hundred holes, and old Geyser and the people waiting, the hot boiling overslopping of the pot, and then the vast hot plume of steam and water—and the people watching—Middle-America watching—kids, old men, women, young men, women—all—and the hot plume, the tons of water falling and the hot plume dipping

After watching Old Faithful erupt, the trio ambled over to the Lodge to savor an “all-you-can-eat” meal for $1—which was hardly anything then even—keeping an eye on Old Faithful from the window of the dining hall.

True to Miller’s word, he and Wolfe parted ways with Conway (who went to his cabin—presumably to read) for the evening while they sidled up to the bar in the Old Faithful Inn, staying there the rest of the night practically. From Wolfe’s Western Journal:

and so goodnight to Ray—and then to dance and people dancing—so to the Great Inn to the bar—like liner shipboard bar—more merriment here and people more prosperous less cultivated and singing “We don’t give a damn for the whole state of Utah”—and so talking and drinking with M.—and present the bar closes—midnight—and the rain ceased—the night cleared to heaven and a billion stars and to our lodge and to our cabin—Ray away and talking all together—so to bed.

Last Day In Yellowstone (“I’ll Have a Parboiled Boy”)

Miller woke Wolfe at 8:40 a.m. Tuesday, June 28, 1938, ushering him (after quickly getting dressed) to the cafeteria for breakfast. From there the party made their way north to Biscuit Basin (where Wolfe admires Sapphire Pool and records a father telling his boy not to lean too much on the railings or he’d fall in. “I’ll have a parboiled boy,” the father tells his son).

From there, they made their way through the Lower Geyser Basin and up to Norris (not staying long) before cutting over to Canyon, where Wolfe waxes rhapsodic about the trees and the elk and a bear jam. They had lunch in Canyon Cafeteria, then made their way across the Melan Arch Bridge over the Yellowstone to see the canyon. From A Western Journal:

and so across the Bridge to see the mighty falls of Yellowstone and water falling boiling and the rushing current of the Canyons loveliest stream—so clear and bright and pure compared to Colorado—so photographs and Ranger posing (for himself perhaps) with opera glasses the steep wooded depths, the somewhat yellow walls (hence Yellowstone)

Wolfe notes (with disappointment) that they didn’t have time to stop at the Canyon bear feeding area.

From Canyon they head north and west toward the “enchanted mountain country” around Mammoth Hot Springs. All in all, Wolfe seems unimpressed with the terraces, calling them “bleak and disappointing.” Perhaps however, he merely felt wistful about leaving the Park, especially as they pass through the Roosevelt Arch (after taking a picture with it, and after Wolfe mistakenly says it was built in 1872).

From Gardiner, Wolfe and company roll north, with Wolfe reveling in “the miracle of evening light and the celebrated river called the Yellowstone and trees most green and marvellous” as they roll toward “the lights of Bozeman.”

Aftermath

At the end of their trip, Miller and Conway deposited Wolfe in Olympia, Washington. The ending of the trip was more than a little bittersweet for Wolfe, as he notes toward the end of his journal:

and they are gone, and a curiously hollow feeling in me as I stand there in the streets of Olympia and watch the white Ford flash away—

As much as bittersweetness and Weltschmerz, however, Wolfe is also left with a definite appreciation and (in this writer’s opinion) apprehension of the nation:

the pity, terror, strangeness, and magnificence of it all.

In another letter to Miss Nowell (postmarked July 3, 1938, from the New Washington Hotel in Seattle), he puts it a little more cheerfully:

The trip was wonderful and terrific—in the last two weeks I have traveled 5,000 miles, gone the whole length of the of the coast from Seattle almost to the Mexican border, inland a thousand miles and northward to the Canadian border. The national parks, of course, are stupendous, but what was to me far more valuable were the towns, the things, the people I saw—the whole West and all its history unrolling at kaleidoscopic speed.

Alas, outside of A Western Journal, Wolfe would not make anything of the trip. In Seattle, he came down with pneumonia, spending most of July hospitalized. He eventually contracted military tuberculosis of the brain, and was sent to John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

One of the last things Wolfe ever did, before dying, was write a letter of apology to Perkins, who he viewed as his closest friend.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.