David Quammen is, rightly, one of the most lauded science writers of the past 30 years.

Author of such works as The Song of the Dodo, The Boilerplate Rhino, and Spillover (which, since part of the book discussed Ebola, made him a very visible commentator during the fall of 2014), Quammen is renowned as a world traveler, writing on nature, science, and wilderness, among other topics. His books limn the boundary between wilderness and civilization, often highlighting just how thin that line really is, truth be told.

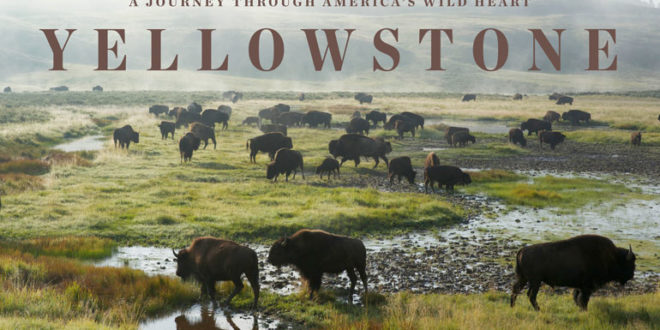

Certainly, locating that boundary is one of many topics Quammen explores in his new book Yellowstone: A Journey Through America’s Wild Heart. Adapted from a special issue Quammen wrote for National Geographic to commemorate the National Park Service’s Centennial, Yellowstone intimately considers the Park as both a slice of seemingly timeless landscape and as a place still being shaped today.

In Yellowstone, Quammen is joined by Todd Wilkinson (who contributed all the captions and sidebars) as well as a host of talented photographers (Michael Nichols, Charlie Hamilton James, David Guttenfelder, Joe Riis, Erika Larsen, Ronan Donovan, Drew Rush, Cory Richard, and Louise Johns). To say nothing of the older, archival photographs peppered throughout the book as well as maps from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Quammen may have written the core text, but without these contributions, Yellowstone wouldn’t have the same heft. Speaking figuratively, of course, because the book itself is light, easy to hold, props open well on a table or in your lap. The real heft comes from the interaction between Quammen’s words and the vast array of pictures at his disposal.

In tone, Yellowstone is vintage Quammen: learned without being obtuse, serious rumination paired with moments of levity. He covers all corners of the Park, from Yellowstone’s thermal treasures to the pressing issues of tourism and climate change. In this regard, Yellowstone covers territory seldom seen by the average boardwalker.

Indeed, readers looking for more geyser gushing may be disappointed, as Quammen goes more for the Park’s animal population, especially the grizzly bear and wolf. Quammen’s conception of Yellowstone is as a wildlife reserve of the first order—the wild heart of the country, so to speak—whose transformation into such was wholly unexpected but fortuitous.

Quammen’s other concern in Yellowstone is understanding what it means for a landscape to be, on the one hand, a repository for some of North America’s most beloved and most threatened animals, and on the other, a stomping ground for millions of people—in his famous essay, “Planet of Weeds,” Quammen described homo sapiens “the consummate weed,” able to flourish wherever, often to the detriment of what’s there already.

In Yellowstone, Quammen calls this situation (Yellowstone as wilderness vs. Yellowstone as wonderland) “the paradox of the cultivated wild.” Indeed, it’s how Quammen introduces the Park (using that phrase as the title of his first chapter) and it’s how Quammen keys readers into the issues facing the Park.

Wallace Stegner famously called the national park system “America’s best idea,” which filmmaker Ken Burns later used as the title to his national park series. Quammen isn’t so sure he agrees—half joking, half opining, he says the Declaration of Independence was a pretty swell idea too—but he never denies that “the national park” is an important idea. And Yellowstone is its first, and best, manifestation:

Now we have many national parks, of many sorts and sizes, spread from Kobuk Valley in Alaska to Everglades in Florida, and from Haleakala in Hawaii to Acadia in Maine. Yellowstone is still special. The story of Yellowstone National Park plus its adjacent lands—and the adjacent lands must be part of the story—shows us that this “best” idea had mixed origins and that it has always been a work in progress, initially vague, unforeseeably complex, continually evolving, more contentious today than ever.

Yet it is a great idea, the idea of national parks, and Yellowstone will remain its greatest embodiment, not just for American but also for the world, if we can only agree what we want the place to be, and to do, and to mean.

Throughout Yellowstone, Quammen serves as an amiable, stalwart steward, conveying readers through Yellowstone National Park with consummate ease and composure. You’d do well to pick up a copy.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.