Somewhat off the beaten (or shall we say paved) track in Yellowstone National Park, Apollinaris Spring has an illustrious history with the park.

Indeed, in terms of attractions, Apollinaris has had remarkable staying power, on par with some of the more famous geysers. It flows more regularly, in any case.

But Apollinaris is as much a product of Yellowstone history as it is a natural feature—to the extent it can be called “natural.”

Name Origin

According to the National Park Service, Yellowstone’s Apollinaris Spring reminded the (often wealthy) visitors of a German mineral spring also named Apollinaris, after Apollinaris of Ravenna, a patron saint of gout, among other things.

The water was famed in Europe for its taste. Indeed, in the late 19th century (around when visitor started flocking to Yellowstone National Park), the water had the imprimatur of a drinker’s sophistication. Imbibers of the German drink are referenced in William Dean Howells’ The Rise of Silas Lapham, Arthur C. Doyle’s The Lost World, “Counterparts” by James Joyce, and several O. Henry stories.

Apollinaris, incidentally, is an ancient name, dating back thousands of years. Some famous holders of the name include a correspondent with Roman magistrate Pliny the Younger (nephew of Pliny the Elder, author of Naturalis Historia, one of the earliest encyclopedias), a first century astrologer, and Apollinaris of Laodicea, a fourth century Syrian bishop who promulgated the belief that Jesus Christ had a mortal body but a divine mind—a system that became known as Apollinarism and was later declared a heresy by the First Council of Constantinople (381 A.D.)

A Gathering Place

As mentioned, Apollinaris Spring was quite popular with the stagecoach crowd, who liked filling bottles and canteens with the stuff as they ventured south toward the basins. Although popular with the tourists, the stagecoach drivers rarely got to join in. According to Aubrey L. Haines, writing in Volume Two of The Yellowstone Story, drivers slaked their thirst differently:

The stagecoaches stopped at Apollinaris Spring to enable the passengers to stretch their legs and drink the water so like that from the namesake spring in Germany. Almost everyone was thirsty—at times, even the driver (depending upon where he had been the night before and how much he had been “geising” to his dudes); but, since a driver was not allowed to leave his rig, and seldom liked spring water anyhow, he had to find another way to slake his thirst. An old surrey driver (Doc Wilson) would roll souvenir bottles of “Old Yellowstone” whiskey (then fifteen cents each) in the side curtains of his vehicle for use in such an emergency. On one trip, he was taking a nip from that hiding place when a lady tourist, who had not walked up to the spring, stepped around the rig and caught him at it. He later confided to another driver, “Herb, I was so embarrassed!”

The spring was more than a stagecoach stop, however. In the early days of the Wylie Camping Company, it was the site of a popular permanent camp. Indeed, as business grew and more visitors took to “the Wylie Way,” the company still maintained a camp in the area—just south in Swan Lake Flats.

The 1920s

With the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 and the arrival of the automobile, the touring dynamic of Yellowstone changed. Increasingly vestigial, the stagecoach culture faded more and more and is by-and-large gone from the park now.

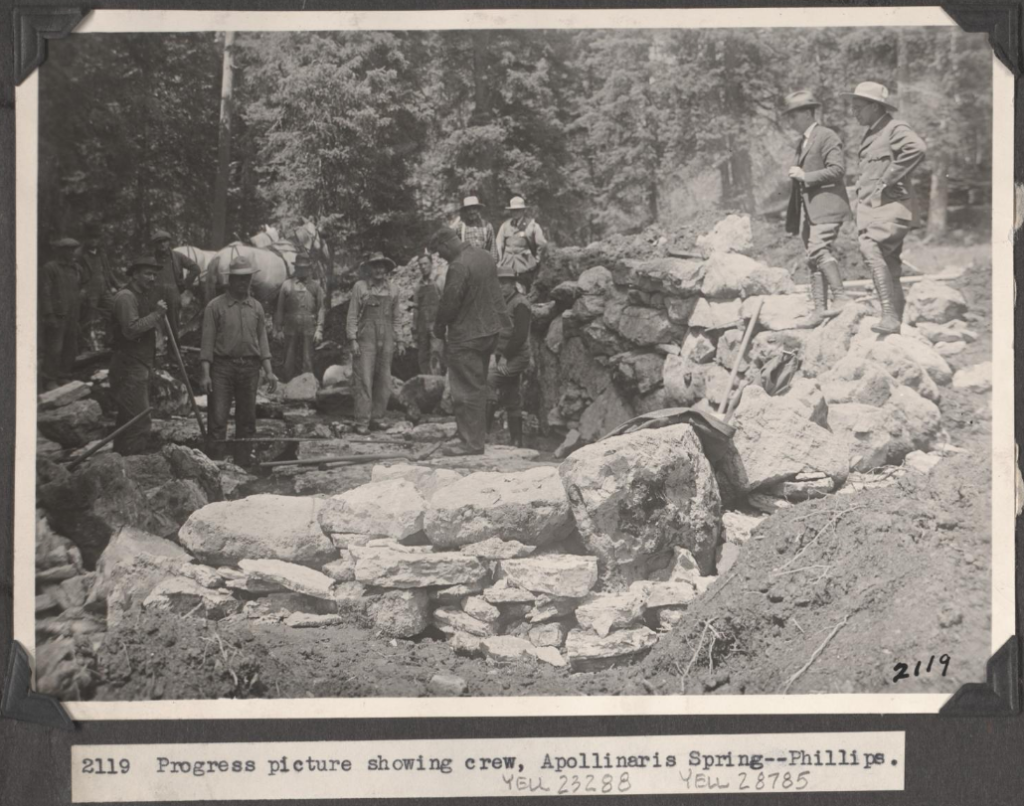

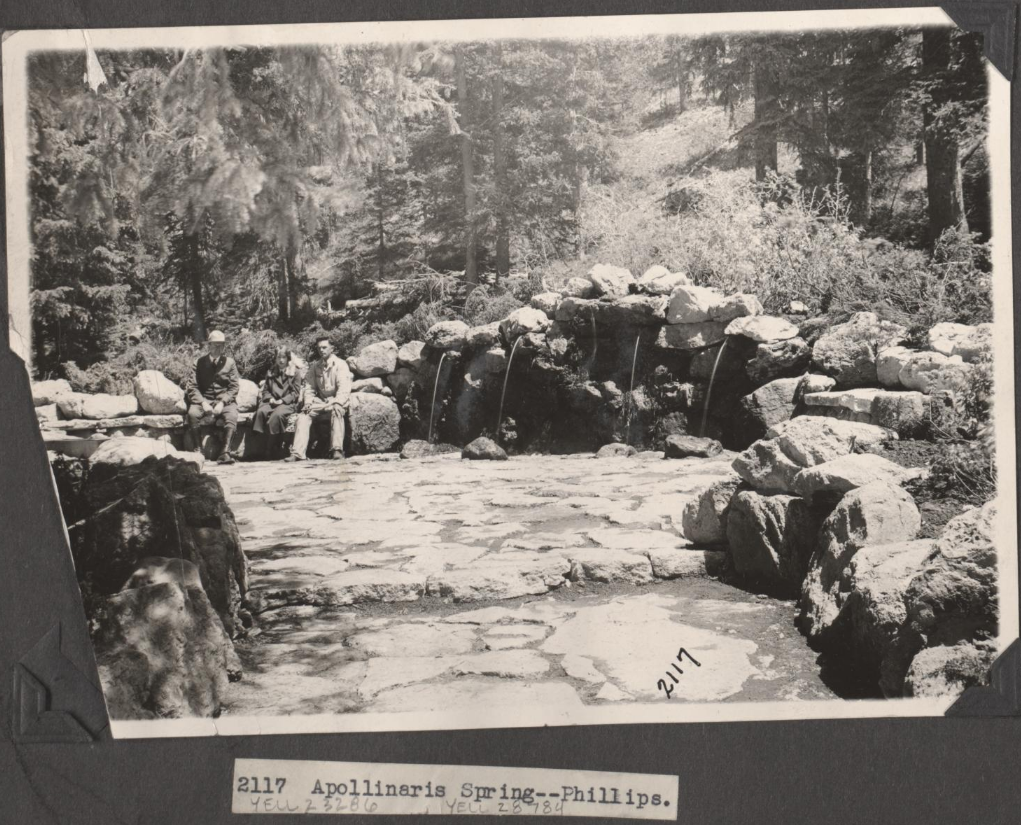

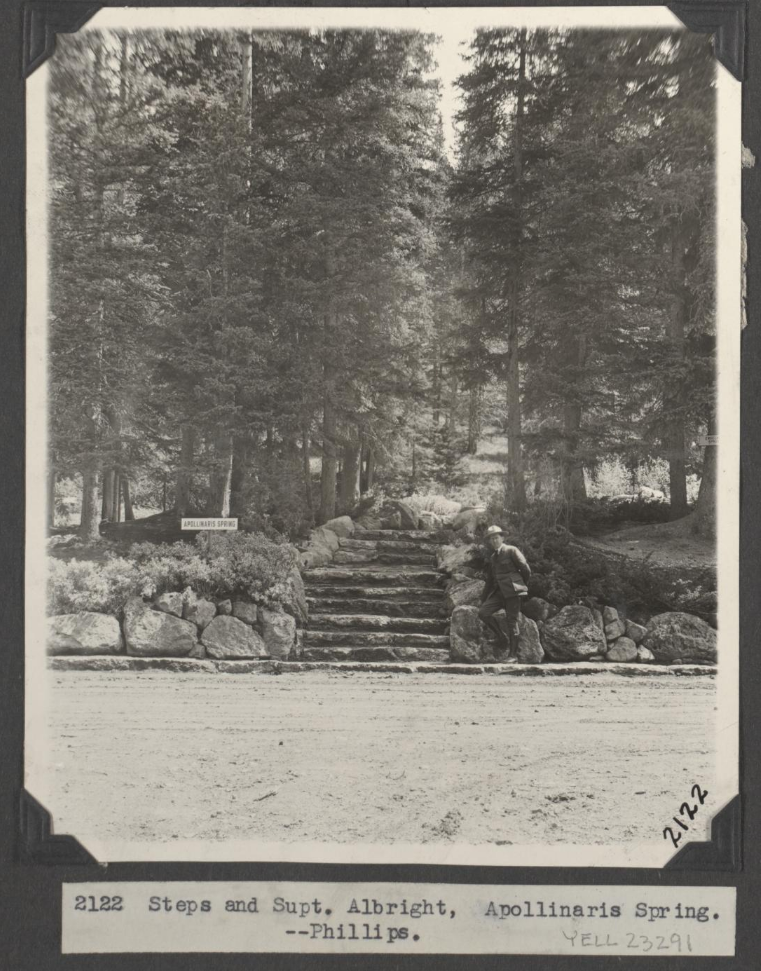

Amidst these changing times, the NPS, tasked with handling both the human and nonhuman sides of national parks, opted to bridge the two as much as possible, with a hefty preference for human enjoyment. They had their druthers, so to speak. Among the tendencies exhibited by NPS management around this time was to build upon Yellowstone’s reputation as a “wonderland,” a sort of natural playground for the increasingly independent-minded horde of tourists.

Prior to the NPS, Apollinaris Spring had been more or less left alone. Under new management, however, the agency remade the entire area, as explained in the “Inside Yellowstone” video above. You can see pictures of the progression above.

From Past to Present

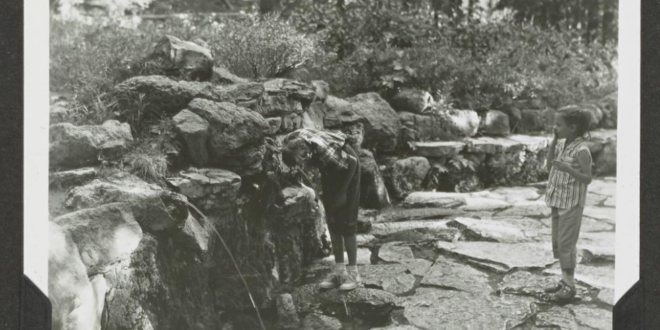

Visitors can still visit Apollinaris Spring as they tour the park, but there is a crucial difference. Unlike the visitors above (and unlike the children in the top photo of this article) you can’t drink the water. Or, rather, you shouldn’t.

There are a few reasons for this. First of all, as Janet Chapple notes in Yellowstone Treasures, the water has tested positive for giardiasis, an intestinal disease. Secondly, per the video, the water from Apollinaris Spring is used for neighboring restroom facilities. Finally, to drink from Apollinaris today would be a flagrant rebuke of what visiting Yellowstone has become.

As mentioned, Apollinaris Spring has been a tourist attraction about as long as tourists have visited the park, however informally at first. The decision to construct the rock fountain and steps only solidified this notion. But Yellowstone isn’t just for tourists. It’s for the wildlife and the geologic marvels and the cultural heritage and the inheritance of future generations—a fact prior tourists were ignorant of in terms of their behavior.

Artifacts like Apollinaris don’t harken back to a more innocent time as much as a carefree one—in that visitors and managers alike didn’t care about turning a natural source into a manmade feature. It’s a creation of the same line of thinking that spawned travertine tchotchkes and the bison showpen. It’s the same line of thinking that prompted visitors to scrape off bits of geyserite and clog up Morning Glory past the (probable) point of no return.

Which isn’t to say you shouldn’t visit Apollinaris spring. Please do! But be mindful of your behavior and your surroundings. And if you can be generous about the foibles of previous visitors, you can imagine you’ve just stepped off the stagecoach for a little rest in America’s Wonderland.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.