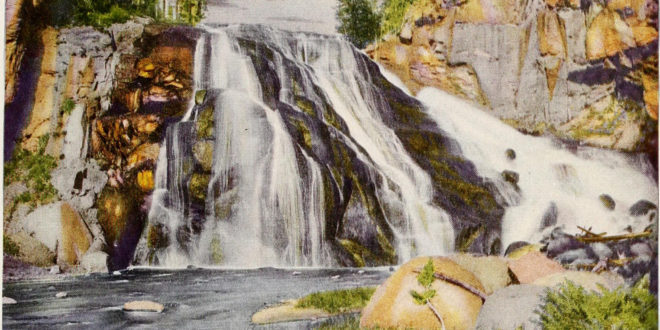

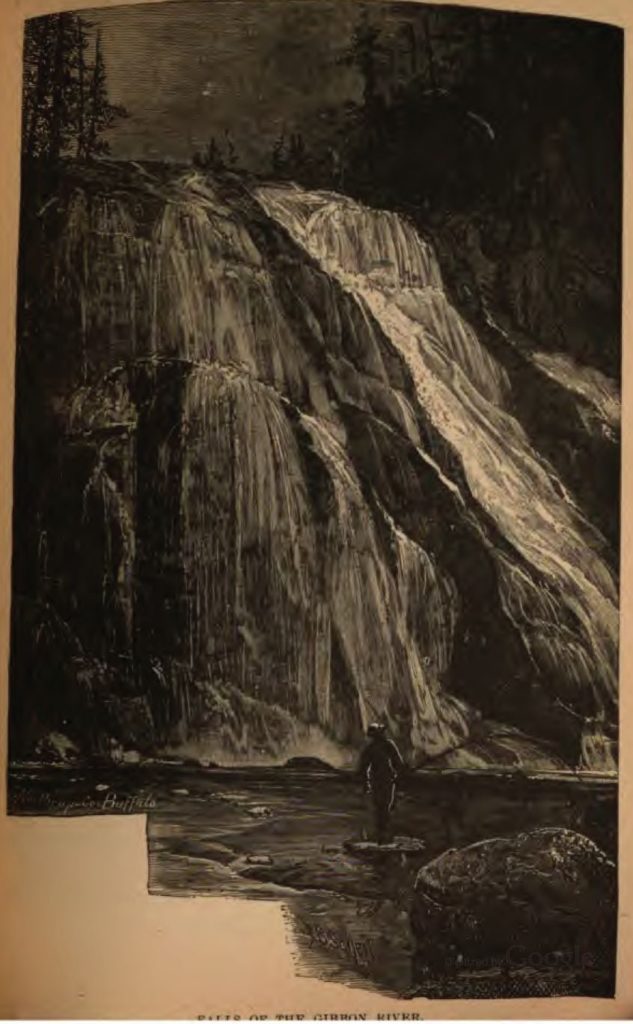

Falling 84 feet along the Gibbon River, Gibbon Falls has been a perennial delight for Yellowstone National Park visitors since the 1880s.

It’s one of the easiest waterfalls in the park to see up-close, or at least closer than, say, the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone. Just pull into the parking log adjacent to the Grand Loop Road, between Norris and Madison, and be mindful of the slope as you watch Gibbon undulate and charge. Yellowstone historian Hiram Martin Chittenden praised Gibbon as “withal one of much beauty,” in spite of its “irregular outline.”

The feature is also of geological interest, according to Lee H. Whittlesey, writing in Yellowstone Place Names: “Gibbon Falls is believed to drop over part of the wall of the Yellowstone Caldera, which is thought to be 640,000 years old.”

The current ease of access belies a once more arduous approach that interested parties had to undergo. Whittlesey notes the road once ran to the east of the falls, instead of its current trajectory to the west. Travel writer Henry J. Winser described it as an apt reward for the “stalwart tourist” in his 1883 book The Yellowstone National Park: A Manual for Tourists.

It was very difficult to get to initially and—in fact—its very name reflects this difficulty. Aaccording to Aubrey L. Haines, writing in Yellowstone Place Names: Mirrors of History, Gibbon Falls’ namesake had his name “attached to [the Gibbon River] and a number of features along it because of his failure to complete an exploration of the stream.”

Origins

According to Whittlesey, the falls themselves were discovered by members of the Hayden survey in 1872: geologist A.C. Peale, photographer William Henry Jackson and botanist John M. Coulter. The name derives from the river, which derives from Colonel John Gibbon, a Civil War veteran assigned to the Montana Territory in the 1870s.

Gibbon was an early explorer of the park; he even tipped off Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden to the existence of Terrace Spring, adjacent to Madison Junction. Characteristically, Gibbon was always seeking new nooks and crannies in the park, new facets hitherto unobserved by white settlers.

After hearing some tantalizing gossip in Mammoth Hot Springs, Gibbon and a small contingent of explorers ventured south in search of “a new geyser basin (Norris) and a shorter route to the Firehole basins.” It so happens Gibbon and his party ran into the Hayden Geological Survey August 7, 1872, freshly tromping through the newly christened national park; it was the 1871 Survey that helped sway Congressional opinion to make Yellowstone America’s first national park.

This proved fortunate for Gibbon, as, without the Hayden Survey’s presence, he and his party may have died. The details are murky, but according to Haines, this is the most reliable explanation of the party’s mishaps:

What is known is that they went down the Firehole River to Madison Junction and attempted to ascend the stream that enters from the east. According to Colonel Gibbon, they “fell short of provisions and had to kill squirrels, blue-jays, and a pelican, and finally to grub for wild roots for subsistence.” They had to return to Madison Junction where Dr. Hayden’s division of the Survey found them in a famished condition on August 20. The surveyors were also short of provisions—in fact they were on their way out of the Park by the Madison River route—but they shared what they had with the soldiers. Hayden afterward gave the stream that had baffled the soldiers the name of Gibbon’s Fork, “in honor of General [a Civil War brevet] John Gibbon, United States Army, who has been in military command of Montana for some years, and has, on many occasions, rendered the survey most important services.

Lost Names

According to Haines, Hayden was rather generous in this indulgence of Gibbon, as he suggested a number of features bear his name. Indeed, for a brief time, Norris basin was called “Gibbon Geyser Basin,” but that changed once Superintendent Philetus Norris arrived and named the basin for himself. Norris apparently attempted to claim naming rights for the Gibbon River as well, but proved far less successful.

Gibbon’s name was used for a number of features that were ultimately renamed. The current names are mentioned in parentheses where applicable:

• Gibbon Paint Pot Basin

• Gibbon Paint Pots (Artist Paint Pots)

• Gibbon Chocolate Pots (Chocolate Pots)

However, a number of Gibbon-type features remain to this day: Gibbon Geyser Basin near Gibbon Meadows and Beryl Spring, Gibbon Canyon, Gibbon Hill and Gibbon Hill Geyser. And, of course, Gibbon Falls.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.