In spite of its name, Yellowstone’s Lost Lake is remarkably easy to find.

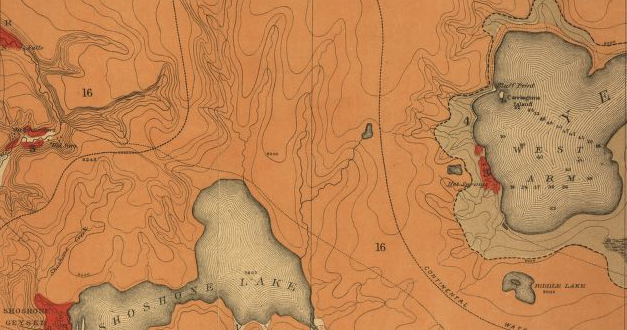

A short jaunt up the hill behind Roosevelt Lodge, this “lake” (more of a slough if we’re being honest) is a popular day hike for visitors, especially since it takes you past Petrified Tree. Just imagine how nice this sounds: a mid-morning jaunt up to Petrified Tree, followed by a meander past Lost Lake, then back to Roosevelt for some lunch? You can see that trail below, courtesy of the National Park Service.

However, I’m not here to talk about Lost Lake. Not that Lost Lake anyway.

The Lost Lake I want to discuss was (or was not) located near West Thumb Geyser Basin. The distinction is important here, since two of Yellowstone National Park’s most prolific and passionate historians have reached markedly different conclusions over Lost Lake’s location and existence—a question that stems from the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey.

Origins

Historian Marlene Deahl Merrill, in Yellowstone and the Great West, singles out a passage in geologist Albert C. Peale’s diary that makes apparent reference to the lake when the party was passing near Yellowstone Lake Sunday, August 6, 1871:

Towards sunset [chief topographer Anton] Schönborn and the Doctor came to the conclusion we were lost so we decided to camp at the first water. The soldier and horse with [guide] José stayed behind to rest. About a mile and a half further we came to a small lake about 1 mile wide and 2 long which was not down on the map and must be the headwater of one fork of the Snake River. We are away to the south of the Yellowstone Lake.

In her explanatory note, Merrill notes Hayden’s take on the lake and subsequent developments in park literature:

Hayden observed that the lake had no outlet and was “simply a depression which receives the drainage of the surrounding hills.” He calculated that the lake was about two miles long and one wide and further observed that the water was not clear and cold as in other mountain lakes. Named in 1885, Lost Lake appeared on park maps after 1871, placed on or near both sides of the continental divide in the vicinity of Norris Pass. Up until 1939, fishermen and rangers described the lake in documents held now in the park archives.

In her note, Merrill explains the split in opinion between historians Aubrey L. Haines and Lee H. Whittlesey; the former maintained Lost Lake never existed while the latter says it once existed. Both agree that the feature is no longer in Yellowstone. But both reach that conclusion by following different routes that, interestingly enough, start from the same place.

Whittlesey’s Take

Whittlesey, in Yellowstone Place Names (1988, revised 2006), harkens back to Hayden’s initial entry and subsequent park literature, including accounts from Hiram Martin Chittenden (Haines and Whittlesey’s unofficial predecessor) and packers, to substantiate Lost Lake as a real Yellowstone place:

Captain W.A. Jones’ map 36 of 1873 showed both the lake and his packtrain’s campsite very near it, but if they saw it, Jones did not mention it. Superintendent P.W. Norris’s maps in 1879 and 1880 showed the lake resting squarely on the Divide, and he labeled it “Two Ocean Pond.” According to Chittenden (1895, p. 332), Hague survey members named it Lost Lake in 1885, although why is not known. Their 1886 map showed it unnamed on the Pacific side of the divide. Maps of 1896, 1904, 1912, 1921, and 1930 all showed Lost Lake on the Atlantic side of the divide and only a couple of miles from the main road.

In 1937, following many inquiries from fishermen and others as to why this mapped and (supposedly) good-sized lake could not be found, Ranger Trusten Peery asked the advice of old-timers in the area. He was told that Billy Ferrell (probably the son of James Ferrell, an early and longtime Paradise Valley rancher) had succeeded in finding the lake in 1915 while searching for a lost horse. Ferrell had reportedly tried his luck fishing at Lost Lake with splendid success. A packer named Jack Meers told Peery that he too had often visited the lake to fish (last in 1921), saying it was about 3 miles southwest of West Thumb village, and had been misplaced on the map (Peery in Yellowstone Nature Notes 14#9-10, pp. 41-42).

Whittlesey also notes that, after The Denver Post ran a story about Lost Lake (“Park Engineers Search for Lost Lake in Wyoming, July 3, 1938), ranger Felix R. Oberhansley set out August 8, 1938 to find Lost Lake. Per Whittlesey, Oberhansely found it after four and a half hours.

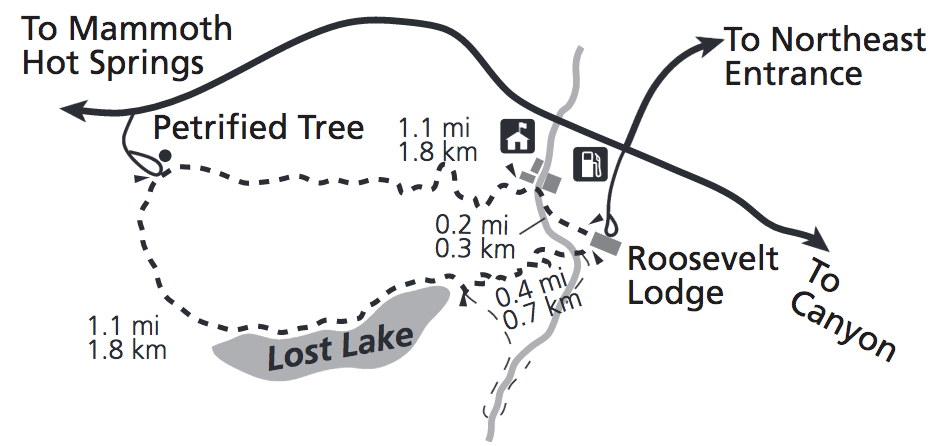

By the time Whittlesey started writing Yellowstone Place Names, however, Lost Lake really was lost. Whittlesey cites an entry from the 1966 Haynes Guide alleging that the feature had dried up and become overrun with vegetation. You can see a map from the 1953 Haynes Guide above, depicting the purported location of Lost Lake. Whittlesey later cites the most up-do-date topo map of the region (at the time of initial publication, that was the 1986 7.5-minute map of Craig Pass, Wyoming) as a guide to explaining where Lost Lake might have been—if we’re operating under the assumption that Lost Lake existed in the first place.

Haines’ Version

Without naming him, Whittlesey rebuts “one historian” who maintained the feature never existed. That historian was, of course, Whittlesey’s predecessor, Haines.

In his own book of Yellowstone nomenclature, Yellowstone Place Names: Mirrors of History (1996), Haines maintained that Lost Lake was “an ephemeral body of water variously placed on Park maps as a feature on or near the Continental Divide between West Thumb and the Shoshone Lake drainage.”

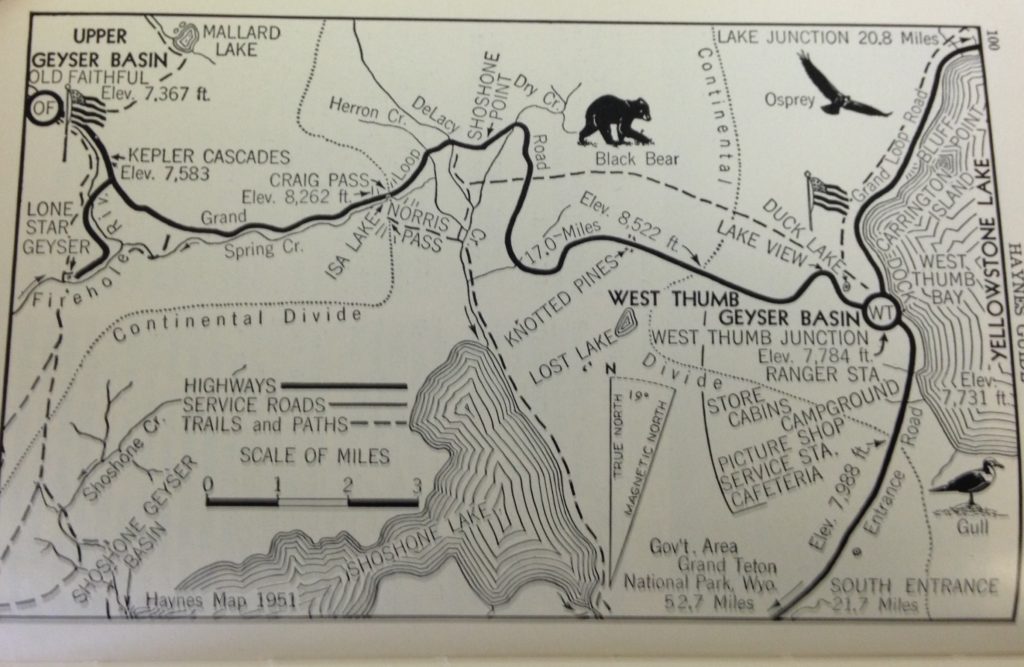

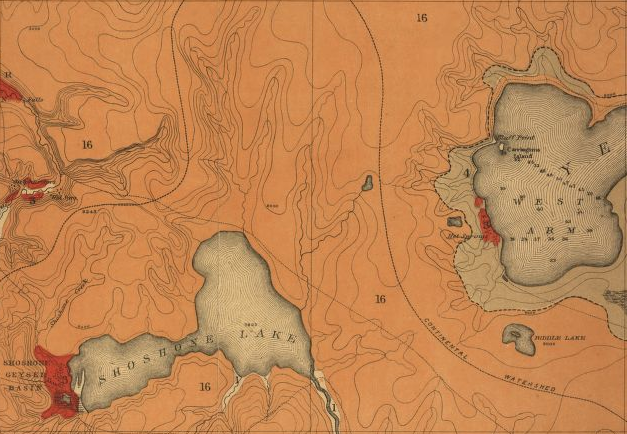

Like Whittlesey, Haines acknowledges Hayden’s description—and subsequent naming by Norris—of a small feature there. Indeed, the Hayden Survey included the feature on an 1878 topo map. However, the feature was unnamed, and far smaller than either Peale or Hayden’s estimates (less than a half mile long instead of two). As mentioned, Norris named the feature “Two Ocean Pond” in 1880 and the name was later changed to Lost Lake. Below is a portion of a “Preliminary geological map of the Yellowstone National Park,” created by the Survey in 1878, which you should compare with the Haynes map above. “Lost Lake” should be the little blob center-right.

Haines maintains this incongruity, paired with later survey data, obliterates any factual basis for Lost Lake. Haines also tears apart anecdotal sources, including the ones Whittlesey uses in support of his claim. From Yellowstone Place Names:

Geological Survey maps from the Shoshone quadrangle (1886) through the 1954 revision of the Park-wide topographic map showed the lake as “Lost Lake,” but with the same size and shape as on the earlier maps. However, although they kept the lake nearly on the Continental Divide, it was moved a mile south of the highway, where it remained for more than 68 years—until completion of the aerial survey upon which the 1956 West Thumb fifteen-minute quadrangle was based.

The verdict of the aerial camera, which proved that “Lost Lake” never really existed, should have been accepted as final—but it has not been. Haynes Guide remains its champion to the last edition (1966), which stated, at Mile 4.20 out of West Thumb: “Earlier maps showed Lost Lake about a mile (air-line) southwest of this point on the road. Present maps, made from aerial photographs do not show this lake, which may have been covered with vegetation when photographed from the air.” Indeed, a place name study that appeared, only last year echoed that thought—“It is possible that Lost Lake, like other glacial lakes, has filled with vegetation.” Such suppositions betray a complete lack of knowledge of the process of photogrammetry, which is quite capable of differentiating a vegetation-choked pond from meadow grass, a sagebrush flat or a lodgepole pine forest. These attempts to somehow authenticate the Lost Lake name are based on a reluctance to give up some rather gaudy tales told in past years, particularly those reminiscences gathered by Ranger-Naturalist Trusten Peery in 1937. Those accounts describe a fishable lake visited by different individuals in 1915 and in 1921, but the directions given lead to localities a considerable distance apart in areas subsequently traversed by forest-type mapping crews, blister-rust control parties, and fire fighters—none of whom found the lake—so that it is hard for me to believe it ever existed.

Haines notes Whittlesey’s objections in an afterword, of sorts, to his initial Lost Lake entry, adding nonetheless, “I suggest the foregoing should be taken, if at all, Cum grano salis!”

A Question of Historiography

Merrill, in her explanatory note, doesn’t pick a side, merely calling the identity of the feature Peale and Hayden discuss “unresolved,” adding, “whatever it was or is, it clearly existed at the time Hayden’s small party camped on its shore.”

More than anything, however, the split in opinion between Haines and Whittlesey is remarkably pertinent vis-à-vis the question of historiography, or the study of writing history.

Look, for instance, at Whittlesey’s thesis: “While one historian claims there is no basis for this lake’s ever having existed, the evidence of many accounts of persons who found it is too extensive for doubt.” Now, compare that with Haines’ thesis: “The verdict of the aerial camera, which proved that “Lost Lake” never really existed, should have been accepted as final—but it has not been.”

There’s a lot of daylight between those two statements but this, I feel, is the most important takeaway: using the same sources, Haines and Whittlesey reached staunchly different conclusions.

It’s clear that Haines has a disdain for “gaudy tales” made by packers and other nonprofessionals, preferring the expertise of rangers and the testimony of photogrammetry. Whittlesey, meanwhile, finds the sheer number of “Lost Lake” stories (including these “gaudy tales”) lend credence to its one-time existence.

You may ask why this matters. Confirming or negating the existence of a small lake—one that no longer exists, mind you—may seem like historical peanuts compared to “the big picture.” It would be a bigger revelation, for instance, if we found out that William Henry Jackson wasn’t the first photographer to snap a pic of Old Faithful or if some unearthed document lent credence to the now debunked “campfire myth.”

In terms of ground shaking Yellowstone discoveries, those would rank high on the Richter scale. But questions like “was there ever a Lost Lake near West Thumb Geyser Basin?” are just as ground shaking, albeit on a lower scale. Remember, the question of Lost Lake dates back to 1871, a pivotal year in Yellowstone National Park’s history—and the Hayden Survey remains its most credible explorers.

Possibilities

At present, the question of Lost Lake seems more or less settled. But who knows? Maybe someone could follow up on Whittlesey’s conjecture and go take soil samples from the three areas around Craig Pass he suggests. Maybe such an undertaking would only strengthen Haines’ case.

It’s fascinating to think about—irrespective of whether anything new is proved or debunked.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.