By most estimates, the Cottage Hotel in Yellowstone National Park ranks low on the list of lost Yellowstone landmarks.

More or less a big shack by the time it was torn down in the mid-1960s, the Cottage Hotel nevertheless outlasted several beloved Yellowstone facilities—the Fountain Hotel, Norris Hotel, even Robert Reamer’s opulent Grand Canyon Hotel.

The Cottage Hotel began auspiciously enough as a business venture by the Henderson family, who, like the Haynes and Hamilton families, were as close to Yellowstone aristocracy as you got. In volume one of his monumental Yellowstone Story, Aubrey L. Haines provides a quick primer on Cottage’s origins:

During 1885, Mammoth Hot Springs acquired its third hotel, the Cottage, built by the Cottage Hotel Association, a Henderson family concern, on land leased to Walter J. and Helen L. Henderson (son and daughter of Assistant Superintendent George L. Henderson). The Cottage competed with the National Hotel, providing lower cost lodging, until 1889 when it was sold to the Yellowstone Park Association.

Note: The National Hotel is today’s Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel and Cabins.

In another book—Yellowstone Place Names: Mirrors of History—Haines explains that the Henderson family received a ten-year lease for the site March 3, 1885. Haines speculates that some political maneuvering on the part of David B. Henderson—then-Speaker of the House in Congress—might have scored them the lease.

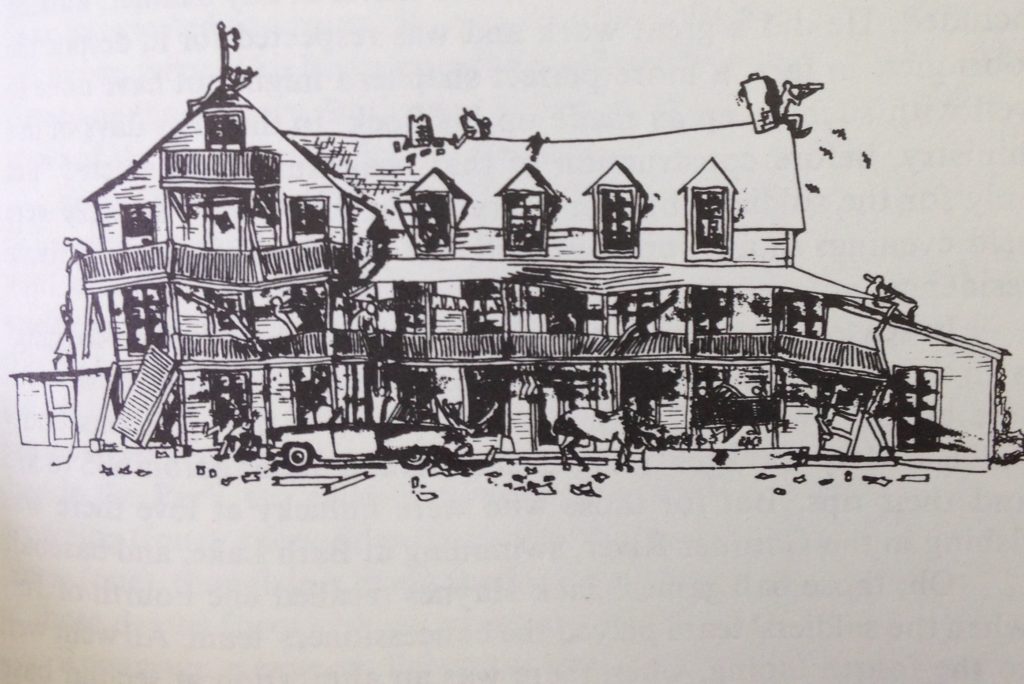

In appearance, the Cottage Hotel was rather homely when compared to the neighboring National. Three stories, log exterior, and no frills. You can be sure that the ride up to Cottage did not feel as grand as the pull-up to National’s long covered porch.

A Change in Fortunes

The Cottage Hotel did not remain long in Henderson hands. Shortly after the hotel was built, George G. Henderson (not to be confused with the assistant superintendent) entered into a partnership with Harry Klamer, the founder of Klamer’s Curio Store in Old Faithful, which became the lower Hamilton Store. Klamer organized the Cottage Hotel Association. According to Haines, G. Henderson sold his share to the Association sometime before 1889, when both the Cottage and National Hotel were sold to the Yellowstone Park Association.

While the National Hotel was held in high regard as one of the premier lodging facilities in Yellowstone National Park, Cottage languished as the budget option, a reliable but not much-loved facility. In fact, to call it a hotel is, by and large, erroneous; after a few years it was converted into a dormitory for employees.

“A Maximum of Confusion”

According to Haines, writing in volume two of The Yellowstone Story, by the 1910s Cottage had fallen into disrepair. Not serious enough to tear down, perhaps, but serious enough that it was not a viable hotel. But it gave the volunteer fire department, composed of soldiers living in the far nicer accommodations at Fort Yellowstone, something to save. From Haines:

Soldiering was not all of life at Fort Yellowstone. The soldiers were organized in a fire brigade, just as government employees at Mammoth Hot Springs are today. Scout Ray Little recalled one turnout in response to a fire call from the Cottage Hotel, which was then (1910) used only as a dormitory during the summer season. The fire brigade responded promptly and managed to suppress the fire (a small blaze in the attic) with a maximum of confusion. As Ray told it, the eager “swaddies” were busy carrying mattresses down the stairs and throwing chairs and china washbasins down from the second-story balcony when there was a diversion that temporarily stopped the show. A young lady known as “Twee-tweet,” who worked a night shift at the National Hotel, was asleep in one of the upper rooms in a state of undress, and the racket raised by the fire crew frightened her onto the street without thought of apparel. She was quickly supplied with a blanket so the business of fire suppression could go on. The fire fighters were rewarded with a round of beer, but privately the president of the hotel company expressed disappointment that the old log structure had been saved.

Indeed, later Yellowstone employees had a dim view of the “Cottage” as well, rightly labeling it a wreck. In an undated photo from Mr. Haines’ collection (shown above), one employee depicted the building in a sorry state of disrepair: balustrades collapsing, porches sagging, tiles missing from the roof, bats(?) or swifts(?) swirling round the chimney as adventurous souls climb all over its decrepit frame.

Further, the hotel seemed to exude disorder. Haines reports that beer could no longer be served to soldiers at the Cottage Hotel after too many brawls broke out. They had to go to Gardiner, famed then for its “collection of groggeries.”

Demise

By some miracle, the Cottage Hotel managed to stand for several more decades after its brush with immolation in 1910. The 1953 Haynes Guide makes a small reference to it as “the oldest remaining building in the[Mammoth] village.” According to Haines, it took until May 4, 1964, for the building to be razed—after it had stood vacant for several years. You can see evidence of its sorry state below, in a photo taken by someone named McIntyre in 1959.

But consider that the Cottage, more or less expunged from Yellowstone’s memory, outlasted some of the Park’s more famous, more expensive hotels.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.