When David Quammen was asked to write the body of National Geographic’s May 2016 issue on Yellowstone National Park, he was surprised.

“It was a little bit flattering but also daunting—a lot of responsibility—and I thought about it very carefully for about three seconds and then I said yes.”

Initially, Quammen was just one of many writers National Geographic had at their disposal (“I was part of their stable of guys”) but Quammen had a leg-up on his colleagues, since he just happened to live in the Yellowstone ecosystem.

“The editor-in-chief at that point was a wonderful fellow named Chris Johns,” Quammen said. “He’s moved up in the National Geographic since but Johns was the one who conceived this idea. ‘Here comes the Centennial of the National Park Service—2016—we’re going to do a series of stories on national parks throughout the course of the centennial year but we want to do one very special issue entirely devoted to the first national park and its ecosystem, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.’”

Quammen hoped, as he consulted and advised with his friends and colleagues at National Geographic, he would land a contributing role to the project. Apparently, Johns had other plans, once he saw Quammen in Bozeman.

“After I helped them think about it they flew back to Washington, and a few days later Chris Johns called me and he said, “David, I’ve been thinking about this. We’re going to have a team of photographers on this, but I want the text part to have a unity of voice, so why don’t you write the whole thing?”

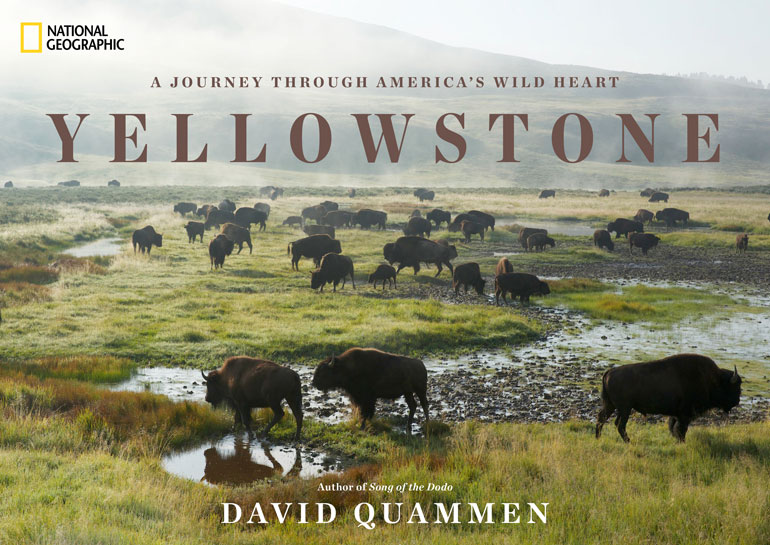

Johns also proposed making a book version of the magazine article, entitled Yellowstone: A Journey Through America’s Wild Heart, which proved fortuitous for Quammen.

“The magazine text was around 15,000 words long and the book is about 25,000 words, so I picked up pieces from the cutting room floor that did not fit into the magazine version, and I put them back into the book version. The structure is the same, message is the same, but there are some things that just wouldn’t fit into the magazine version that I wanted to include and those are in the book version.”

According to Quammen, the Yellowstone book contains more information on wolves in the Park, as well as interviews with area ranchers whose land—surprisingly enough—provides the same function for wintering wildlife that makes the Park so valued. It also contains a fascinating example of what Quammen calls “the paradox of the cultivated wild.”

“I went on a backcountry ski trip with the chief bear biologist and the chief wolf biologist to a place called Heart Lake,” Quammen said, “and while we were at Heart Lake I learned the story about the grizzlies in the Heart Lake area used to hibernate and then they would come out in the spring, desperately hungry. They would find elk carcasses left from winterkill, because a small herd of elk would winter in the Heart Lake area because there were some thermal features, and they kept some grass open during the winter, it was a good place, but a few elk would still die and the grizzlies would eat them first thing out of their dens.”

This all changed, however, when wolves were reintroduced to the Park; eventually, they chased off Heart Lake’s winter elk herd, leaving the hibernating grizzlies deprived of an important food group.

“Now the grizzlies have just lost their spring food, their first and most crucial spring food. What are the grizzlies going to do? Do the grizzlies leave that area and no longer den there? No! The grizzlies adapt, adjust, and now they eat earthworms… digging earthworms out of the side of the hillsides, which is peculiar and surprising.”

Quammen says there’s another layer to the story, which is where his paradox comes in.

“And the biologist is telling me all this and then he says, ‘well here’s the further irony: earthworms are exotic species, they’re not native, they were brought in from Europe on horticultural products.’

“So it was just to me a rich example of a couple of different things: the fact that as foods change, grizzlies have to adjust, they have to adapt and they have a great degree of flexibility. They’re very enterprising. And that exotic species, invasive species, are a problem in Yellowstone and yet at times, ironically … a particular invasive species may be the solution to a problem.”

For Quammen, wildlife such as grizzlies and wolves are just one example of Yellowstone’s splendors. One other big attraction of Yellowstone is its preservation of “the important ecological processes, basic ecological processes, wild Western landscape,” a landscape where “predation and scavenging and competition and migration and photosynthesis and decomposition and infection” are allowed to continue more or less unmediated.

Quammen, both in Yellowstone and in speech, attested to the changes underway in the Park, both from climate change and cultural shifts. He spoke at length about how tourism is affecting the Park, especially as more visitors come from abroad—especially from China, noting that Chinese restaurants and Mandarin signage have cropped up in West Yellowstone.

Where some might disapprove outright, however, Quammen is ambivalent about the rise in tourist numbers, weighing their pros and cons for Yellowstone.

“The visitor numbers are exploding … and the breadth of world diversity of visitor numbers is increasing. And that’s good for the Park—you want it to be popular, you want it to have visitors, you want it to have a constituency—but there’s also a bad side to that cause greater visitor numbers cause greater impact.”

Quammen went onto say the biggest challenge both Yellowstone and neighboring Grand Teton will face in the coming years is meeting demand for the Parks—or whether to restrict demand entirely by banning private car usage or instituting a permit system or lottery. Quammen believes the latter will rule out, especially with people like Yellowstone superintendent Dan Wenk and Grand Teton superintendent David Vela at their respective helms.

Still, Quammen does see the plus side in the increase in visitation, especially from Chinese tourists—a testament to Yellowstone’s lovely, persuasive landscape.

“I would love for these people to go back to China with this understanding that Yellowstone is a magical, important, precious, vulnerable place. It’s good for there to be people all over China who feel that way about Yellowstone.”

Quammen added that he hopes Chinese environmental officials one day visit Yellowstone and take home its lessons on how climate change is affecting wild spaces. That’s the hope anyhow, that people find a workable solution to“the paradox of the cultivated wild.”

“It’s going to be very important to work on that, to try and keep Yellowstone wild and connected.”

Indeed, when asked, Quammen gave some predictions for what the next 20-30 years entail for Yellowstone.

Some of Quammen’s predictions are less than ideal for fans of the Park (including possible visitor caps and the likely disappearance of whitebark pines) but some are hopeful—such as the fate of Yellowstone’s grizzly bears. Indeed, Quammen predicts Yellowstone grizzlies will adapt to changes in and outside the Park—even a possible delisting from the Endangered Species List. Their survival, however, will be trickier, and may require some innovative solutions, such as connecting Yellowstone’s grizzly population with the population around Glacier National Park and the Montana-Canada border.

“That’s my greatest hope for the next 30 years—that we not only preserve Yellowstone’s population but we also manage to achieve some manner of connectivity between those two populations. And that will be a difficult challenge, not only in ecological management but in social engineering. To do that, we have to increase social tolerance for grizzly bears, on the landscape of Montana, on the rural landscapes of Montana, including private ranches.”

Quammen’s experience with the National Geographic issue and (later) Yellowstone contributed to his selection as the keynote speaker at this year’s Scientific Conference of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—an admitted honor for Quammen, who’s no stranger to public speaking—earlier this year, he spoke at the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Earth Day conference—but he admits the bar is higher when you’re addressing a scientific community and not the general public.

“Obviously when I do a keynote at the biennial Yellowstone Ecosystem science conference, it’s different from talking to people in Madison, Wisconsin on earth day. These people spend their lives studying Yellowstone so the challenge is, y’know, how do I tell them something they don’t already know? And I’ve talked a little bit about that, discussed that with the people who’ve invited me, the organizers of the conference, so I’ll get around that. I’ll talk a little bit about not only the science of Yellowstone but telling the story of the science of Yellowstone, kind of make this live for a wide audience.”

Quammen is also no stranger to the conference. Indeed, he was an attendee at the last one, while he was working on the special issue for National Geographic. But his time at the conference was memorable for a different reason. While Quammen was sitting in Mammoth, listening to scientists lecture on various topics, ebola was dominating the national news cycle—a topic Quammen is quite familiar with, having written about it in his 2012 book Spillover.

“When the ebola outbreak was happening, I was one of the talking heads that people were going to and saying, “hey, will you be on the Anderson Cooper show tonight or will you talk to China central television, will you talk to the Reverend Al Sharpton? … so I was getting all these calls—and this was happening during the Yellowstone science conference.

“So I would drive down to or be in Mammoth, which is about an hour and 45 minutes from my home in Bozeman, and I’d be there, sitting in the science conference, listening to people talk about climate change and the Yellowstone ecosystem, or wolf reintroduction in the Yellowstone ecosystem, taking notes and trying to learn what I could, and then I would jump in my car and drive back to Bozeman and head over to a television studio at the university and sit alone in a dark room in front of a camera and do, y’know, 35 minutes on the Anderson Cooper show, talking about ebola.”

Quammen added, “it was a very peculiar experience.”

Quammen will deliver his keynote for the 13th Biennial Scientific Conference of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem October 4, 2016 at 8 p.m. in the Explorers Room in Jackson Lodge in Grand Teton National Park.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.