Modern day visitors to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone may take it for granted they can just drive between each rim. It wasn’t always so.

At least, not before Hiram Martin Chittenden made it so easy.

Chittenden (1858-1917) may be better known as a historian these days (with titles including one of the first professional histories of Yellowstone National Park, produced in 1895, and a seminal three volume study of the American fur trade, published in 1902), but he got his initial start with the Army Corps of Engineers. Indeed, Chittenden served two terms in Yellowstone (1891-93, 1899-1904) during which he worked on improving the Park’s road system likely played a hand in the design of the Roosevelt Arch, or at least its origins.

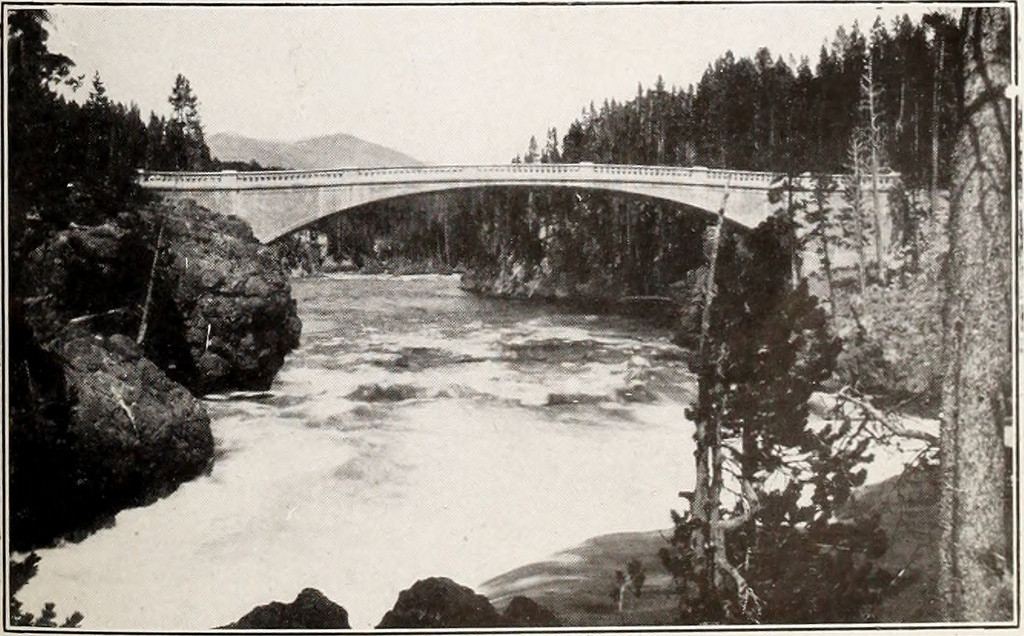

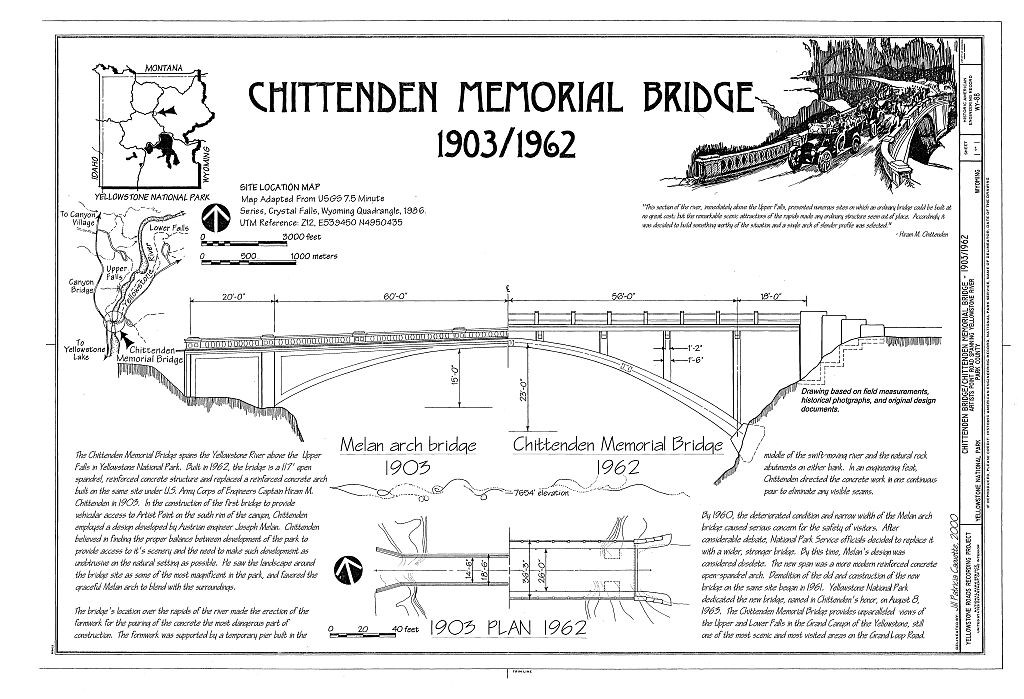

Perhaps his most noteworthy contribution to the Park was the construction of the bridge spanning the Yellowstone River, effectively connecting the two rims for the first time.

The Arch, of course, will always be a marvel, but consider that before Chittenden there was no reliable way to get from one side to the other. The 1953 Haynes Guide says a ferry manned by one Thomas Richardson used to carry visitors from one shore to another, but as the number of visitors increased, it became apparent a simple ferry would likely impede visitors hungry for fresh views of the Canyon.

The Melan System and Construction

In the 1915 edition of The Yellowstone National Park, Chittenden described building the original Chittenden bridge:

The Arch Bridge over the Yellowstone. Until 1903 there was no bridge across the Yellowstone in the vicinity of the Falls and the right bank of the Grand Canyon was practically inaccessible to the public. As some of the finest views were to be had from that side (Artist Point, for example, which Moran chose for his painting), it was considered desirable to provide means of getting across. This section of the river, immediately above the Upper Falls, presented numerous sites on which an ordinary bridge could be built at no great cost; but the remarkable scenic attractions of the rapids made any ordinary structure seem out of place. Accordingly it was decided to build something worthy of the situation and a single arch of slender profile was selected as the type of structure. The exact form was a matter of careful study in order to get the lines which would appeal to the eye as meeting the artistic requirements.

Although a complex operation, Chittenden makes the bridge’s conception and construction sound elegantly easy, perhaps borrowing the language of the bridge’s design.

The Chittenden Bridge was a variation of the Melan Arch bridge, named for its progenitor, Austrian engineer Josef Melan. Under the Melan System, steel and concrete combined to create a structure that was both functional and eye-pleasing. Indeed, according to an article in The American Architect and Building News (Volume LXXII, No. 1327, published Saturday, June 1, 1901), that marriage of utility and beauty was one of the system’s selling points both here and abroad:

The merits of [the Melan] system were quickly recognized in this country as well as in Europe. The result of such recognition has been the erection of bridges of the Melan type in parks where a handsome and aesthetic design was desired, and the displacing of iron and steel truss-bridges where permanence was the quality desired.

It goes without saying that Chittenden certainly had Park scenery in mind when he wanted to build a bridge for visitors. Of course, it wasn’t easy to just build a bridge across the river, as Chittenden relates:

The most difficult feature of the work, and the only one involving serious risk, was the building of the false work to support the forms for the concrete while in plastic condition. It was necessary to build a temporary pier in the center of the stream in the swiftest part of the rapids with the Upper Falls of the Yellowstone only a little way below. There would be small chance of escape for any one falling into the stream; but the chance was taken by one man who fell from the work, but, providentially, was caught in an eddy a little way below the bridge site and carried into shallow water near the bank.

The concrete work, contrary to usual practices at that time with such large masses, was placed in one continuous operation. This would have been simple enough with a mechanical mixer, but was much more difficult where the mixing was done by hand. Elaborate preparations were made. All the material—gravel, broken rock, sand, cement—was gathered and distributed at convenient points about the site. A date was chosen in full moon in August and a temporary electric lighting plant was installed. A force of 150 men was assembled from various road crews and divided into three shifts. When all was ready, the concrete mixing was begun and continued without intermission in 8-hour shifts for 74 hours, or until the work was complete.

Just think: a new bridge, from start to finish, in a little over three days. Modern construction crews could learn a thing or two from this Chittenden group.

Decline, Demolition, and the Chittenden Memorial Bridge

Although the bridge was completed in 1903, it wasn’t until 1912 that the Park started referring to the structure as the Chittenden Bridge. It enjoyed great popularity carrying motorists across the Yellowstone River to the other side of the rim. Although not the largest Melan arch in the world (as the 1928 Haynes Guide erroneously claimed), it was still, in all likelihood, the best bridge style for Yellowstone: functional, unobtrusive, not overpowering the scenery.

Alas, by the early 1960s, it was apparent the original Chittenden Bridge had run its course. Accordingly, the National Park Service (after much debate and some protests on the part of visitors who admired the bridge design) decided to tear down the Chittenden Bridge. They also decided not to build a Melan arch, opting instead for “a more modern reinforced concrete open-spandrel arch.” Once completed, this new structure was dedicated as the Chittenden Memorial Bridge.

The Chittenden Memorial Bridge, of course, still stands to this day, conveying visitors across the Yellowstone. And while some may mourn the loss of a historic structure like the original bridge, the spirit of Chittenden’s construction lives on.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.