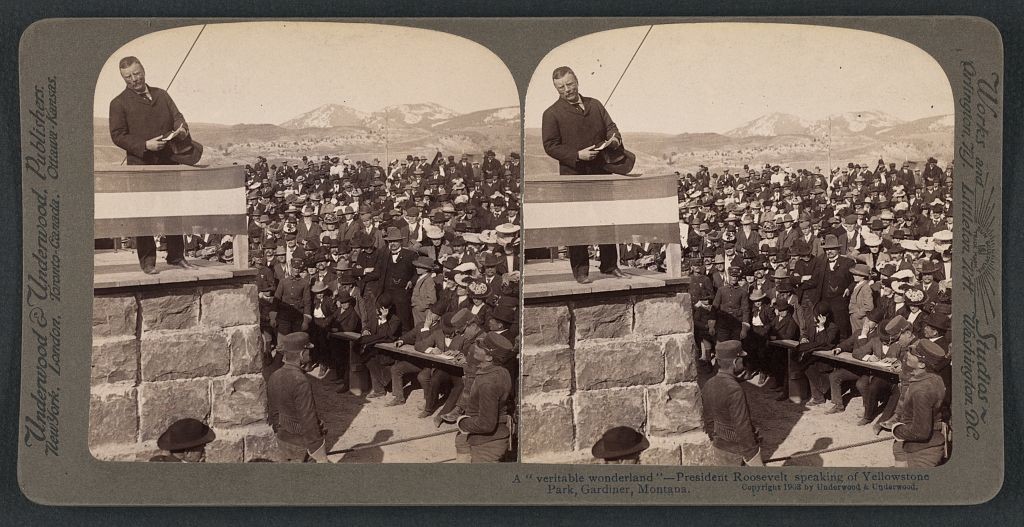

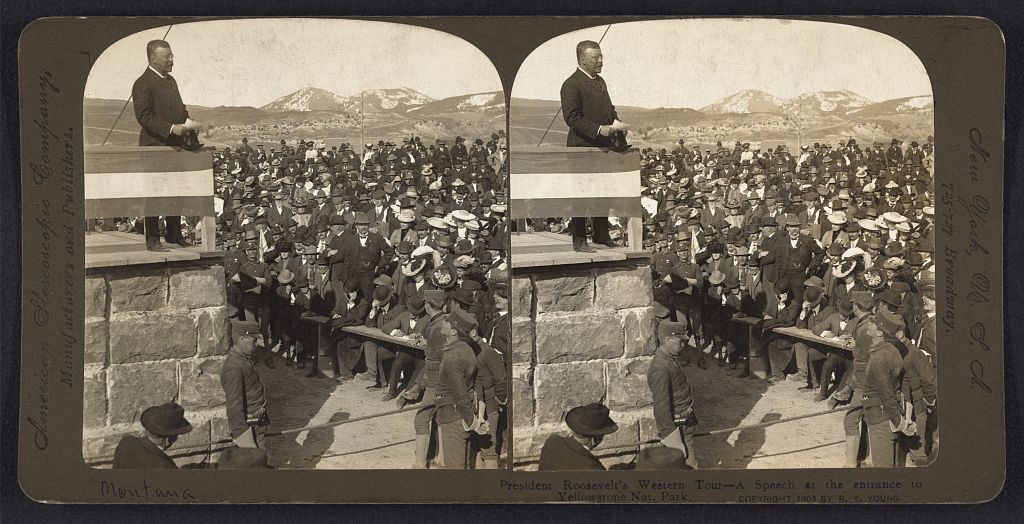

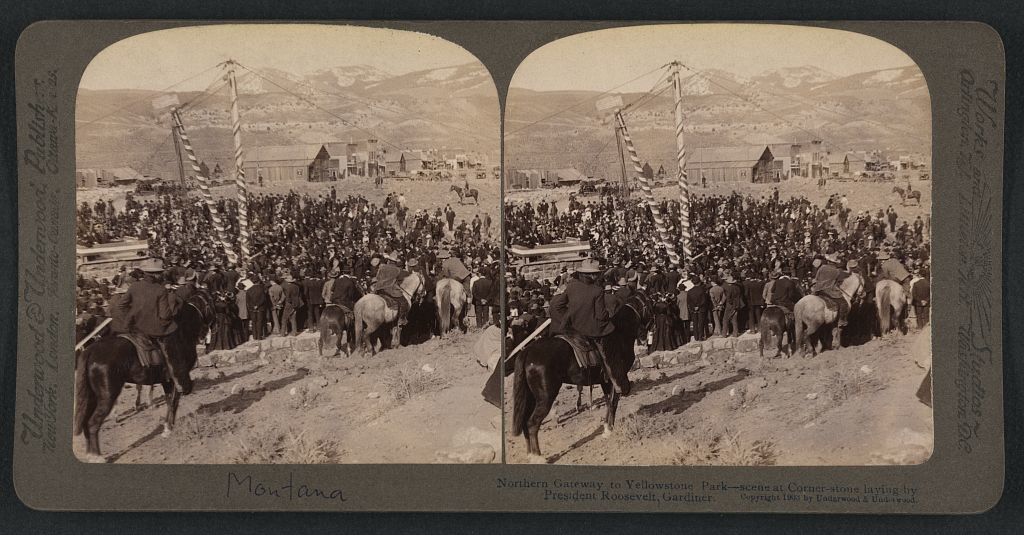

April 24, 1903: Gardiner, Montana had its “big day” with the laying of the Roosevelt Arch cornerstone.

The Arch, of course, is one of Yellowstone National Park’s most famous landmarks. A towering construction of basalt, the Arch marks the North Entrance to Yellowstone, historically the most prominent. But the Arch is also famous by association—with its namesake, President Theodore Roosevelt, who was visiting the Park when he was asked to help dedicate it. I mean, you can’t get any more grand than that.

But not for lack of trying, however. According to the Yellowstone Park Foundation, earlier plans for the arch reportedly called for two ponds and a waterfall—to “accentuate” the arch’s grandeur, not that it needed accentuating, in our opinion. Those plans were later canned as Gardiner’s arid climate wouldn’t have fostered permanent pools or falls.

Construction of the Arch took several months, from February 19 to August 15, 1903. This means, of course, that the Arch wasn’t necessarily built for Roosevelt’s visit. Nonetheless, his presence at the cornerstone laying ceremony cemented it as a sort of flashbulb moment in Montana (and Western) history. That’s how Lee H. Whittlesey and Paul Schullery see it, in their retrospective of the Arch’s centennial:

The impulse behind the arch’s construction was a matter of inspiration, convenience, and opportunity. Strange as it may seem today, there was a concern among park administrators, and some in the Gardiner community, that this most important entrance to Yellowstone National Park, nestled in an arid mountain basin, lacked sufficient visual fanfare to serve as the gateway to America’s first and most famous national park. At the same time, and on a more prosaic and commercially urgent level, the Northern Pacific’s tracks had just reached Gardiner, and the town needed a depot. And, most serendipitously, just as work got underway to satisfy these local needs, President Theodore Roosevelt decided to have a two-week outing in the wilds of Yellowstone National Park. This combination of factors, circumstances, and urges served as the impetus behind “Gardiner’s big day” in the history of the West.

Indeed, “Dedication Day” was a big to-do in Gardiner, with a huge crowd gathering at the dedication, partly spearheaded by local Masons. In fact, there were several Masonic materials (among other items of interest) placed in a time capsule containing the following items:

Indeed, “Dedication Day” was a big to-do in Gardiner, with a huge crowd gathering at the dedication, partly spearheaded by local Masons. In fact, there were several Masonic materials (among other items of interest) placed in a time capsule containing the following items:

• Copy of the World’s Almanac, 1903;

• Copy of the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Montana for 1902;

• Copy of Northern Pacific Railway descriptive pamphlet, 1903;

• Copy Masonic Code of Montana;

• Pictures of Nathaniel Pitt Langford and Cornelius Hedges, both members of the 1870 Washburn expedition;

• Original articles from the Helena Herald about the expedition;

• Copies of the Livingston daily papers;

• United States coins;

• A Bible.

Further, the stone laying was an even larger spectacle as officials had to use a crane (draped with flags, naturally) to lift the cornerstone.

Arguably, however, Roosevelt was the star that day, taking the stage along with traveling partner John Burroughs, Major Pitcher, and others.

Arguably, however, Roosevelt was the star that day, taking the stage along with traveling partner John Burroughs, Major Pitcher, and others.

The President, of course, took it as an opportunity to wax philosophic about not only the virtues and glories of Yellowstone National Park, but also the importance of judicious management its treasures. Although former Park historian Aubrey Haines reportedly described the speech as “rambling,” it was still well received. It was even reprinted in full a few weeks later in an issue of Forest and Stream magazine.

Indeed, you can sense just from short excerpts of Roosevelt’s speech that he relished the opportunity to speak passionately about the Park:

It is a pleasure now to say a few words to you at the laying of the corner stone of the beautiful arch which is to mark the entrance to this Park. The Yellowstone Park is something absolutely unique in the world so far as I know. Nowhere else in any civilized country is there to be found such a tract of veritable wonderland made accessible to all visitors, where at the same time not only the scenery of the wilderness, but the wild creatures of the Park are scrupulously preserved … The creation and preservation of such a great national playground in the interests of our people as a whole is a credit to the nation; but above all a credit to Montana, Wyoming and Idaho.

Alas, Roosevelt never returned to Yellowstone, so he never saw his namesake arch completed. But you can still see the cornerstone, just to your right as you pass under the arch. And you should take a moment to admire it. It’s still a remarkable piece of history, after all.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.