Visiting Canyon Lodge & Cabins today is to visit a changing Yellowstone—literally and figuratively.

Not only because it’s still under construction, but because its construction sets it wildly apart from existing infrastructure.

Currently, three of the five lodge buildings are open to visitors. The remaining two are slated to be finished by the end of the summer 2016 season.

The Canyon Lodge complex you see today is technically the second Lodge complex built in the area. The original Canyon Lodge was further down the road, closer to the Canyon, and was built on the site of an old Shaw & Powell Camping Co site (much like the other lodges in the Park). This Lodge and cabin complex was closed in 1957; many of the cabins were relocated to Lake.

Present-day Canyon Village had its beginnings with the Mission 66, which sought to modernize the Parks’ highway system and fully cement the place of the automobile as a means of transport. Of course, cars had been popular since around 1916 (which, traditionally, is the last year of the “Old Yellowstone Days” of rail and stage travel) but it took a long while for Yellowstone (and the rest of the Park system to really start catching up). A good way to chart this development is through the history of the Canyon Hotel, the Lodge’s predecessor and the last grand hotel built in Yellowstone National Park.

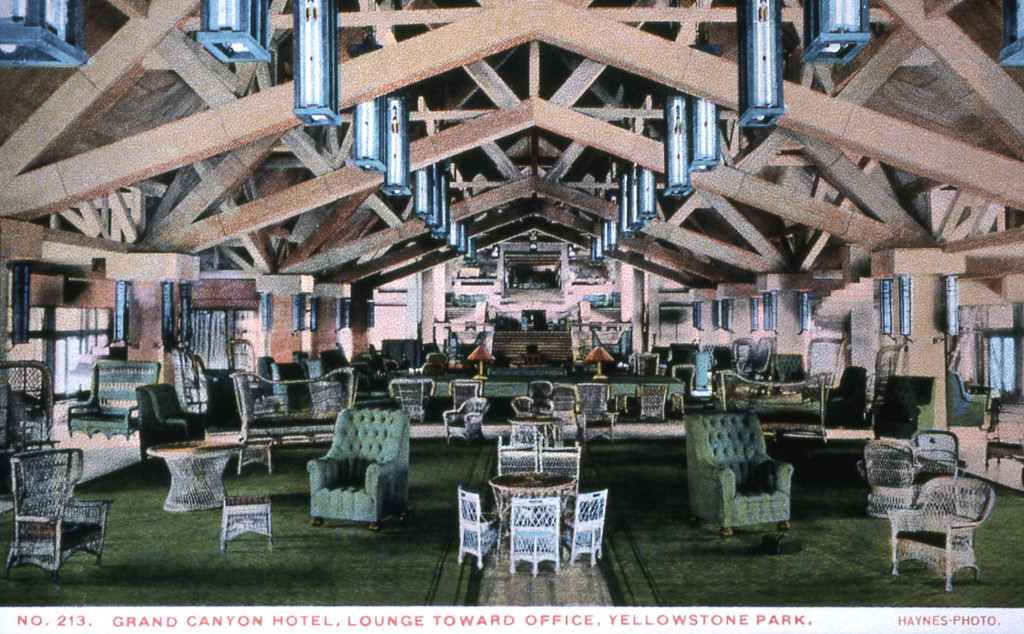

Indeed, the Canyon Hotel was one of Yellowstone’s “Big Four,” along with the Old Faithful Inn, Yellowstone Lake Hotel, and National/Mammoth Hotel. It was the last to be built (it opened in 1911) and, in some quarters, was hailed as the best. The Yellowstone Park Hotel Company certainly felt quite proud of it; they even financed a lavish pamphlet by John Henry Raftery documenting the construction and opening of the hotel. From “A miracle in Hotel Building:”

Unity without harshness, great size without ostentation, strike the beholder with his first view of the new Canyon Hotel. Without yielding anything of its own well-contained individuality, its surrender to the vast nobility of the scene in which it is placed, is complete, natural and captivating. Not of great height, of uniformly warm, bright color, never in ornate competition with the landscape about it, expressive of repose and strength, innocent of fantastic pretense or ornate frivolity, the new hotel by the Yellowstone in the National Park is an architectural triumph of singular and striking symmetry with its natural environs.

The even apex of its rambling roof-line is always uniformly horizontal, and yet the base-lines of the foundation cling faithfully to the eventful contour of the mountain-slope in lines of uneven and yet beautiful symmetry which suggest that the architect esteemed obedience to and sympathy with the master landscape gardening of Nature herself.

A tad hyperbolic, perhaps, but Canyon’s praises were loudly sung in and around Yellowstone. And for many years, it was hailed as one of the best hotels in the Park—if not in the state of Wyoming as a whole.

As mentioned, however, by the end of its life, much had changed to make Canyon Hotel obsolete. Indeed, besides the construction of Canyon Village (better suited to accommodate vehicle traffic), inspectors found the Hotel’s foundation was in dangerous disrepair. Officials closed the hotel in 1958.

But it was never torn down. For one reason or another, the Hotel spontaneously burnt to the ground in 1960. Such was the end of a building hailed for its “sympathy with the master landscape gardening of Nature herself.”

Fast-forward the early 1990s, when two new buildings were built to supplement the existing cabins, which had begun to show their age. The first, Cascade Lodge, came in 1992. Dunraven Lodge followed in 1998. For a brief time, before the construction of the Old Faithful Snow Lodge, these were the newest lodging facilities in Yellowstone National Park.

Once again, however, Canyon has overtaken Old Faithful in newness, although it borrows, in part, from the Snow Lodge’s example. Indeed, the new Canyon Lodge facilities place an even greater emphasis on recycled materials than the snow lodge, which derived much of its materials from previously torn-down buildings in the Park.

For instance, the wood paneling in all the rooms (along with the trim) comes from pine trees killed by mountain pine beetles, while the countertops are made from fly ash (a coal combustion byproduct) and recycled glass. Further, Xanterra hopes the new lodging facilities will attain some manner of LEED (“Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design”) rating from the U.S. Green Building Council.

With the construction of its new lodges (both finished and pending), Canyon Village will become the largest hotel complex in Yellowstone National Park. And, for better or for worse, it will set the tone for how visitors will see Yellowstone, and how lodging will be considered in the future.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.