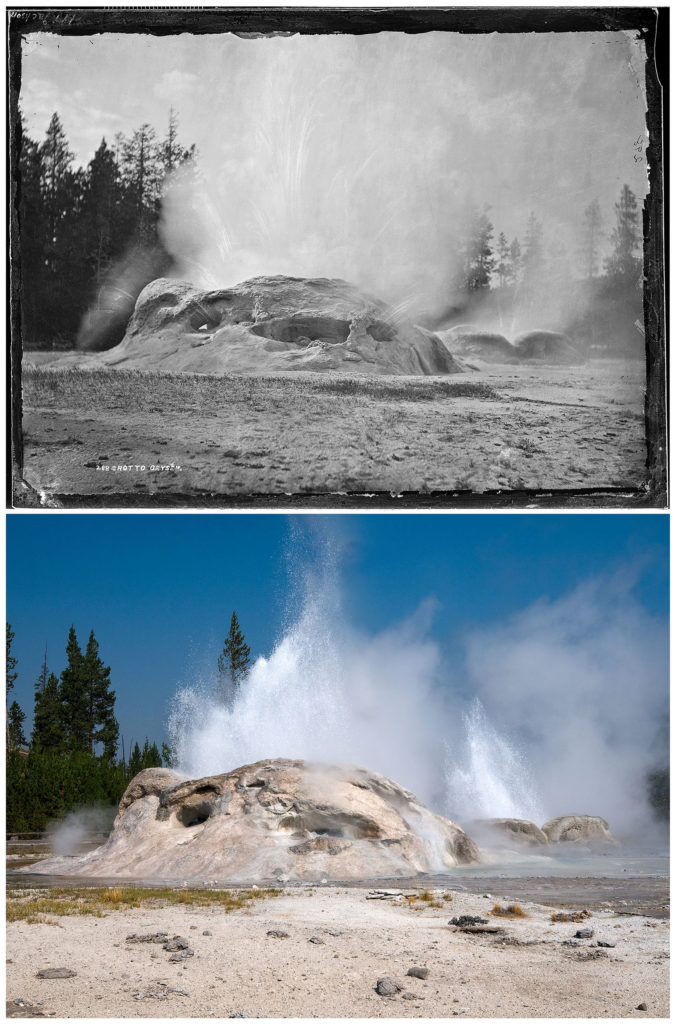

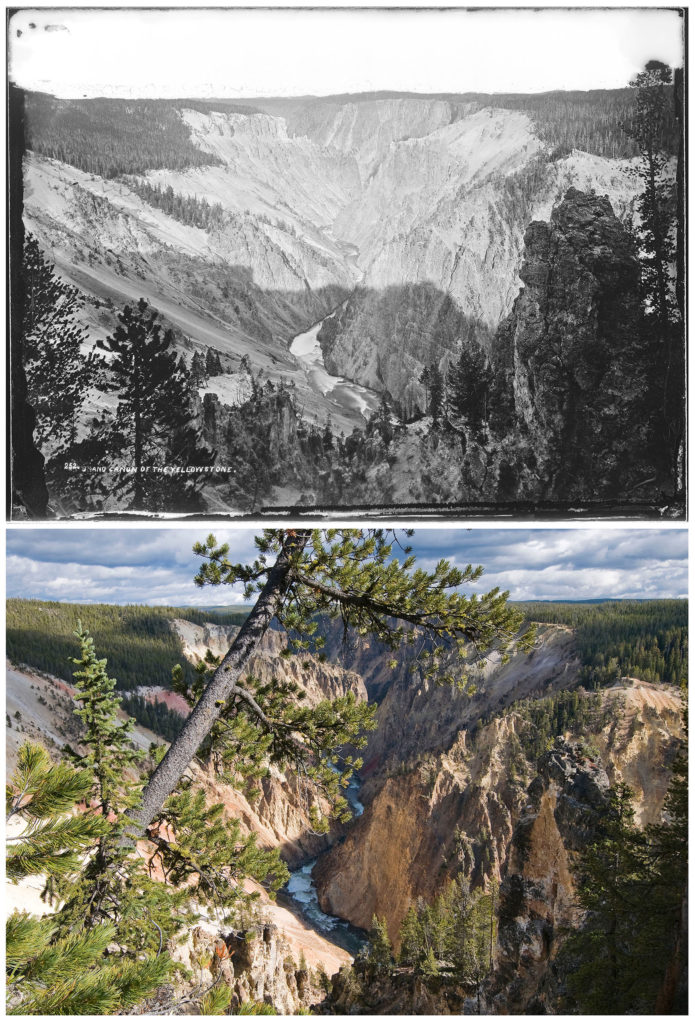

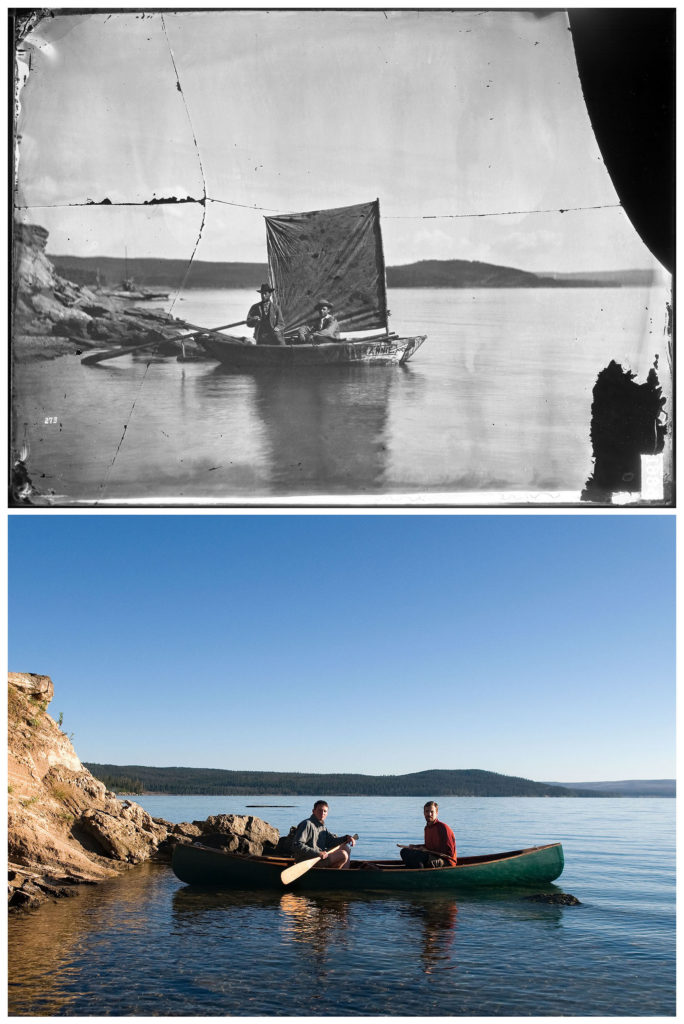

For the 1871 Hayden Survey, William Henry Jackson took photographs throughout Yellowstone. Between 2011 and 2013, Jackson, Wyoming photographer Bradley Boner traveled around the Park and re-shot nearly every image taken by Jackson.

Jackson’s photos—along with watercolors by artist Thomas Moran—are often credited with helping convince Congress to pass the Yellowstone Park Act in 1872, establishing the world’s first national park.

Boner, a photographer at the Jackson Hole News & Guide, set out from Paradise Valley north of Gardiner to the southern arms of Yellowstone Lake, to locate the exact location from which Jackson took his now-historic photos and to re-shoot his own images from those same points.

The result is more than 100 before-and-after photos captured in Boner’s book, Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time, a beautiful, large format coffee table book published in 2017 by the University Press of Colorado.

Working from historical documents, journals, Jackson’s notes and other sources, Boner identified 110 shots. He believes there are two other pictures taken at Crystal Falls, which is located between the Upper and Lower Falls, that he found mentions of but could never track down.

Some of the shots were relatively easy to reproduce because the locations became scenic overlooks—like Artist Point at the Lower Falls—once the park was developed for tourists with roads and hotels, campgrounds and other conveniences.

But for several other shots, Boner had to secure permission from park officials and be accompanied by a Park Service “chaperone” for get shots taken from areas that are now off-trail—near Mud Volcano, Mammoth, the Upper Geyser Basin and at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

At the Upper Falls, he had to scramble partially down the canyon with tourists nearby.

“There were parts of an old wire guardrail still down there,” he noted.

Meanwhile, his chaperone stood by to explain to tourists what Boner was doing and why he was allowed to be off the boardwalks in dangerous areas. Some tourists who saw him didn’t appreciate what they perceived as rule-breaking that could possibly damage a feature.

“Some of them were touchy,” Boner said—at least until they heard about his project and its historical significance.

The project took two years between 2011 and 2013. There were three months of research before he started taking photos. Boner hoped to complete the photography on weekends, but he quickly realized how impractical that was. Summer 2012, ended up scoring a seven-week leave of absence from his day job at the Jackson Hole News & Guide, which included a 10-day canoe trip around Yellowstone Lake (as seen above.

Boner made himself a photo album for his field work, an 11x 14 spiral notebook with good, high-resolution copies of Jackson’s images. It was often a simple matter of getting in the vicinity of the shot and lining up the horizon to match the Jackson photo and then matching up objects in the foreground. Some scenes were changed by modern intrusions like roads and power lines, but some were as wild as in Jackson’s day. For one particular image, Boner recalled, he looked down and saw something that gave him goosebumps.

“One time I found a bowling ball-sized boulder, and the lichen was the same as Jackson’s photo,” Boner said. “When everything just clicks in like that, feeling as if I were standing exactly where Jackson stood with his giant camera, it was almost like a window into the past, seeing exactly the same thing Jackson saw.”

Boner said people asked him why he shot in color rather than black and white, like Jackson. Boner said he wanted his photos to have a modern feel, plus Jackson would have used color himself had it been an option in 1871.

And in 1871, with photography still relatively in its infancy, camera gear was BIG. Jackson’s gear included a large box camera, a tripod, glass plates, chemicals and a “dark tent” that functioned like a darkroom. It took a mule to carry all of Jackson’s equipment.

Conversely, Boner carried a digital 35 mm camera in his daypack.

Jackson lived just shy of a century, from 1843 to 1942. In his excellent autobiography, Time Exposure, we learn that Jackson fought in the Civil War and lived to ride in an airplane (as seen below, on an American Airlines flight with Yellowstone Superintendent Edmund Rogers). Boner tells a story of Jackson visiting Yellowstone later in his life, seeing the park just like a tourist.

“There’s a picture of him with the Lower Falls in the background, and he’s using a 35 millimeter camera,” Boner said. “I can’t help but wonder if he thought ‘If only I’d had this 70 years ago.’ And I wonder if he was thinking, when he saw people taking pictures, just clicking and turning away, ‘You have no clue.’”

Having completed his book, Boner said he doesn’t have another photo project planned because he and his wife are busy raising two small children.

“They’re my project right now,” he said. “I look at these pictures and I take a lot of comfort in knowing that if we keep doing it right, my kids will be able to see Yellowstone the way I did as a kid. Maybe 100 years from now my grandkids and great-grandkids will see the same things I did. And who knows? My kids may do the same the project all over again.

“The whole mission of national parks is about preserving these things for future generations. I believe, as it’s said, these wild areas don’t really belong to us—we’re just taking care of them for the people who come after us.”

—

Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time is available online at https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/3053-yellowstone-national-park in various formats. Initial funding came through a $20,000 Kickstarter campaign, for which Boner expressed thanks to all who contributed.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.