A study of two forest plots just south of Yellowstone National Park portends very different futures for Yellowstone’s forest composition.

According to the New York Times, scientists studying two plots in Grand Teton National Park (dubbed “Densetown” and “Stumptown,” owing to their relative tree density) concluded that, with summers getting longer and drier, lodgepole forests may have trouble adapting.

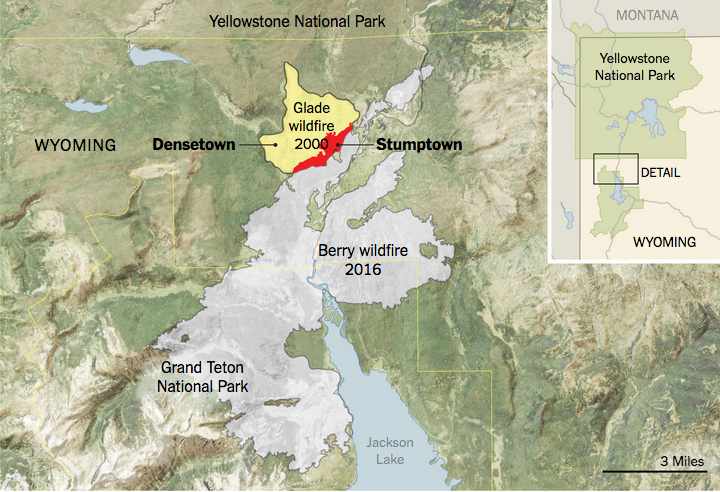

Densetown and Stumptown were previously burned by a wildfire in 2000. Last year, Stumptown got singed by the Berry Fire, which temporarily closed Yellowstone’s South Entrance. Densetown was untouched. You can see a map of both “towns” below, courtesy of the NYT.

According to the NYT, Densetown bounced back as well as expected from the 2000 fire, with many young lodgepole pines bursting up. Lodgepoles rely on fires to release seeds and spur the growth of new trees. Stumptown, however, burned by Berry, may not fare so well. From the NYT:

Although lightning-sparked fires are a natural part of the forests’ life cycles, forests reburning at short intervals is a relatively rare phenomenon. For the past 10,000 years, these woods have burned approximately every 100 to 300 years, meaning fires typically scorched old trees. But as climate change leads to longer and hotter dry seasons, younger forests throughout the Yellowstone region may start burning more frequently. (The jury is still out on how climate change will affect wildfires in other Western conifer forests.)

“If that becomes the norm, where there’s no time for these forests to take a break, to grow for 150 years or so without burning, you could see some widespread changes to the forests,” said Richard Hutto, an ecologist at the University of Montana.

These changes could play out in a couple of ways.

First, short-interval fires could overwhelm an evolutionary adaptation that in the past allowed burned lodgepole forests to regrow just as thickly as before. Many of the lodgepoles here are serotinous, meaning they grow pine cones sealed with a sappy resin that protects their seeds from flames. During a fire, the cones open and the seeds are released. Only mature lodgepoles produce these resinous cones, while younger ones yield unprotected cones that release their seeds as soon as they’re finished growing.

When fires are infrequent, the forest has time to mature and build up a stock of serotinous cones that will restart the next generation: hence Densetown. But when part of the young forest burned again just sixteen years into its regrowth, creating Stumptown, it had not yet produced many serotinous cones. Its seed stock was obliterated.

In the aftermath of the Berry Fire, researchers spent the summer counting seedlings around Stumptown, which proved somewhat difficult, as there were fewer trees to be found.

Besides charring old trees and spreading seeds, fires also provide food for ungulates like elk and habitat space for birds. Dr. Hutto reports, however, that birds don’t always flock to the remains of younger forests.

Fire ecologists and silviculturists have studied Yellowstone’s forests for decades; recent inquiry has focused scars left by the 1988 fires, some of which were burned in the 2016 Maple Fire. Understanding how fire scars reburn can help ecologists understand both forest and fire dynamics, which are best understood in tandem. Understanding the regrowth of trees after the 1988 fires has also helped researchers understand vulnerability to bark beetle outbreaks in western forests.

According to ecologist Brian Harvey of the University of Washington, speaking to the NYT, fires often leave small islands of unburnt trees, which are an important source for seeds. Dr. Harvey, however, says that more frequent and more “homogenous” fires could mean “fewer islands of unburned areas,” which means fewer seeds.

Researchers note that, as fires become more frequent, leaving shorter intervals for forests to regrow, tree composition often changes. Stumptown, for instance, became home to more aspens following the 2000 fire; 2016 saw aspens resprout after the Berry Fire.

Historically, according to the NYT, Yellowstone’s forests have tended to act like Densetown. However, with climate changing and forest composition altering, it’s possible dense stands of lodgepole may no longer be the norm. According to Dr. Monica Turner of the University of Wisconsin, more frequent fires doesn’t mean forests will go away. However, said forests “will be sparser than before.”

Yellowstone vegetation specialist Roy Renkin told the NYT he doesn’t believe younger forests will burn more frequently just because summers are warmer and drier, calling it “linear thinking” that doesn’t hold up to analysis.

Dr. William Romme, a forest fire researcher for Colorado State University, says the biggest change Stumptown portends is that forest fires won’t behave like they did before—which carries sobering implications.

Dr. Turner argues even though Stumptown doesn’t look like your average Yellowstone forest, it’s still a forest and more resilient than at first blush. “It will still be Yellowstone,” Turner argues.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.