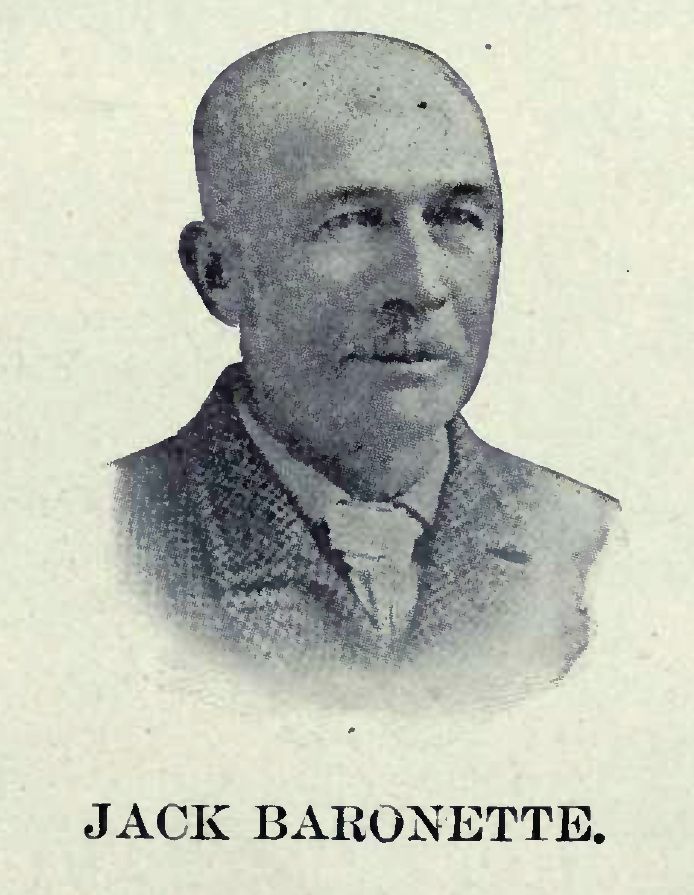

The namesake of Baronette Peak – early Yellowstone National Park character John “Yellowstone Jack” Baronett.

John “Yellowstone Jack” Baronett was an early park character. And yes, his name is spelled differently than the peak that bears his name: Baronette Peak, located in the Park’s northeast corner, about seven miles west of the Northeast entrance. Yellowstone Place Names author Lee H. Whittlesey accounts for the discrepancy, writing that members of Hayden’s third survey named the peak for him in 1878 and spelled his name incorrectly. But their version is the one that stuck.

Baronett was born in Great Britain in 1829 and lived a truly swashbuckling 19th century life, according to accounts compiled primarily from old Park County, Montana newspapers by Livingston historian Doris Whithorn in her self-published booklet, Twice Told on the Upper Yellowstone, Vol. 2.

Baronett was a seaman, a gold prospector, a Confederate scout during the Civil War, and a scout for General Custer in 1868. But for Yellowstone’s purposes, he’s best known for two achievements during his time in the park. One, he built the first bridge across the Yellowstone River, not far from Tower Junction, in 1871, planning to charge a toll; and two, he was renowned as the man who discovered Truman C. Everts, who had become lost from the 1870 Washburn Expedition.

The Everts story is still known around the park. The Washburn Party, a mixture of military and prominent Montana men, explored the park in 1870 after decades of mostly unproven rumors reaching the outside world of the majesty and strange features of the upper Yellowstone River. One of their members was Helena resident Truman C. Everts. Everts was somehow separated from the group south of Yellowstone Lake, and somehow managed not to stay lost for 37 days, despite the group searching for him and even leaving notes and food caches they hoped he would find.

Everts eventually began to follow the Yellowstone River downstream, according to an account Whithorn republished, “Thirty-nine Days Lost in the National Park, Chronicles of the Yellowstone,” by E.S. Topping, published in 1883.

Everts survived on thistle roots (the thistles eventually renamed Everts thistle inside Yellowstone) and the occasional fish, if he could stand to eat them raw as he had lost all his means of building a fire. First he lost his matches, but he was able to coax a spark using his glasses like a magnifying glass. But then he lost his glasses. He was able to maintain a small spark of fire and carry it with him for several days, but it eventually failed.

Baronett discovered Everts on what is now called Rescue Creek—in his honor—not far from Gardiner. Baronett and another man managed to help him to a nearby cabin after first ministering to him at a camp where they found him until he could be moved.

Everts feared his digestion was ruined by a mass of thistle in his digestive system, but Everts and his companion, George Pritchard, had the solution: they fed Everts a pint of bear fat rendered from a recently killed bear. And it did the trick.

Then in 1871, a year before the area was set aside as the world’s first national park, Baronett built a bridge across the Yellowstone River. The bridge spanned the river not far upstream from its confluence with the Lamar River. Gold had been discovered in Cooke City, and the route through the park and across Baronett’s bridge was a popular one.

He had hoped to make back the money it cost to build it by charging a toll. Whithorn’s research states the government later bought him out of his bridge interest for $5,000, which apparently didn’t even cover the expense of transporting the materials to the site and constructing the bridge.

The bridge was nearly destroyed in 1877 by Nez Perce Indians fleeing pursuit by the U.S. Army as they sought a new home, eventually hoping to settle in Canada. They were caught and surrendered in Montana’s Bear Paw Mountains, about 40 miles from the Canadian border. It was this battle and surrender where Chief Joseph said, “From where the sun now sets, I will fight no more forever.”

Baronett eventually settled in Livingston, where he died in 1906.

A tribute in the Livingston Enterprise, “Death of an Old Timer,” dated Dec. 1, 1906, had this to say about Baronett.

“Baronett was one of those hardy, rough-and-ready characters of the pioneer days of the great west. His adventurous spirit kept him constantly on the lookout for new fields of labor, and he pursued with much vigor the various propositions that enlisted his attention until the lapse of time laid its withering hand upon him, when he sought to take less arduous duties, at last finding a home in the Park County retreat.”

Baronett is buried in Livingston’s Mountain View Cemetery.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.