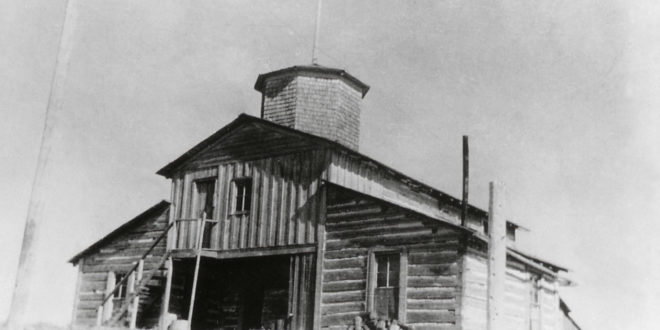

Before Fort Yellowstone came to be in the Mammoth area, the seat of power in Yellowstone National Park lay in another structure: the Norris blockhouse.

Built under the watch of Philetus W. Norris, Yellowstone’s second superintendent (1877-82), the blockhouse had two primary functions, according to Yellowstone historian Lee H. Whittlesey, writing in a book about Fort Yellowstone. First, it was built to withstand any potential attacks from the Nez Perce, who fled through the park following the summer 1877 Nez Perce war. Second, it brought a semblance of order to proceedings in Yellowstone National Park.

Indeed, the period between Yellowstone’s establishment (1872) and the arrival of the U.S. Cavalry (1886) was the worst in terms of “bad behavior.” In Searching for Yellowstone, Paul Schullery outlines how Yellowstone, like many western regions, became the site of “profligate slaughter of western wildlife resources” between 1865 and 1880, which coincided with novel tanning techniques and a market hungry for meat and hides. He also notes what Norris saw of the slaughter, which no doubt informed his opinions later as superintendent:

The historical evidence indicates that hide hunting was rampant in the park area for much of the 187s. The park’s superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, had essentially no budget and no support staff. He visited the park only briefly now and then, so we are dependent upon the accounts of visitors for our knowledge of the slaughter. Most visitors—at least the ones who wrote about their trips—came in the summer, missing the worst of the killing, which took place in winter or spring.

But in one year, 1875, a fortuitous combination of visits provides us with a glimpse of the park’s worst decade. Philetus Norris, who would two years later become the park’s second superintendent, made his second visit to the area in July (in 1870 he had gotten as far as the slopes of Electric Peak, along what would become the park’s north boundary, but unseasonably high water in the streams had almost drowned his guide, Fred Bottler, and they had had to turn back). This time he made it through the park and was appalled to discovered the destruction under way. In an unpublished memoir he described it:

The Bottler Bros. assure me that they alone packed over 2,000 elk skins from the forks of the Yellowstone, besides vast numbers of other pelts, and other hunters at least as many more, in the spring of 1875. As the only part of most of them saved was the tongue and hide, an opinion can be formed of the wanton, unwise, and unlawful slaughter of the beautiful and valuable animals in the Great National Yellowstone Park.

Norris built his blockhouse in 1879, according to Whittlesey:

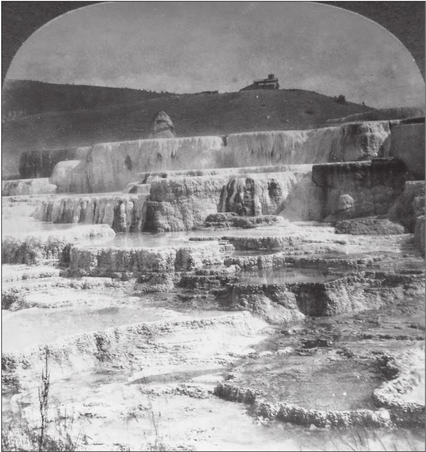

Sitting high atop Capitol Hill, the blockhouse afforded Norris the security of a 360-degree vantage point of Mammoth Hot Springs. From here, Norris would produce some of the park’s earliest official Reports to the Secretary of Interior, in which he cataloged his monumental efforts to undertake road and building construction and to studiously investigate the park’s human and natural history.

Norris did not remain long in Yellowstone National Park. Ousted in 1882 after ostensibly trying his hand at “political maneuvering,” Norris blockhouse remained part of the Mammoth scene for several decades, even as the Army started construction of Sheridan Camp, which became Fort Yellowstone.

In time, the Norris blockhouse, a remnant of Yellowstone’s wilder past, had served its time. According to park files, crews razed it in 1909.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.