A new report from the University of Montana paints a stark picture of overcrowding in national parks like Yellowstone.

According to the Missoulian, Norma Nickerson, director of UM’s Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research in the College of Forestry and Conservation, recently published a report in Montana Business Quarterly, “Montana’s Crowded Parks,” which evaluates the short-term spike in visitation and its deleterious effects on places like Glacier and Yellowstone National Parks—and offers potential solutions going ahead, should visitation continue to mushroom.

2016 saw a bevy of bad tourist behavior in Yellowstone National Park. Indeed, the antics of those four men from High On Life, who were either convicted or took plea bargains after walking on Midway Geyser Basin, are still fresh in the minds of Yellowstone residents and enthusiasts. Or when a 23-year-old man died after venturing hundreds of yards off the boardwalk in Norris, falling and dissolving in a hot spring.

And don’t forget about the bison debacle, where a tourist picked up a red dog after it was separated from its herd, leading to rangers having to put the bison down. Or the time a tourist was fined $1,000 for walking on Mammoth Terraces to collect thermal water. But the effects go beyond bad behavior. From the Nickerson report:

According to Ryan Atwell, Yellowstone National Park social scientist, “Yellowstone National Park has been experiencing steady growth in visitation over the past decade, topped off with a dramatic increase of 17 percent from 2014 to 2015 and even high levels of visitation in 2016, the centennial year of the National Park Service The park has not seen growth of more than 10 percent in over 25 years, so this dramatic short-term increase has shocked the park’s current systems. We do not yet have a clear understanding of what is driving this growth, but suspect that retirement of baby boomers and international travel may both be playing a part. Given long-term trends in visitation, we believe that demand for Yellowstone experience is likely to continue increasing over decadal time frames.

Increased visitation is taking its toll on daily operations. In 2015, (with visitation up 17 percent) motor vehicle accidents with injuries were up 167 percent. Search and rescue incidents were up 61 percent. Emergency medical responses were up 37 percent and Life Flight evacuations were up 25 percent.

These statistics parallel those of a city, but within a national park. The resource management side has an entirely different set of challenges for those visitors. Results from Yellowstone National Park researchers observing people in Yellowstone on four separate days this past summer showed that 226 total visitors were seen off the boardwalk/trail systems in Norris Geyser Basin between 9:30 a.m. and 3 p.m, equating to an average of one person every six minutes ignoring the regulations. This compares to 128 violations at Old Faithful and six violations at Midway Geyser Basin in four days.

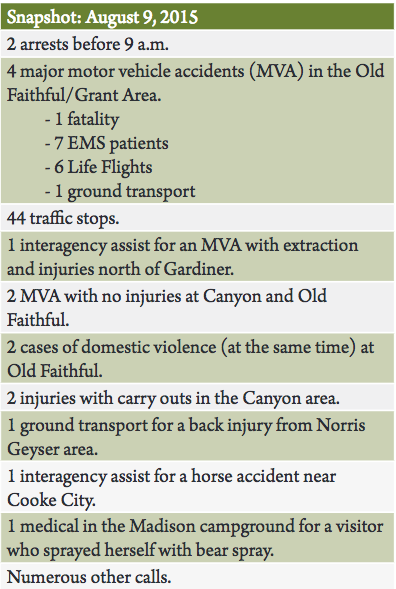

The report also includes a “snapshot” of statistics dealing with medical emergencies, accidents, and arrests in Yellowstone, seen below.

In addition, the report also notes how increased visitation has stressed water and sewer facilities in gateway communities like West Yellowstone. The report also notes the increase in economic takeaway for said communities.

Concerns over overcrowding have percolated throughout the National Park Service; Yellowstone Superintendent Dan Wenk has said his staff “learned a lot form the summer of 2015,” but warns that record crowds could continue to stress Yellowstone’s infrastructure. Indeed, Yellowstone, like other national parks, have considered setting visitor caps or other measures to cut down on congestion.

After walking through numerous problems associated with overcrowding, the report shares ways that parks like Yellowstone could alleviate visitation issues. Interestingly, none of the suggestions involve capping visitors. Rather, Nickerson emphasizes the ability of managers to “set the tone” for visitors and notes that most visitors care about quality, not quantity, when it comes to their fellow travelers:

In areas such as the front country in parks or highly developed recreation sites, one researcher suggests that management of crowding should focus on “limiting rude, depreciative and dangerous behavior” rather than trying to preserve certain types of psychological experiences. it does appear that people who act in disorderly ways (e.g. littering, getting too close to wildlife, loud voices or other detrimental environmental impacts) bothered other visitors more than the number of visitors. This suggests some possible solutions: 1) More ranger “boots on the ground” for educational and control purposes; 2) a new way of educating visitors before entering the area, or 3) additional fines to visitors.

[…]

Since crowding is site- and visitor-specific, it seems logical that managers of parks and outdoor recreation areas be allowed to enact management techniques as they experience visitor behavior becoming unacceptable and environmental conditions deteriorating. These managers know their landscape and situation better than most and should be able to decide what is good for the land and what may work for most people. Surveying visitors about trade-offs is one way to get the management decisions started. Other possible ways to determine limits is to assess the capacity of the current infrastructure.

The report also suggests that rangers find the way to “share the love” with other attractions, such as the National Bison Range and the C.M. Russell Wildlife Refuge. The report notes, however, that since it’s “not possible to increase the number of geysers” around the Park, managers might be limited in terms of alternate experiences they can advertise.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.