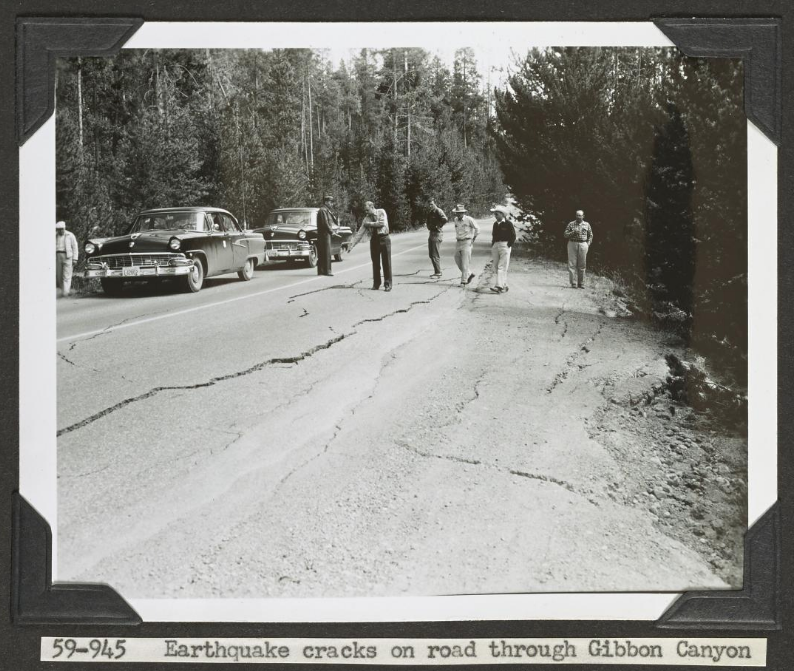

The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake, all 40 seconds of it, was a defining moment in Yellowstone National Park’s history.

Its effects were felt by features such as Bath Lake and Sapphire Pool and its ravages are still apparent in the landscape—most notably in the formation of Quake Lake, nonexistent before 1959, shown below. In addition, the quake racked up $11 million in damages and cost 28 people their lives. It’s still the most severe quake to affect the Rocky Mountain region.

Despite its prominence in the area’s history, however, there has been an apparent lack of writing on the subject, outside summaries and books discussing the earthquake’s technical aspects. One volume seeks to fill out that gap by offering a less technical, more general survey of the quake.

Indeed, readers curious about the Hebgen Lake quake who don’t want to bog themselves down with seismographic discussions should turn to The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake by Larry Morris, which, per Park Historian Lee H. Whittlesey, who wrote the forward, promises a “high-adventure chronicling of human drama.”

That being said, the minutiae is still useful. Of equal use to the main narrative are the two appendices Morris includes: Appendix A, which recounts the number of people evacuated from the site of the quake; and Appendix B, which relates technical information regarding the quake. Neither are necessary to enjoying the body of The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake, but essential for understanding. Appendix B, for instance, reproduces a summary from the U.S. Geological Survey that accurately (and drily) summarizes the massive impact of the quake on both Hebgen Lake and its environs, especially the landslide:

The slide mass dammed the Madison River, creating a lake which rose rapidly and attained a maximum depth of 190 feet just above the slide on September 10, [three and a half] weeks after the slide occurred. The surface of the slide mass was extensively altered by the Corps of Engineers, US Army, in an unsuccessful attempt to control the overflow of the new lake at its maximum height. This proved impossible because the gradient of the outlet channel across the slide mass was too steep and the flow too large compared to the erodability of the slide debris. The overflow rapidly eroded the lower end of the channel, and the spillway had to be cut down about 50 feet to a level where the channel appeared to be stable.

For comparison, here is an example of the tone Morris takes when describing the slide and other hazards from the quake. In this passage, Morris describes camper Ruby Armstrong’s experience in the first moments of the quake, as she searches for her family:

Ruby said the first sign of the quake sounded like a plane barreling down from overhead. “I kept thinking, ‘This is the end’ and then saw a tremendous mass of dirt,” she added. “I guess I started to run, and suddenly I was knocked off my feet and rolled and rolled. Then I was swept into the water and began to climb and climb over rocks. I thought I had lost my husband and children. Again and again, I screamed my husband’s name and thought it was no use. Then all of a sudden I heard him calling my name. He said the children were OK.”

Although Morris focuses on the immediate scene of the quake, he also includes some firsthand accounts of how the quake affected Yellowstone National Park—in particular its thermal features and visitor facilities:

“I was at the Old Faithful Lodge [in Yellowstone National Park] with my wife, two children, and a neighbor girl,” reported John D. Sanders of Salt Lake City. “We were watching a beauty contest with about five hundred people when the quake hit. We all ran outside and headed back to the motel. When we got there we saw people jumping out of windows wearing towels and bathrobes. Water was spurting from broken pipes. We sat in the car all night, and it kept shaking every now and then. It was the most terrifying experience we’ve ever had. Old Faithful was spouting very hard, and we thought the whole ground around us might blow up any minute.

National Geographic summed up what happened in Yellowstone Park when the quake hit: “The peaks trembled, rockfalls cascaded across roads, and steaming geysers, mud volcanoes, and boiling-hot pools erupted simultaneously in unseen splendor.

The way Morris rattles off people, accidents, and injuries, in succession, reveals his account’s strengths and limitations. On the one hand, the abrupt panning various earthquake victims—each enmeshed in their own dramas—rather accurately recreates what it was probably like to be on the scene: wild, chaotic, and frightening. On the other hand, of course, the barrage of names makes it very easy to lose track of which family, which unit you’re focusing on.

Key players emerge—such as Mildred “Tootie” Green, a registered nurse camping with her husband and son—and memorable incidents abound, but they rush by, sometimes leaving you cognitively breathless.

In fact, by the end of The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake, you might be left feeling like Tootie’s son Steve, who didn’t so much live through the quake as learn about it later:

Steve, nine at the time of the quake, never seemed to pay much attention to all the hubbub surrounding his mother. “All he could remember,” Tootie said, “was the helicopters and how big a deal that was.” Later in his life, however, without telling Tootie, he went back to the Madison River Canyon, saw the slide and the plaque and toured the Visitor Center and read the literature. Years later, he told Tootie about the visit. “Mom,” he said, “you did good.”

Nonetheless, The 1959 Yellowstone Earthquake lives up to the promise made in Whittlesey’s forward: an account “rich with human drama” and largely unencumbered by “the technical aspects of the quake.”

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.