July 1, 1923: President Warren G. Harding stood at Shoshone Point in Yellowstone National Park, and proposed to make history.

A month later, he was dead, and with it his monumental proposal for the Park.

Before we get to that proposal, however, we should start with the circumstances behind Harding’s visit.

First Presidential Visit Since 1903

Harding was familiar with Yellowstone National Park, having visited it on his honeymoon with his wife Florence in 1891. But the visit would be his last, since he died a month later. And in the immediate aftermath of Harding’s death (a period of mourning that gave way to scandal as the autopsy of Harding’s administration brought numerous corruptions to light) Harding’s final Yellowstone trip was forgotten by biographers.

However, according to Horace M. Albright, as narrated to Robert Cahn in The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-1933, Harding’s visit was important in more ways than one.

It was the first trip made by a standing President since Theodore Roosevelt visited the Park in 1903. It was also the first visit made after the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, which took over managerial duties of Yellowstone from the U.S. Army.

But most importantly, had Harding lived and made it to a second term, the Greater Yellowstone Area and the National Park System may have changed dramatically—for the better.

Teapot Dome Scandal

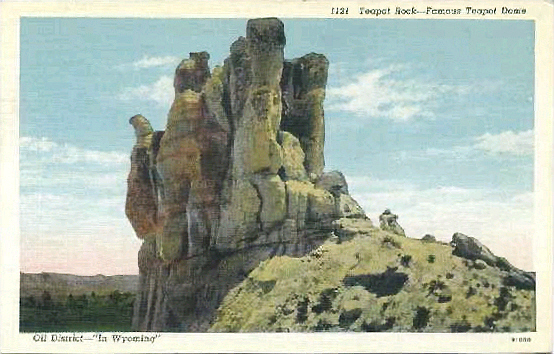

Before we get to the Hardings in Yellowstone, we should talk about the scandal that blighted (and to this day, still blights) Harding’s administration: the Teapot Dome Scandal.

For context: until Watergate, the Teapot Dome scandal was the most serious in the history of the presidency. And it intimately involved Wyoming.

Teapot Dome, pictured above, is a natural rock formation just north of Casper. It was the site of a “navel petroleum reserve,” where drilling was prohibited save in states of emergency. And (it should be noted) any oil drilled there would likely go to feed the Navy. In spite of the prohibition, many oilmen coveted the reserves and (it seemed) would do anything to get a crack at them.

Enter President Harding in 1920 and his new Interior Secretary, Albert Fall, who convinced Harding to transfer control of the naval reserves from the Navy to the Interior. With control established, Fall then accepted bribes and promised access to two prominent oilmen, Edward Doheny and Harry Sinclair.

The general consensus is that the President, while at fault for appointing Fall (reportedly a favorite at Harding’s personal poker table), did not comprehend the full implications of Fall’s activities. Indeed, he went to prison, the first U.S. cabinet member to do so.

Fall did resign March 4, 1923, and was replaced by Hubert Work, who would make an appearance with Harding in Yellowstone alongside Albright and Mather.

Health

It’s also important to note (briefly) the President’s health prior to his final Yellowstone trip.

Both Hardings were chronically ill throughout their lives—indeed, Florence died a little over a year after her husband—but the President’s health was especially capricious toward the end of his life, according to Robert K. Murray, writing in The Harding Era.

A chronic overeater and smoker who slept little, by 1919, Harding registered frequent complaints of chest pain. He reported sugary urine and high blood pressure as well. But it was in the very beginning of 1923 where the President’s health was really in absolute, seemingly irreparable decline. From Murray:

The flu attack which felled Harding in mid-January 1923 unquestionably was the triggering factor in the subsequent rapid deterioration in his health. One medical expert later claimed this flu attack was actually accompanied by an undiagnosed coronary thrombosis followed by myocardial infarction. Thereafter Harding did experience great difficulty sleeping at night. Arthur Brooks, the president’s personal valet, confided to Edmund Starling in the late winter that the president could not lie down because if he did he could not breathe.

The Voyage of Understanding

Harding’s declining health did not stop him from undertaking a cross-country trip (against the advice of his doctors) ahead of the 1924 election, where he would strive for a second term. Indeed, according to Samuel Hopkins Adams in The Incredible Era, Harding had a particular name for the trip:

The term, ‘voyage of understanding,” which President Harding had adopted as the slogan of his trip, was double-edged. He hoped to persuade the nation to understand him, his purposes and policies, his plans to be furthered in a second term. But also he desired for himself a better comprehension of what the people thought and expected of him.

For contrast, Harding ascended to the Presidency in 1920 promising a “return to normalcy” after the upheaval of World War I. Understanding was in order on both sides—whether Harding was elected as a safer bet than his predecessor Woodrow Wilson’s progressive ambitions, or whether he was a competent statesman in his own right, with vision and ability.

Indeed, Harding worked extensively to make himself understood on this trip. According to Murray, Harding’s western speeches (which ranged in topic from the railroad to agriculture to law enforcement to waterpower to social justice) were all but unprecedented. According to Murray, “no such series of presidential speeches again occurred until the fireside chats of Franklin Roosevelt.”

Visiting Yellowstone

According to Albright, NPS Director Stephen Mather, having learned of Harding’s voyage, used his clout to get Harding to visit not one but three national parks (including Zion and Yosemite) on his trip, something Mather and Albright viewed as a coup for the agency. Indeed, while Harding had visited Yellowstone during his honeymoon, “As President, he had not expressed much interest in national parks, although he had been helpful on several matters.”

Indeed, in the early months of 1923, Harding established several National Monuments (Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, Hovenweep National Monument in Utah/Colorado, and May Pipe Spring in Arizona).

With the trip established, Albright and his contemporaries toiled long and hard to get ready for the President’s visit. Not only did they have to show off the Park to a President who hadn’t seen it since the days of stagecoaches, they had to show off the National Park Service, which was in its infancy as a government agency.

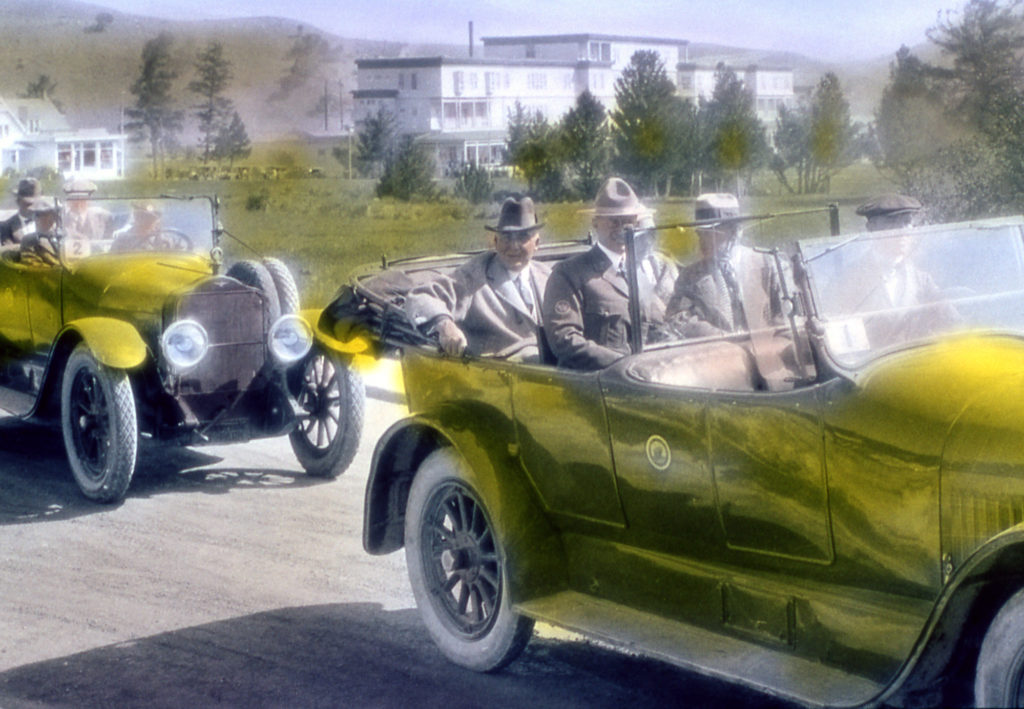

Indeed, the presidential party was a long way away from stagecoaches. The Hardings and Albright mostly saw the Park by touring car—a rather luxurious touring car at that.

From Mammoth to Old Faithful

Upon arriving, Albright escorted the Hardings into Mammoth Hot Springs, where they encountered a large crowd. Warren launched into full “meet-and-greet” mode, with newsreel cameras hard at work, whirring like locusts to broadcast the President’s visit.

After leaving Mammoth Hot Springs, President Harding turned to Albright and asked, pointedly, when they would see the next crowd. Albright informed him they would see no crowds—or cars—for a while. The road had been closed to traffic, for both security and (as Albright explains) personal reasons: Harding was to be given a private show of elk, deer, and other wildlife, without the fuss of cheering crowds and clicking cameras. Yet Harding was insistent.

Was he starving for attention? On the contrary, explains Albright/Cahn:

“Now, are you sure we are not going to see anyone?” the President repeated.

“I’m absolutely sure, sir,” I answered. “It will be twenty miles before we see another soul.”

Well, the President stuck his hand in his pocket and pulled out a package of tobacco, bit off a piece, and started to chew. He spat the juice over his shoulder, neatly clearing the side of the car. He continued enjoying his tobacco until we got near Norris Geyser Basin, where we saw that some people were gathered, and he hastily got rid of his cheekful.

No word on whether Harding appreciated any wildlife with his snuff.

In Old Faithful

After seeing Old Faithful erupt, Harding was persuaded by ranger Eivind Scoyen to make a walk down to Grand Geyser, which Scoyen hyped as twice as impressive as Old Faithful. Of course, Grand (however, well, grand) isn’t quite as accommodating in its eruption cycle, and despite Scoyen’s best estimate, the party had to wait over an hour, to Albright’s evident embarrassment. Luckily for Albright, Grand did go off—to the eminent pleasure of President Harding.

Afterward, the Hardings made their way to the Old Faithful Inn for dinner and bed. President Harding also shook hands with an estimated 500 people that night.

What Might Have Been

As mentioned, Albright had more than one mission during President Harding’s visit. He had to be an agreeable host, but he was also lobbying for the Service’s purpose. Indeed, Albright had a vision for Yellowstone, and he made a point of sharing it with Harding. That vision was southward, looking toward the Tetons.

We may take for granted the existence of Grand Teton National Park, Yellowstone’s craggy, verdant neighbor just to the south. We may also take for granted their relative continuity. Indeed, it’s as if they were one Park, not two with a connecting parkway. It wasn’t always so.

Recall that while Yellowstone was established in 1872, Grand Teton didn’t come into being until 1929—after decades of passionate lobbying and decades of equally passionate opposition. Albright’s ambition, and the centerpiece of his pitch to President Harding, was simple: incorporate the Tetons and the surrounding forests into Yellowstone National Park.

He pulled out all the stops, as it were, to get Harding to agree, taking the President out to Shoshone Point to let him see the Tetons. He plied the President all along the way, filling his ears with picturesque descriptions of Jackson Hole, adding that his dream of extending Yellowstone’s claim southward had been shot down in Congress.

In a sense, Harding was a captive audience, but this was a “voyage of understanding,” after all. And Harding had a particular understanding, according to Albright, as he looked out from Shoshone Point, where “the weather was perfect and we could see for forty miles,” especially the Tetons capped with snow in the early morning. From Albright/Cahn:

Harding was impressed. He gazed silently at the view, obviously moved, then turned to me and said, “I’ll get busy on that extension legislation when I get back.”

“You’ll have a lot of trouble,” I warned. “There’s a lot of opposition in Wyoming to the idea of putting the Tetons and the Jackson Hole into the Park, and it could hurt you politically.”

“It’s worth the trouble,” he shot back. “We can do it.” With the newspaper reports and cameras close by, recording it all assiduously, the President announced that he fully supported the plan to add the Tetons to Yellowstone National Park.

Feeding Bears

Heading out from Shoshone Point toward Yellowstone Lake, according to Albright, the President seemed more interested in having “a day off” after promising the fulfillment of Albright’s brightest hopes and dreams. And Albright was happy to oblige. At the top of President Harding’s wishlist? Feeding bears.

Bear feeding was a common practice in the early history of the Park, especially from the 1890s through the 1920s. Indeed, bear feeding was not banned until the late 40s—though it undoubtedly continued.

In particular, Harding was interested in seeing “Jesse James,” so named because he would appear by the roadside and “hold-up” drivers. He got his wish as they approached Lake Village, tossing scraps to both Jesse James and another black bear. According to the White House Historical Association, July 1, Harding also fed “gingerbread covered with molasses” to a chained black bear cub named Max in the Lake area, shown in the picture above.

“I’m sorry, but it cannot be done”

Harding also expressed an interest in fishing—a fact that may have surprised people who knew that the President seemed more at home at a poker table than tying flies. Indeed, in their June 30, 1923 paper, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle opined that “Mr. Harding isn’t generally regarded as much of a fisherman and it is doubtful whether he will try his luck with the fly.” Albright offers a different version of the story, however:

When we got to Yellowstone Lake, President Harding wanted to know why we hadn’t made arrangements for him to do some fishing. I explained that the Secret Service had vetoed it because the park was unable to provide a boat fast enough to keep up with the one the President would use … Dick Jervis, head of the Secret Service detail, was sitting alongside our driver, and the President barked at him that he didn’t see why he couldn’t go fishing. “I’m on vacation and I want to enjoy myself,” he said. But Jervis gently said, “No, Mr. President, I’m sorry, but it cannot be done.” It was the first time I realized that where security is concerned, the Secret Service can overrule the President of the United States.

Arriving at Lake Hotel, President Harding was regaled by a group of college girls, who sang songs to the delighted President—but to the consternation of Florence (also known as “the Duchess” for her steely possessiveness of consort Warren), who chided Harding afterward: “Warren, it took you longer to say goodbye to those pretty girls than to run through several hundred tourists yesterday at Old Faithful!”

“A great possession for the United States of America”

To cap off President Harding’s visit, Albright escorted him to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. At Artist Point, with reporters and newsreel cameras in tow, Harding commented for all the world to hear: “There must be no interference with the flow of water through this canyon; such interference would destroy much of its beauty and majesty.”

He reiterated this theme in a brief speech at the Roosevelt Arch, with one point that especially stuck with Albright, where Harding pledged that “Commercialism will never be tolerated here so long as I have the power to prevent it.”

Harding’s whole speech at the Arch is remarkable, according Senator Robert Torricelli and Andrew Carroll, editors of In Our Own Words: Extraordinary Speeches of the American Century. Harding, whom H.L. Mencken whose rhetorical aplomb was equivalent to a “hippopotamus struggling to free itself from a slough of molasses,” nonetheless hit upon something when speaking about the Park. From Harding’s Arch speech included in In Our Own Words:

The Yellowstone Park is a wonderful place. It is a great possession for you of Montana and the other states which have territory therein. It is a great possession for those who live nearby. It is a great possession for the United States of America. I have been marveling at our experiences of the last two days. During that time we have seen literally a fine cross section of the citizenship of our land. I believe that during my brief sojourn in the park I have greeted personally travelers from every state in the American Union, and, in addition to that, I have had the privilege of greeting citizens of England, of Canada, and of Cuba. Manifestly all the country is beginning to turn its face toward the Yellowstone National Park, and I am glad of it, for there is nothing more helpful, nothing more uplifting, nothing that gives one a greater realization of the wonders of creation than a visit to that great national institution.

Untimely Demise

As Harding left the Park, Albright felt confident that his Grand Teton expansion would become a reality, and that the National Park Service would become a priority for the newly enamored president. Alas, it was not to be. President Harding passed away August 2, 1923 after a tumultuous July that brought him briefly to Alaska before the party was marooned in San Francisco by Harding’s illness. And with Harding’s death came the death of Albright’s grand expansion of Yellowstone. Although he would live to see Grand Teton dedicated in 1929, it wouldn’t be the way he originally planned.

Worst of all, for Albright, Harding died before making a presidential visit to Yosemite. As Albright relates to Cahn, “Not only had the nation lost a President, but the national parks had lost a valuable friend.”

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.