Located just west of Daisy Geyser, on the way to Black Sand Basin, Punch Bowl Spring has a long history with Yellowstone visitors.

Indeed, anyone with a passing knowledge of Yellowstone National Park’s early history (especially with regards to the procurement of souvenirs) may be surprised by the feature. By and large, the feature is unchanged in shape and function from when it was first named on the Hayden Geological Survey, in Dr. Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden’s “Twelfth annual report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories : a report of progress of the exploration in Wyoming and Idaho for the year 1878.”

Punch Bowl Spring consists of a raised bowl of sinter, bubbling with frothing liquid—of the sort you might expect at a Halloween party. It’s an apt comparison considering, at one point, Punch Bowl was called the “Devil’s Punch Bowl.” Further, one photo by H.B. Calfee listed the feature as the “Faeries’ Well.”

Early Assessments

As mentioned, Punch Bowl Spring drew acclaim from various travelers both professional and amateur. From the “Twelfth annual report of the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories:”

This handsome spring is 900 feet southwest of the Pyramid. It is remarkable for its crested rim, which rises 1 ½ feet above the general level. It is handsomely beaded and has a pointed border. A large area surrounding the spring is covered with siliceous deposit. [Theodore Bryant] Comstock found the spring active in 1873, and Captain [William] Ludlow says it played frequently during August 23, 1875. (See p. 28, Report of reconnaissance from Carroll, Mont., to Yellowstone National Park and return in 1875. We [the Hayden survey] have never seen it in action.

Indeed, rather than take Hayden’s word at face value, let’s look at Captain Ludlow’s account of The Punch Bowl:

Near by [Giant Geyser] are the “Grotto”, seen yesterday, and which played almost constantly during the day; the “Pyramid”, a cone of silica 25 or 30 feet high, with steam slowly escaping from it, but its life now nearly extinct; the “Punch Bowl”, and smaller ones. The last-named geyser played frequently during the day, some of its exhibitions being very fine.

Albert Brewer Guptill, in the 1899 Haynes Guide, had several glowing things to say about Punch Bowl as well—although he was somewhat skeptical of the claims, for whatever reason:

The Punch Bowl.—The wagon road leading westward from the Splendid [Geyser] toward Black Sand and Sunlight Basins, passes the Punch Bowl, by far the handsomest spring of its peculiar class to be found in the geyser region, if not in the world. Situated on the summit of a small mound of silicious deposit, some five feet above the general level, it is about ten feet in diameter, with a glittering rim of brilliantly colored formation eighteen inches in height. The constant boiling of its content, though only a small part of its surface is agitated, as the bubbles of escaping steam and gas arise, produces a wave-like undulation over the entire spring and gives it steady and not inconsiderable overflow. A small cave-like opening on the east side of the mound or cone is very handsome and much admired, having the appearance of being lined with satin of the rarest beauty and texture. Early visitors to the Park during the seasons of 1873 and 1875 speak of this spring as being an active geyser, and during 1888 similar reports gained currency. Nothing, however, is certainly known as to the correctness of these reports, though they are highly probable.

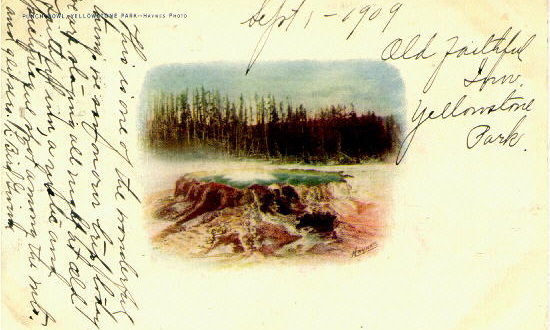

Punch Bowl Spring retained its allure with visitors, especially with the rise of Haynes postcards. Indeed, the picture at the top not only showcases Punch Bowl, but also contains contemporary testimony to the spring’s beauty: “This is one of the wonderful things we saw on our trip today. We are staying all night at old faithful inn, a rustic and picturesque spot among the mts. and geysers.”

“Expect poison from the standing water”

Of course, just because the Punch Bowl’s rim survived early attitudes didn’t mean it was left alone. Indeed, according to Lee H. Whittlesey in Yellowstone Place Names, starting around 1910, one of the Wylie Company camps piped waters for use in a nearby tentcamp.

And as to whether people drank from Punch Bowl Spring, no incidents spring to mind. In all likelihood, the picture above was done on a lark.

Of course, people did drink geyser water—much to their later regret. Indeed, William O. Owen (credited with being one of the first people to make a tour of Yellowstone by bicycle) relates an incident where he and his party decided to brew “geyser tea” after camping somewhere in the Upper Geyser Basin:

Returning to our camp a hasty dinner was prepared, connected with which is a little incident too good to go unsung. A brilliant idea seized me that a cup of tea made from boiling geyser water would be something to boast of at home. Accordingly the teapot was filled with geyser liquid, a handful of tea thrown in and in a few minutes the mixture was declared ready for use. The idea was so romantic and unusual that nothing short of three cups of this delightful beverage would appease me, although my companions were prudent enough to be satisfied with a much less quantity. In less than an hour I was visited with an attack of seasickness that even now makes me shudder to recall. The most violent retching and blinding headache, accompanied with vertigo, were the prevailing symptoms; and for a short time it seemed that one-third of the bicycle party would find a resting place in the Upper Geyser Basin.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.