President Theodore Roosevelt’s visit to Yellowstone in 1903 is an integral part to his mystique and legend.

Indeed, it helped provide the basis for one of his most interesting and radical positions: a new conservation ethic, closely wedded to his identity as an American statesman and citizen.

It was not the first time a standing President had visited Yellowstone National Park. President Chester A. Arthur visited in 1883, although he decidedly did not “rough it,” choosing instead to bring a long train of dignitaries and luxuries. In a sense, he was one of the first “glampers” in Yellowstone.

Further, it wasn’t the first time Roosevelt had visited Yellowstone, according to Douglas Brinkley in The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America. In 1890, he took a family vacation to the Park and found it overall delightful. Admittedly, however, he was disappointed he couldn’t see any big game out in the geyser basins—too many people.

Further, while he reportedly found the Park “had the same rejuvenating effect” as Baden-Baden (a great European spa), the trip took its toll on his family. In the first place, Roosevelt’s chosen guide, Ira Dodge, got them lost. And wife Edith was thrown from a horse, injuring her back badly. Roosevelt reportedly suffered from a “rather strained” groin for a few days, making horseback riding uncomfortable

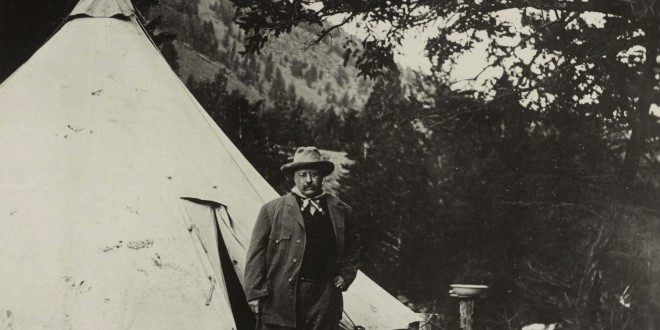

At any rate, as President, he wasn’t going to make the same mistake. Roosevelt wanted to “rough it,” and while some nights were spent in the Norris and Fountain Hotels, there were plenty of instances where the President and company camped, like the one shown below. He also took different traveling partners along. Rather than family, he traveled with army personnel, experienced guides, and (most notably) naturalist “Oom John” Burroughs.

A Grand Tour

Yellowstone was just one of the stops Roosevelt made in 1903. Indeed, it was a grand tour, taking Roosevelt to Chicago, north through Wisconsin, Minnesota and North Dakota. It must have been a grand sight watching the “Roosevelt Special” (a special six car operation—precursor to the modern motorcade) roll into the Gardiner Basin!

But while the train was impressive (complete with the Elysian car, a “rolling White House” for the President) Roosevelt left all that behind when he went into Yellowstone. The Elysian was unhitched in Cinnabar, Montana, left in the careful hands of secretary William Loeb, Jr.

The Trip

The Yellowstone trip lasted a little over two weeks, from April 8 to the 24th, when Roosevelt took the stage to dedicate the Roosevelt Arch. In that time, he, Burroughs, Major Pitcher, and suite of other people camped and tramped (to borrow from the title of a short book Burroughs published, detailing his time spent on the trip) around the Park, watching wildlife and visiting the geyser plains.

According to Burroughs, the geysers quickly bored the President, who felt more awestruck with the scenery and the wildlife. Just like on his 1890 trip. One gets this impression from Roosevelt’s account of visiting the Park, which was mostly dedicated to wildlife:

At Norris Geyser Basin there was a perfect chorus of bird music from robins, western purple finches, juncos and mountain bluebirds. In the woods there were mountain chickadees and pygmy nuthatches, together with an occasional woodpecker.

The trip was also marked by a rather unique solitude, according to Burroughs:

The President wanted all the freedom and solitude possible while in the Park, so all newspaper men and other strangers were excluded. Even the secret service men and his physician and private secretaries were left at Gardiner. He craved once more to be alone with nature; he was evidently hungry for the wild and the aboriginal,—a hunger that seems to come upon him regularly at least once a year, and drives him forth on his hunting trip for big game in the West.

Indeed, those newspapermen were left high and dry, so to speak, at pains to describe the President’s trip, which led to a few misunderstandings. In the midst of the trip, one rumor circulated that Roosevelt had shot a mountain lion while in the Park—a rumor that made it into The New York Times . This later turned out to be false, according to Brinkley, and though Roosevelt was reportedly “livid,” he felt loath to call out the Times, given their long association. The paper later published a clarification.

Other papers were quite rankled by the President’s decision to exclude the media, most notably the New York Morning Tribune, who ran this tidbit April 22, 1903: “President Roosevelt on his trip through Yellowstone Park did not fall into a canyon, was not attacked by a bear, was not showered with hot liquid from a geyser, and was not almost lost in the snow. The President needs a new press agent.”

Roosevelt did kill in the Park though: while riding toward Fountain Hotel, Roosevelt reportedly jumped from a stagecoach and scooped up a field mouse—giddy that it might be a new species. Alas, while the specimen (Microtus nanus) was new to the Park, it was not new to the taxonomic record.

“Who Is Laughing Now, Oom John?”

What’s interesting about Roosevelt’s Yellowstone trip in 1903 is how it balanced work with play. It was a hugely important time, one year before reelection, after a shocking assassination ushered him into the Presidency. It was politically useful for Roosevelt to be making the rounds and firmly establishing a platform through practice (something he was long accustomed to) but, as Burroughs notes, the Park also offered him he rather needed: respite.

Although there was respite, there was no rest. Roosevelt and company had a jam-packed schedule, camping throughout the Park, traveling the geyser basins by sleigh, as the snow was rather thick. Roosevelt and Burroughs even found time to go skiing outside the Norris Hotel, which produced a rather memorable moment in Burroughs’ recollection:

In front of the hotel were some low hills separated by gentle valleys. At the President’s suggestion, he and I raced on our skis down those inclines. We had only to stand up straight, and let gravity do the rest. As we were going swiftly down the side of one of the hills, I saw out of the corner of my eye the President was taking a header into the snow. The snow had given way beneath him, and nothing could save him from taking the plunge. I don’t know whether I called out, or only thought, something about the downfall of the administration. At any rate, the administration was down, and pretty well buried, but it was quickly on its feet again, shaking off the snow with a boy’s laughter. I kept straight on, and very soon the laugh was on me, for the treacherous snow sank beneath me, and I took a header, too.

“Who is laughing now, Oom John?” called out the President.

The spirit of the boy was in the air that day about the Cañon of the Yellowstone, and the biggest boy of us all was President Roosevelt.

Boy, naturalist, statesman, President: Roosevelt was each and every one of these things, and Yellowstone proved to be just the ticket to get him thinking ahead in his administration. Indeed, Roosevelt’s visit to Yellowstone with Burroughs is just as important as his visit to Yosemite with John Muir, in terms of the impact each made.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.