October 10, 1870: Truman Everts was found in Yellowstone National Park after being lost for over a month.

Today, Everts’ name lasts in the Park through Mount Everts (pictured below) and Everts Thistle, also known as elk thistle, which Everts famously subsisted on (in part) during his misadventure.

Everts’ rediscovery, after he was presumed dead, would become one of several remarkable events that occurred in the period leading up to the creation of Yellowstone National Park. It would spawn a celebrated article for Scribner’s Monthly (“Thirty-Seven Days of Peril”) and make Everts into a minor legend—something that still holds true today for anyone who wants to understand Yellowstone’s pre-park history.

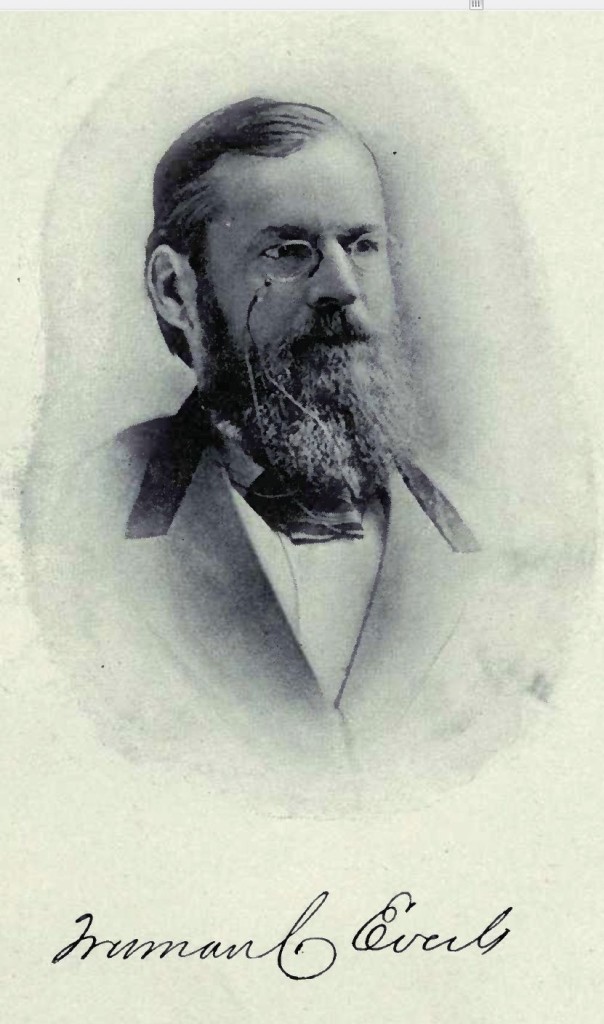

There was no indication Everts would end up having such a harrowing adventure. He joined the Washburn Expedition, coming off a stint as assessor of internal revenue for Montana, a position granted by President Abraham Lincoln. He was 54 years old, as shown in the picture below.

Now, things didn’t start out well for Everts. According to Langford’s Diary of the Washburn expedition to the Yellowstone and Firehole rivers in the year 1870, he fell sick Tuesday, August 23, 1870. After convalescing for a few days, he rejoined the expedition. September 9, 1870: Everts goes lost—the start of his troublesome 37 days.

Everts’ disappearance is a recurrent thread in both Langford’s diary as well as his later article in Scribner’s Monthly, “The Wonders of the Yellowstone,” written after Everts was found. Nonetheless, his disappearance makes for some suspenseful reading:

One of our comrades (the Hon. Truman C. Everts, late U.S. Assessor of Montana) had failed to come up with the rest of the company; but as this was a common circumstance, we gave it little heed until the lateness of the hour convinced us he had lost his way. We increased our fire and fired our guns, as signals; but all to no purpose. It had been a sort of tacit agreement among us only the night before, that should any one get parted from the company, he would at once go to the south-west arm of the lake (that being our objective point_ and await there the arrival of the train … If we had not continued our journey with all possible expedition towards the point indicated, Mr. Everts would probably have rejoined us within three or four days, as he has informed us since that he visited our camp, but the falling foliage of the pines had entirely obliterated our departing trail (118).

Langford would go on to add what turns out to be (in retrospect) a pretty canny advertisement for Everts’ own account, which would be published in the November 1871 issue of Scribner’s Monthly. Remember: Langford’s article came out in May and June of 1871:

The narrative of this gentleman, of thirty-seven days spent in this terrible wilderness, will furnish a chapter in the history of human endurance, expose, and escape as incredible as it must be painfully instructive and entertaining (118).

Everts would pay back Langford’s compliment in his own piece:

My friend Langford has so well described the scenery and physical eccentricities of the country, that I should feel that any attempt to amplify it would be to

“Gild refined gold and paint the lily.”

My narrative must, therefore, be strictly personal (1-2).

Everts maintained his horse was scared off while he was exploring—as was his prerogative, he would assert. The horse was carrying all of his supplies—including, most importantly, his blankets, gun, and matches. Everts also maintained, as he worked his way toward where he thought the party was, that he was in no serious danger. However, he became increasingly aware of his plight—nay, his danger.

Indeed, the expedition became disheartened day-by-day; they were fearful Everts had suffered some sort of calamity or had broken the “tacit agreement” the party made earlier, as Langford notes:

On full consultation we came to the conclusion he had either been shot from his horse by an Indian, or had returned down the Yellowstone, or struck out upon some of the head-waters of Snake River, with the intention of following it to the settlements (120).

Indeed, things did not bode well for Everts. Phyllis Smith, writing in Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley: A History, summarized Everts’ misadventure, an admittedly picturesque one:

Despairing of ever being found, Everts ate thistle roots and starting warming fires with the lens of his opera glass. On at least one occasion, exhausted and cold, he lay down near boiling springs to get warm, getting too close and scalding his thigh. A hallucinatory figure, he said later, gave him comfort and advice on staying alive (116).

Thistle roots made for a strong motif in Everts’ tale for Scribner’s Monthly, as a stand-in for manna during his harrowing plight:

While looking for a spot where I might repose in safety, my attention was attracted to a small green plant of so lively a hue as to form a striking contrast with the deep pine foliage. For closer examination I pulled it up by the root, which was long and tapering, not unlike a radish. It was a thistle. I tasted it; it was palatable and nutritious. My appetite craved it, and the first meal in four days was made on thistle-roots. Eureka! I had found food (4).

But it was no smooth sailing for Everts after this, as he reportedly had to seek shelter from a prowling mountain lion just after finding thistle and shelter. Then of course, after falling into a hungry slumber, uninjured by the prowling lion, he awakes to a numbing sleet storm. It seems Everts, lacking shelter and supplies, was done for, except for another “Eureka!” moment:

I could see no ray of hope. In this condition of mind I could find no better shelter than the spreading branches of a spruce tree, under which, covered with earth and boughs I lay during the two succeeding days; the storm, meanwhile, raging with unabated violence. While thus exposed, and suffering from cold and hunter, a little benumbed bird, not larger than a snow-bird, hopped within my reach. I instantly seized it and killed it, and, plucking its feathers, ate it raw. It was a delicious meal for a half-starved man (5).

More moments would follow, such as when Everts realizes he could “get fire from Heaven” using those conveniently retained opera glasses (6). As time went on, however, things got worse and worse for Everts, as he sustained thermal burns and frostbite, to say nothing of the hallucinations Everts started suffering:

More moments would follow, such as when Everts realizes he could “get fire from Heaven” using those conveniently retained opera glasses (6). As time went on, however, things got worse and worse for Everts, as he sustained thermal burns and frostbite, to say nothing of the hallucinations Everts started suffering:

An old clerical friend, for whose character and counsel I had always cherished peculiar regard, in some unaccountable manner seemed to be standing before me, charged with advice which would relieve my perplexity. I seemed to hear him say, as if in a voice and with the manner of authority:—

“Go back immediately, as rapidly as your strength will permit. There is no food here, and the idea of scaling these rocks is madness”

“Doctor,” I rejoined, “the distance is too great. I cannot travel it.”

“Say not so. Your life depends on the effort. Return at once. Start now, lest your resolution falter. Travel as fast and as far as possible—it is your only chance” (11).

Everts became more and more desperate, his dreams redolent with the finest food, from New York and Washington restaurants, or made by Everts himself, “[filling] range upon range of elegantly furnished tables until they fairly groaned beneath the accumulated dainties prepared by own hands” (12). And as time went on, the “clerical friend” left Everts all together; instead, Everts spent time talking to his various appendages and organs—arms, legs, stomach: “Each had his peculiar wants which he expected me to supply” (13).

Everts ended up ranging quite far during his 37 days. He reports making it all the way up to Tower Fall, and was found near The Cut, a canyon found west of Crescent Hill, according to Lee H. Whittlesey. By the end, he was in poor shape. A walking skeleton, bundled in parchment-like skin, it seemed all hope was lost for the poor assessor.

Everts was eventually found by a pair of trackers, George A. Prichett and Jack Baronett (“Yellowstone Jack”), who were in it for a $600 reward posted by friends of Everts in Helena, Montana. Everts maintained he found the pair when he felt a sharp reflection of “burnished steel” in his eyes.

Everts cut a startling figure before Prichett and Baronett: frostbitten, scalded, rather inhuman looking, according to George Black, writing in Empire of Shadows:

Everts cut a startling figure before Prichett and Baronett: frostbitten, scalded, rather inhuman looking, according to George Black, writing in Empire of Shadows:

It was Yellowstone Jack’s dog who actually found the missing explorer. Baronnet himself thought it was a black bear he saw shuffling along the hillside, and perhaps the burnished steel reflection seen by Everts was an indication that his rescuer was readying his gun to shoot the beast. Once he realized that it was not a bear, Baronett couldn’t decide what it was—certainly not a human being. Everts “was nothing but a shadow,” Baronett said later. “His flesh was all gone; the bones protruded through the skin on the balls of his feet and thighs. His fingers looked like bird claws” (333).

Purportedly, Everts weighed 55 pounds when the pair found him (Black maintains he weighed 90 pounds). Pritchett was dispatched to Fort Ellis for an ambulance while Baronett nursed Everts with bear oil, to assuage the wounds wrought by thistle in his stomach and his bouts of starvation.

Everts’ return was a triumph for the Washburn Expedition and the Montana Territory—a stirring story of frontier gumption. Accordingly, such a feat required a great celebration. From Empire of Shadows:

It took Everts a month to recover fully. But by the second week of November, General Washburn [leader of the Washburn Expedition] decided that the Assessor of Internal Revenue was well enough for an official celebration and invited the cream of Helena society to a gala banquet at the Kan-Kan, the fanciest restaurant in town, purveyor of Havana cigars, French cognac, and the celebrated K-K-K (”Kan-Kan Kocktails: Everybody Drinks Them”).

The elegantly furnished tables groaned like something out of Everts’s [sic.] fever dreams. Oysters, raw and roasted; twelve kinds of meat and six vegetable; three pies, three puddings. For dessert, fruitcake, pound cake, jelly cake, citron cake, jelly roll, jelly tarts, strawberry cream, puff paste, nuts, raisins, confections, and “rustar tart cream” whatever that might be. Even the fastidious Cornelius Hedges admitted that he had taken a little too much champagne.

There were speeches and toasts, of course. Everts himself said a few words, still a little frail and leaning on a walking stick (333-4).

Black adds that following this celebration and Everts’ recovery, there were grumblings and concerns. Someone purported Everts had killed the horse and subsisted on that until he ill-advisedly munched on elk thistle. And then there was the matter of reward: neither Pritchett nor Baronett saw a cent of their promised money. Hedges only begrudgingly reimbursed Baronett the cost of his supplies. Everts himself was reportedly ungrateful toward Baronett and Pritchett, maintaining he could have walked out of the wilderness just fine. Baronett, according to Whittlesey, grumbled to the Helena Independent in 1887 about how “he wished he had let the son-of-a-gun roam.”

Everts did roam of course—away from Yellowstone.

In his Scribner’s article, Everts wrote lavishly of Yellowstone’s virtues (in spite of his promise to Langford, he did “gild the lily” just a bit). Indeed, this is how Everts closed out his “Thirty-Seven Days of Peril,” with a lyrical evocation of Yellowstone:

In the course of events the time is not far distant when the wonders of the Yellowstone will be made accessible to all lovers of sublimity, grandeur, and novelty in natural scenery, and its majestic waters become the abode of civilization and refinement; and when that arrives, I hope, in happier mood and under more auspicious circumstances, to revisit scenes fraught for me with such thrilling interest; to ramble along the glowing beach of Bessie Lake; to sit down amid the hot springs under the shadow of Mount Everts; to thread unscared the many forests, retrace the dreary journey to the Madison Range, and with enraptured fancy gaze upon the mingled glories and terrors of the great falls and marvelous canon, and to enjoy, in happy contrast with the trials they recall, their power to delight, elevate, and overwhelm the mind with wondrous and majestic beauty (17).

In spite of this stirring tribute, Everts turned down an offer to be a superintendent in the Park later on—it carried no salary, though it likely would have afforded ample opportunity to “revisit scenes fraught for [him] with such thrilling interest.” He would end up passing away in Maryland, just over 30 years after his ordeal, according to Langford in his diary:

Mr. Everts died at Hyattsville, Md., on the 16th day of February, 1901, at the age of eighty-five, survived by his daughter, Elizabeth Everts Verrill, and a young widow, and also a son nine years old, born when Everts was seventy-six years of age,—a living monument to bear testimony to that physical vigor and vitality which carried him through the “Thirty-seven days of peril,” when he was lost from our party in the dense forest on the southwest shore of Yellowstone lake (xviii-xix).

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.