We have a better working knowledge of the Yellowstone National Park geothermal system, with a newly discovered, deeper magma reservoir feeding the shallower, long-known magma chamber close to the Earth’s surface.

This deeper reservoir, as determined by University of Utah seismologists, would fill the 1,000-cubic-mile Grand Canyon 11.2 times, while the previously known magma chamber would fill the Grand Canyon 2.5 times, says postdoctoral researcher Jamie Farrell, a co-author of the study published online today in the journal Science.

“For the first time, we have imaged the continuous volcanic plumbing system under Yellowstone,” says first author Hsin-Hua Huang, also a postdoctoral researcher in geology and geophysics. “That includes the upper crustal magma chamber we have seen previously plus a lower crustal magma reservoir that has never been imaged before and that connects the upper chamber to the Yellowstone hotspot plume below.”

Contrary to popular perception, the magma chamber and magma reservoir are not full of molten rock. Instead, the rock is hot, mostly solid and spongelike, with pockets of molten rock within it. Huang says the new study indicates the upper magma chamber averages about 9 percent molten rock – consistent with earlier estimates of 5 percent to 15 percent melt – and the lower magma reservoir is about 2 percent melt.

So there is about one-quarter of a Grand Canyon worth of molten rock within the much larger volumes of either the magma chamber or the magma reservoir, Farrell says.

Yellowstone’s plumbing system is no larger – nor closer to erupting – than before, only that they now have used advanced techniques to make a complete image of the system that carries hot and partly molten rock upward from the top of the Yellowstone hotspot plume – about 40 miles beneath the surface – to the magma reservoir and the magma chamber above it.

“The magma chamber and reservoir are not getting any bigger than they have been, it’s just that we can see them better now using new techniques,” Farrell says.

NSF Yellowstone Discovery Video from The University of Utah on Vimeo.

Study co-author Fan-Chi Lin, an assistant professor of geology and geophysics, says: “It gives us a better understanding the Yellowstone magmatic system. We can now use these new models to better estimate the potential seismic and volcanic hazards.”

The researchers point out that the previously known upper magma chamber was the immediate source of three cataclysmic eruptions of the Yellowstone caldera 2 million, 1.2 million and 640,000 years ago, and that isn’t changed by discovery of the underlying magma reservoir that supplies the magma chamber.

“The actual hazard is the same, but now we have a much better understanding of the complete crustal magma system,” says study co-author Robert B. Smith, a research and emeritus professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah.

The three supervolcano eruptions at Yellowstone – on the Wyoming-Idaho-Montana border – covered much of North America in volcanic ash. A supervolcano eruption today would be cataclysmic, but Smith says the annual chance is 1 in 700,000. (That number isn’t actually based on science, but rather than averaging the time between previous similar eruptions.)

Before the new discovery, researchers had envisioned partly molten rock moving upward from the Yellowstone hotspot plume via a series of vertical and horizontal cracks, known as dikes and sills, or as blobs. They still believe such cracks move hot rock from the plume head to the magma reservoir and from there to the shallow magma chamber.

Anatomy of a supervolcano

The study in Science is titled, “The Yellowstone magmatic system from the mantle plume to the upper crust.” Huang, Lin, Farrell and Smith conducted the research with Brandon Schmandt at the University of New Mexico and Victor Tsai at the California Institute of Technology. Funding came from the University of Utah, National Science Foundation, Brinson Foundation and William Carrico.

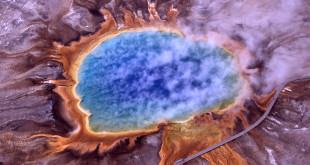

Yellowstone is among the world’s largest supervolcanoes, with frequent earthquakes and Earth’s most vigorous continental geothermal system.

The three ancient Yellowstone supervolcano eruptions were only the latest in a series of more than 140 as the North American plate of Earth’s crust and upper mantle moved southwest over the Yellowstone hotspot, starting 17 million years ago at the Oregon-Idaho-Nevada border. The hotspot eruptions progressed northeast before reaching Yellowstone 2 million years ago.

Here is how the new study depicts the Yellowstone system, from bottom to top:

- Previous research has shown the Yellowstone hotspot plume rises from a depth of at least 440 miles in Earth’s mantle. Some researchers suspect it originates 1,800 miles deep at Earth’s core. The plume rises from the depths northwest of Yellowstone. The plume conduit is roughly 50 miles wide as it rises through Earth’s mantle and then spreads out like a pancake as it hits the uppermost mantle about 40 miles deep. Earlier Utah studies indicated the plume head was 300 miles wide. The new study suggests it may be smaller, but the data aren’t good enough to know for sure.

- Hot and partly molten rock rises in dikes from the top of the plume at 40 miles depth up to the bottom of the 11,200-cubic mile magma reservoir, about 28 miles deep. The top of this newly discovered blob-shaped magma reservoir is about 12 miles deep, Huang says. The reservoir measures 30 miles northwest to southeast and 44 miles southwest to northeast. “Having this lower magma body resolved the missing link of how the plume connects to the magma chamber in the upper crust,” Lin says.

- The 2,500-cubic mile upper magma chamber sits beneath Yellowstone’s 40-by-25-mile caldera, or giant crater. Farrell says it is shaped like a gigantic frying pan about 3 to 9 miles beneath the surface, with a “handle” rising to the northeast. The chamber is about 19 miles from northwest to southeast and 55 miles southwest to northeast. The handle is the shallowest, long part of the chamber that extends 10 miles northeast of the caldera.

Scientists once thought the shallow magma chamber was 1,000 cubic miles. But at science meetings and in a published paper this past year, Farrell and Smith showed the chamber was 2.5 times bigger than once thought. That has not changed in the new study.

Discovery of the magma reservoir below the magma chamber solves a longstanding mystery: Why Yellowstone’s soil and geothermal features emit more carbon dioxide than can be explained by gases from the magma chamber, Huang says. Farrell says a deeper magma reservoir had been hypothesized because of the excess carbon dioxide, which comes from molten and partly molten rock.

A better, deeper look at Yellowstone

As with past studies that made images of Yellowstone’s volcanic plumbing, the new study used seismic imaging, which is somewhat like a medical CT scan but uses earthquake waves instead of X-rays to distinguish rock of various densities. Quake waves go faster through cold rock, and slower through hot and molten rock.

For the new study, Huang developed a technique to combine two kinds of seismic information: Data from local quakes detected in Utah, Idaho, the Teton Range and Yellowstone by the University of Utah Seismograph Stations and data from more distant quakes detected by the National Science Foundation-funded EarthScope array of seismometers, which was used to map the underground structure of the lower 48 states.

The Utah seismic network has closely spaced seismometers that are better at making images of the shallower crust beneath Yellowstone, while EarthScope’s seismometers are better at making images of deeper structures.

“It’s a technique combining local and distant earthquake data better to look at this lower crustal magma reservoir,” Huang says.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park