A new ecology study has posited a strong link between sanctioned hunting and poaching of endangered/threatened large carnivores.

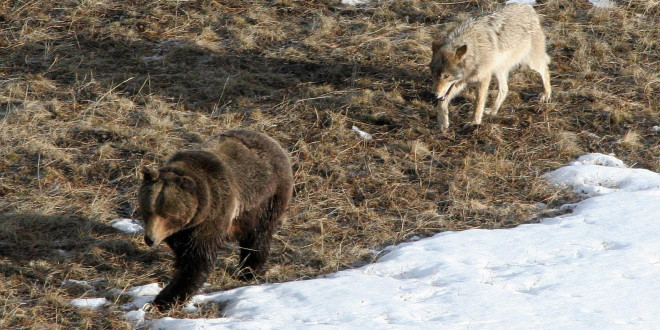

Written by Professors Guillaume Chapron (Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Riddarhyttan, Sweden) and Adrian Treves (Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin, 30A Science Hall, 550 North Park Street, Madison, WI, USA) and published by the Royal Society, the study analyzes the relationship between government mandated hunting (referred to as “culling” from here on out) of large carnivores such as wolves and bears.

Entitled “Blood does not buy goodwill: allowing culling increases poaching of a large carnivore,” the study analyzes management tactics of wildlife agencies in Wisconsin and Michigan between 1994 and 2012, specifically management of native wolf populations. The study also highlights management practices in Sweden, Minnesota, and other locales. You can read the full study here.

The study outlines the rationale of state wildlife agencies, to wit: “that liberalizing culling will reduce poaching and improve population status of an endangered carnivore.” In truth, Chapron and Treves, culling has the opposite effect, that poaching increased when culling was permitted—four times as much, on average.

Placing Value On The Individual

Chapron and Treves’ thesis, regarding the link between culling and poaching, is simple: people feel more inclined to poach a large carnivore when they see a government official do it too.

Further, while poaching may be illegal in such a management paradigm, since it’s not technically illegal to kill these large carnivores, as it would be, for instance, under the Endangered Species Act, individual wolves are devalued from a conservation standpoint. The act of hunting alone makes them more expendable. From Chapron and Treves:

When the government kills a protected species, the perceived value of each individual of that species may decline; so liberalizing wolf culling may have sent a negative message about the value of wolves or acceptability of poaching. Our results suggest that granting management flexibility for endangered species to address illegal behavior may instead promote such behaviour.

Indeed, the Center for Biological Diversity has specifically cited (and circulated) the study, saying that it undermines current notions of the efficacy/purpose of culling large carnivores in managed populations. From the Center for Biological Diversity:

“This paper disproves a convenient myth used to rationalize government persecution of wolves,” said Michael Robinson of the Center for Biological Diversity. “We hear over and over that individual wolves have to die in order to placate a wolf-hating public and prevent illegal killing — but this shows that to decrease poaching, the government should send the message that wolves have a high public value.”

[…]

This important study should trigger more humane, science-based management of wolves,” said Robinson.

Apples and Oranges?

Interestingly, the study does not mention Yellowstone wolves, which have been subject to several hunting seasons over the years. Rather, they cite the other large Yellowstone carnivore: the grizzly bear. Indeed, Chapron and Treves posit that wildlife managers seeking to delist Yellowstone grizzly bears while maintaining a “stable” population use the same flawed rationale as wolf managers in Wisconsin and Michigan.

You may be thinking that comparing wolf management to bear management is like comparing apples and oranges. The study, however, says otherwise; the two are comparable because both populations attract similar attention as large carnivores. From Chapron and Treves (note: this excerpt includes endnotes, indicated here in brackets, which we have included at the bottom of this article):

In 2007, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) proposed removing federal protections (delisting) for Yellowstone grizzly bears by claiming that ‘a future hunting season also may increase tolerance and local acceptance of grizzly bears and reduce poaching in the GYA’ [20]. It, however, later acknowledged in the final rule that ‘there is no scientific literature documenting that delisting would or could build … tolerance for grizzly bears’ but nevertheless maintained that ‘effective nuisance bear management benefits the conservation of the Yellowstone grizzly bear population by … minimizing illegal killing of bears’ [21]. Despite no additional scientific evidence being produced, the USFWS makes the same claims in 2016 in its new proposed rule to delist the Yellowstone grizzly bear [22] and argues that ‘while lethal to the individual grizzly bears involved, these removals promote conservation of the GYE grizzly bear population by minimizing illegal killing of bears and promoting tolerance of grizzly bears’. Similar claims have been made in court for legalizing wolf culling.

This proposition echoes wildlife biologist David Mattson’s opposition to delisting Yellowstone grizzlies. Indeed, Mattson feels the USFWS has based their delisting proposal off “cherry-picked data,” all the while ignoring the lives of individual bears and their context in the GYE.

Getting back to wolves, more broadly speaking, it may seem like apples and oranges comparing Yellowstone wolves to Wisconsin/Michigan wolves, but beyond geography there’s hardly anything separating these populations.

Indeed, considered alongside a study published earlier this year by the University of Washington, which analyzed the link between sanctioned hunting and wolf sightings in both Yellowstone and Denali National Parks, the Chapron/Treves study illuminates another facet of wolf management by state/federal wildlife agencies. Where Chapron/Treves see poaching rise with culling, the UW study finds the inverse: a rise in hunting sees a decline in wolf sightings.

—-

Endnotes:

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.