E.C. Waters wore many hats in Yellowstone over the years—hotelier, zookeeper, boat manager and, depending on who you asked, scoundrel.

Even in his heyday in the Park, Waters was never a sympathetic character. Many believe he went out of his way to shortchange you. A perpetual snub to authority in the Park’s early days, especially the Army, he managed to get on everyone’s bad side, according to Mike Stark, writing in the prologue to his superb history Wrecked In Yellowstone: Greed, Obsession, and the Untold Story of Yellowstone’s Most Infamous Shipwreck:

For those who had to work with Waters in those early days at Yellowstone—especially the army officers charged with maintaining order and overseeing the pleasures of thousands of powerfully well-connected visitors a year—he was a steady irritation and sometimes, because of his political connections, a threat to their careers. He forced one superintendent to be driven out of Yellowstone and tried to frame another to get him fired. His boating customers complained about his shady business practices—overcharging some and sending others onto the lake in creaky, leaky rowboats—while hotel companies complained that he stole their help, bad-mouthed their businesses, and ruthlessly irritated their customers. Still others were sickened by the make-shift zoo he kept on an island where captive elk and bison ate garbage. Over the years, the paper files on Waters at the park’s headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs bulged with complaints, recriminations, unctuous denials, paranoid rants, schemes, investigations, reports and bitter, bad feelings. Waters, one disgusted superintendent said, “had been the source of almost every complaint” in the park.

The man himself, however, was always certain in his victimhood.

Stark paints the picture of a man who believed he was due everything he worked for—money, prestige, protection, and respect—and whatever else you had left over, who was born into a hard life and sought whatever escape possible. And while he had little to no respect for the Army in Yellowstone, he had manifest pride about his service during the Civil War as “an unusually brave and faithful soldier;” he was 14 years old at time. When he died August 18, 1926, he was buried “with a delegation from the local Grand Army of the Republic attending.”

Although Waters was banned from the Park over his new boat, he was really guilty of a number of offenses, the most shocking of which was his aforementioned “zoo” on Dot Island. But there’s a pair of earlier offenses that, by all rights, should have led to his expulsion 20 years sooner.

In 1888, while showing off the Upper Geyser Basin to representatives from Northern Pacific, Waters “soaped” Beehive to make it erupt on command—a practice strictly forbidden by the Army, since it disrupts a geyser’s natural cycle—and was summarily arrested. Thomas Oakes, vice president of Northern Pacific, was arrested too, souring his and Waters’ relationship.

Shortly afterward, Waters ticked off Captain Moses Harris, the Park’s first military superintendent, by defending a pair of men who attempted to beat up, and later shoot, a surgeon living in the National Hotel. It was not the first time Waters had angered Harris, and Harris’ antipathy was passed onto all subsequent superintendents who had dealings with him.

The beauty of Wrecked In Yellowstone is how Stark treats his central subject. Whatever his personal opinion, Stark lets others malign Waters with their own words. And he lets others praise him. In spite of his posthumous reputation, Waters was, for a time, well liked. Indeed, before arriving in Yellowstone, he was a respected Billings hotelier and member of the Montana Territorial Legislature. Of course, by the end of his time in the Park, he was, as it were, “wrecked.”

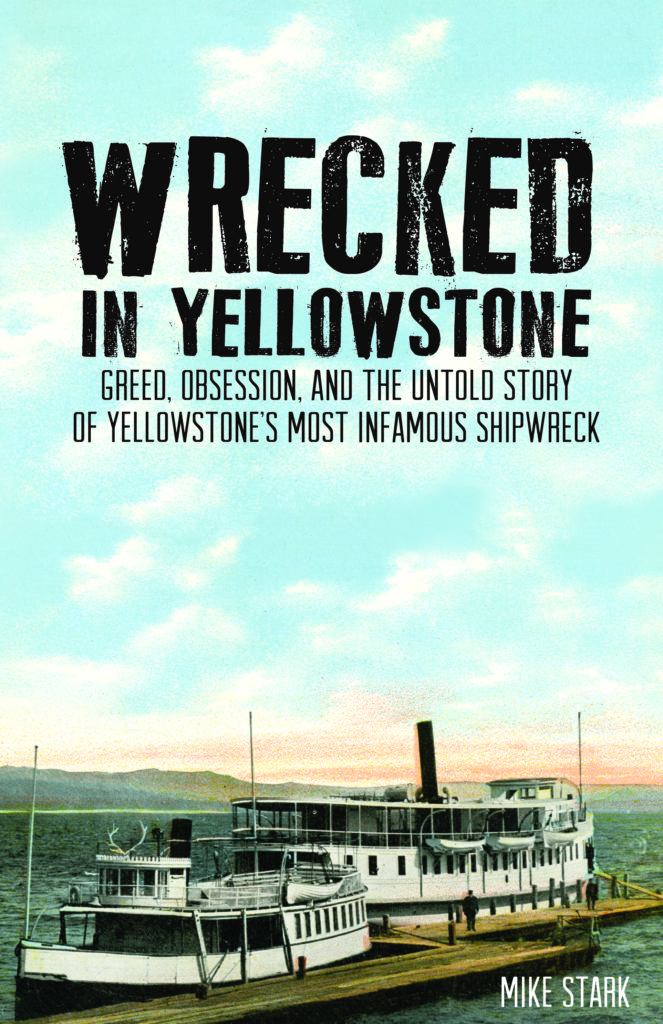

Speaking of which, there’s another subject Stark touches upon in Wrecked In Yellowstone, of course—the wreckage of his last venture, the steamboat E.C. Waters, “assembled piece by piece on the shores of Yellowstone Lake.” Poised to be his crowning achievement and the guarantee of his legacy in Yellowstone National Park, the boat soon became the leverage needed to oust Waters, as officials denied him an operating permit, forcing him to moor the boat near Stevenson Island.

By a series of misadventures (including the death of Waters’ proposed winter caretaker for the vessel, who suffered a heart attack rowing over to Stevenson Island) the boat sunk into the sand and became a proper wreck. It later served as a warming hut for adventurous skiers, a fish-fry restaurant, and a shelter for people looking to drink hooch and skirmish. Park managers even cannibalized the vessel, appropriating its boiler for use in the Lake Hotel in 1926.

The fateful moment for the wreck came in 1931 when a set of rangers set out to “remove” the wreckage once and for all—by burning it with flamethrowers. Suffice to say, it didn’t work, as you can still see the wreck of the E.C. Waters today (like in the above photo, taken in 1994 by Jim Peaco).

Of course, there’s more to the story, and if you want to know it, Stark is a very helpful guide, telling the story early Park managers hoped people would forget.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.