The Devil’s Slide might sound like a chief attraction for an amusement park; perhaps it’s a rollicking roller coaster or an impressively large log flume.

In actuality, the Devil’s Slide isn’t found behind any theme park fences, nor do you need a ticket of admission to see it. All you have to do is drive out to Cinnabar Mountain near Gardiner and Corwin Springs, MT and (of course) Yellowstone National Park. There you will see the Slide, curving down the slope, a gargantuan rock formation, whose beauty is enhanced by a florid streak of red winding on the face of the mountain.

Presumably, the feature had been noted long before the great survey expeditions arrived, but the Devil’s Slide did not obtain its name until the 1870 Washburn Expedition.

The Devil’s Slide is notable for two facets: its imposing ridges and (adjacent to the right ridge) a long streak of red rock. The streak draws attention by dint of its hue; it helped name both Cinnabar Mountain and the short-lived community of Cinnabar, MT that sat a few miles outside Gardiner. According to George Black in Empire of Shadows, “The curious rock formation … was first known as Red Streak Mountain but would later be called the Devil’s Slide” (47).

Of course, that red streak is not cinnabar, and the Devil’s Slide was (obviously) not made by or for the Devil. Rather, it’s the product of uplift and tilting; once exposed, the rock eroded at different rates, creating the distinguishing ridges seen today.

According to Black, describing the surveying habits of Lieutenant Gustavus C. Doane (one of the three pivotal figures of the Washburn expedition) the Devil’s Slide prompted great curiosity but did not inspire close inspection:

There were all sorts of new geological features for Doane to catalogue along the way, from the outcrops of ancient granite in the [Yankee Jim] canyon itself—Precambrian rocks that are some of the oldest in North America—to a vertical red stratum of Mesozoic sedimentary rock, exposed by the erosion of softer material, that he wrongly supposed to be cinnabar. Surprisingly they did not stop to take a close look at this striking phenomenon, but they gave it a name that is still used today: the Devil’s Slide (290).

Although the feature was named on the Washburn expedition, it gained more formal fame when Langford waxed eloquently about it (along with Yellowstone’s many other marvels) for Scribner’s Monthly in a multi-part article entitled “The Wonders of the Yellowstone.”

“We had seen many of the capricious works wrought by erosion upon the friable rocks of Montana, but never before upon so majestic a scale,” Langford wrote in his famed article. “Here an entire mountainside, by wind and water, had been removed, leaving as the evidences of their protracted toil these vertical projections, which, but for their immensity, might as readily be mistaken for works of art as of nature.”

Langford’s attempts at prophecy fell short for Devil’s Slide, when he asserted, “when the wonders of the Yellowstone are incorporated into the family of fashionable resorts, there will be few of its attractions surpassing in interest this marvelous freak of the elements.” Indeed, as marvelous a specimen of geology the Devil’s Slide is, it is a foreigner to Yellowstone, lying outside its boundaries.

In his “Wonders of The Yellowstone” article, Langford expressed reluctance at the choice of name: “For some reason, best understood by himself, one of our companions gave to these rocks the name of the ‘Devil’s Slide.’” He would go on to bemoan other features that invoked “his Satanic Majesty, or of his dominion, in signification of the varied marvels we met with.” He chalked it up to recalcitrance against one’s devout elders:

Some little excuse may be found for this in the fact that he old mountaineers and trappers who preceded us had been peculiarly lavish in the use of the infernal vocabulary. Every river and glen and mountain had suggested to their imaginations some fancied resemblance to portions of a region which their pious grandmothers had warned them to avoid.

There is no indication as to what he would have named the feature. Indeed, in his Washburn expedition diary, published in 1878, Langford hardly devotes a line to the feature: “We passed to-day a singular formation which we named ‘The Devil’s Slide’” (14). You will note Langford’s lack of righteous indignation at the naming, compared to the stump speech made in Scribner’s Monthly. Perhaps he didn’t have one “Satanic Majesty” in mind but a more run of the mill devil.

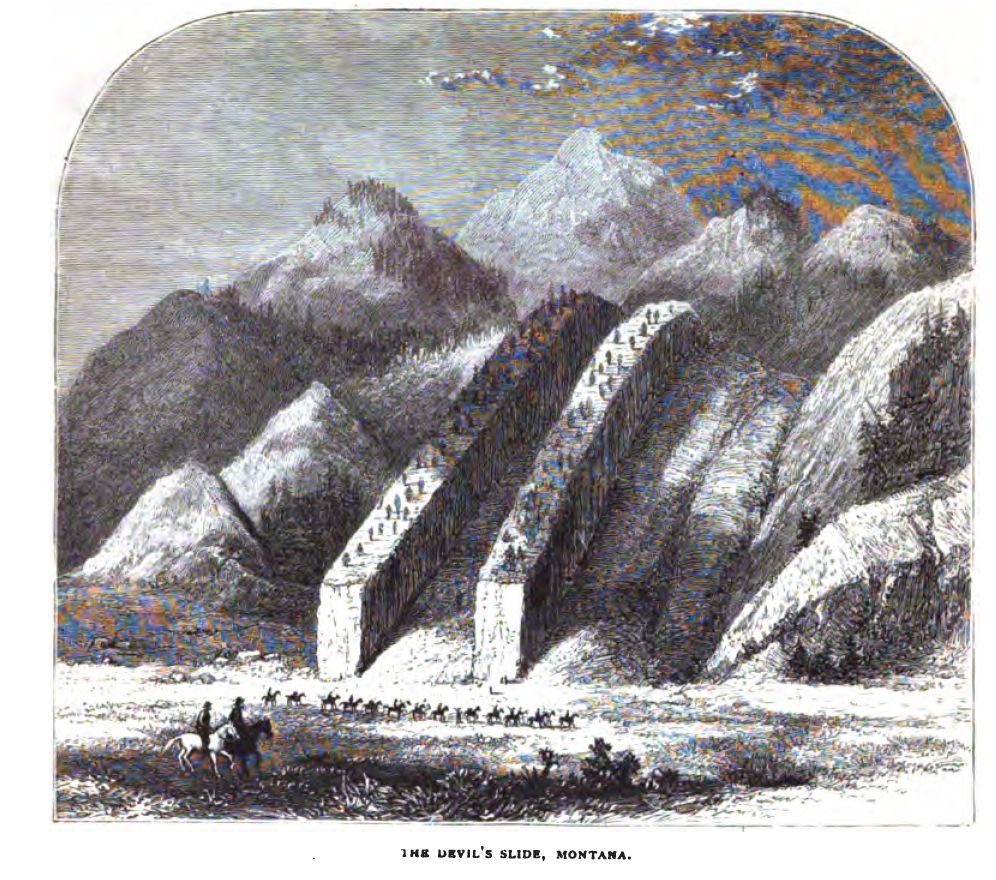

Curiously, the article included artwork by Scribner’s chief illustrator, one Thomas Moran, who would later gain fame as one of the principal artists of the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey. Without the benefit of having the feature in front of him, however, his rendition of the Devil’s Slide for Scribner’s (pictured above) is comically artificial, the geologic ridges more like sturdy fortress walls. He would go on to see the Devil’s Slide in person and sketch it (as shown below). Seen one after the other, they make for a curious juxtaposition.

Curiously, the article included artwork by Scribner’s chief illustrator, one Thomas Moran, who would later gain fame as one of the principal artists of the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey. Without the benefit of having the feature in front of him, however, his rendition of the Devil’s Slide for Scribner’s (pictured above) is comically artificial, the geologic ridges more like sturdy fortress walls. He would go on to see the Devil’s Slide in person and sketch it (as shown below). Seen one after the other, they make for a curious juxtaposition.

Formations such as the Devil’s Slide found outside Yellowstone are not unprecedented. Indeed, there is a famous Devil’s Slide located in Utah. Members of the 1871 Hayden Geological Survey saw said feature in person. George Allen wrote of Utah’s slide in one of his journals, quoted here from Marlene Deahl Merrill’s Yellowstone and the Great West. Page numbers are Merrill’s:

It is nothing more nor less than two parallel strata of metamorphic rock, several feet in thickness each, and separated from each other by a somewhat greater interval, which rises up from the general surface in two nearly vertical walls with even, clean-cut slides. The height of these walls varies in different positions from 20 to 40 feet. Commencing at the foot they stretch far up the mountainside all the way holding a perfect parallelism both in regard to comparative height and the interval that separates them, The upper or terminal edge of these walls is more or less irregular and jagged, while the sides are comparatively smooth. The space enclosed between these walls is dark and dismally suggestive. Such is the Devil’s Slide of Utah (52).

One of the privileges enjoyed by the Hayden Expedition, it seems, was being able to see both Devil’s Slides and thus be able to compare them (as it were) side-by-side. From the journal of Albert C. Peale, also quoted in Merrill’s compendium, using Merrill’s page numbers:

Proceeding a little farther, passing huge towering masses of stratified limestones, we came to Cinnabar Mountain, so called from the color or some of the rocks. Here we came to Devil’s Slide. This grand piece of nature is composed of two ridges of rock, one of igneous rock, the other of quartzite, each about 30-50 feet in width and both 200 feet in height. They are separated about 150 feet, {the rock between having been washed away in the lapse of time through the action of the weather. Standing in the gorge and glancing upward along the solid perpendicular wall, a feeling of aw comes over one, and our minds naturally revert to the time when these masses must have been forced into their present place.} On each side, at intervals, there are the remains of similar projections. In the centre of the first space to the left, running from the top to the bottom and distinctly outlines, was a broad red streak about 20 feet in width. These dykes must have been thrust up when the strata above were in position. That there was a terrible confusion here at some time in the past is proved a little further along, where the strata has been so twisted as to lie in three different directions {in a space of 200 feet} (126-27).

In addition to this textual rendering and Moran’s sketch, the Devil’s Slide was also captured in a photograph by William Henry Jackson, seen below. You can see up close how grand the Slide really is, although (alas) the red streak is less apparent. Nonetheless, it is striking.

The Devil’s Slide, from the Washburn expedition onward, has instilled awe and admiration in those who see it. Although it does not lie within Yellowstone itself, it is undoubtedly a scenic highlight for anyone who does see it, whether traveling to the Park or otherwise.

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

Yellowstone Insider Your Complete Guide to America's First National Park

You must be logged in to post a comment.